|

Abstract

The arrival of Europeans in

the Caribbean brought about irreversible demographic change.

Decimated by defeat and disease, ‘peaceful’ Arawaks and

‘warlike’ Caribs alike ceased to exist as an identifiable

ethnic group, their gene pool dissolving into that of the

newcomers, where it died away or remained un-investigated.

The replacement of native peoples by European settlers was

desultory. After their arrival in 1492 the Spanish explored

and settled the Caribbean islands with some enthusiasm. The

extension of activities into Mexico and Peru, however, rich

in precious metals and with a structured agricultural work

force, swiftly eclipsed the islands as a destination for

settlers. More northerly Europeans (French, English, Irish,

and Dutch) arriving later, slipped into the more neglected

Spanish possessions in the Leeward Islands (today’s eastern

Caribbean) or Surinam, on the periphery of Portuguese

Brazil. These seventeenth-century colonists initiated the

process which turned the Caribbean into the world’s sugar

bowl. To do so, they imported enslaved Africans who soon

became the most numerous group on the islands. In the

nineteenth century, as sugar receded in economic importance,

so too did the remaining whites, and the Caribbean assumed

its present Afro-Caribbean aspect.

|

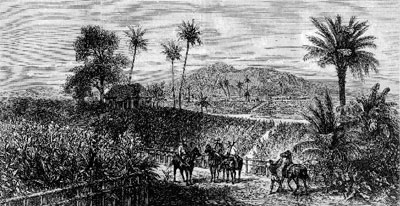

Tobacco plantations in Cuba

(Harper's Weekly, 12 April 1869) |

Changing the islands’

flora, fauna and demography, the newcomers also imported

their religious and political systems and ‘great power’

rivalries. Those who founded the colonies were eager for

royal support and recognition, thinking very much in terms

of subsequently returning home to enjoy wealth and

importance. As their tropical possessions proved themselves

valuable, kings and governments became more and more

determined to retain and expand them. The sugar boom made

the Caribbean a cockpit for warfare among the European

powers. This presented difficulties and opportunities for

the Irish. Divided at home into colonists and colonised,

when seeking their fortunes in Europe’s overseas empire,

they had to choose which king to serve, which colony to

plant.

|

|

Pioneer Settlers: The Case of Peter Sweetman

This

situation in the Caribbean was first clearly articulated

by Peter Sweetman in 1641. Sweetman had left Ireland with

the intention of becoming a substantial planter. His

chosen destination was Saint Christopher (Saint Kitts),

the first island where Europeans made a serious attempt to

develop tobacco plantations. Arriving simultaneously in

the mid-1620s, the English and French, fearful both of

native Caribs and Spanish claims to possession,

partitioned the island amongst themselves. Sweetman, a

subject of the British King Charles I and building upon

connections with English traders and adventurers who used

Cork and Kinsale as the last landfall on the Atlantic

crossing, led his entourage (male and female, soldiers and

servants) to the English sector of the island.

The

outbreak of the 1641 rebellion by Catholics in Ireland

against English rule caused Sweetman to rethink his

position. Tensions ran high between the English and Irish

colonists and the governor sought to defuse the situation

by deporting the Irish to the nearby island of Montserrat.

Uneasy about this move, Sweetman wrote to King John of

Portugal citing religious harassment and requesting to be

allowed to lead four hundred Irish from Saint Christopher

to an island site at the mouth of the Amazon. There,

Sweetman hoped to establish a distinct Irish colony,

promising King John that his group of soldiers and

servants, which included fifty or sixty married men, would

be a guarantee of security, stability and future

development.

The idea of

establishing an Irish tobacco colony along the Amazon

under an Iberian monarch had been put before the King of

Spain some years earlier. Church and King were well

disposed to such a proposal having already welcomed the

Irish as persecuted Catholics and useful soldiers.

Hispanic colonists in the Americas reacted differently,

seeing the Irish as northern intruders, pointing out that

not all of them were Catholics, complaining that wherever

they came they brought the English with them. The

Portuguese authorities now reflected a similar split. King

John therefore designed a compromise solution. He refused

Sweetman’s request for a distinct Irish colony, based on

the strategically placed island the Irishman had chosen.

Instead King John offered a mainland site where Sweetman

could establish a town. There he could be governor but the

head magistrate would be Portuguese. The Irish must become

naturalised Portuguese, admit other Portuguese subjects to

settle among them and accept the Portuguese judicial

system. They would also have to observe Portuguese trading

rules, which meant that they had to rely on merchants in

Lisbon (Lorimer 1989: 446-559).

Sweetman’s

hopes were dashed. He had hoped to set up a distinct Irish

colony in an island location where he could maintain

valuable trading connections with the English and the

Dutch, currently the best suppliers of capital, cheap

freight charges, manufactured goods, and African slaves.

So Sweetman’s attempt failed and the Irish were moved to

Montserrat. By 1667 a visiting British governor described

it as ‘almost an Irish colony’.

A decade

later a census of the island proved this description

correct, showing some sixty-nine percent of the white male

population and some seventy percent of the white females

to be Irish. On Nevis and Antigua, the Irish totalled

around a quarter of the white population; on Saint

Christopher they hovered around ten percent.

Neither the

Spanish Habsburgs nor the British Stuarts were prepared to

sanction an official Irish colony in the Caribbean. The

Irish therefore were left in the position of trying to

secure their advantage by playing off the rival powers

against one another. As France replaced Spain as the

leading Catholic power in Europe, Caribbean colonies moved

from tobacco to more valuable and capital-intensive sugar

cultivation. The division of Saint Christopher into French

and British sectors thus became more politically volatile.

The Irish

could prove politically influential. In 1666, when Britain

and France declared war, it was the Irish who ensured the

triumph of the French on Saint Christopher and Montserrat.

An English colonist commented that ‘the Irish in the rear,

always a bloody and perfidious people in the English

Protestant interest, fired volleys into the front and

killed more than the enemy of our own forces’. Montserrat,

as well as the entirety of Saint Christopher, passed into

French control, a situation reversed a year later. The

English took over, demoting Montserrat’s Irish Protestant

governor for helping the French, and installing William

Stapleton, an Irish Catholic, in his place, as he

understood ‘the better to govern his countrymen’ (Akenson

1997:55-58).

It was the needy nobles of Portugal and

Spain who established Europe’s first overseas empires.

Landless younger sons, fidalgos and

hidalgos,

bred to avoid manual labour and give orders to their

social inferiors, took to soldiering, eager to conquer and

discover new lands. In doing so they frequently encouraged

the family’s peasantry to leave the fields, take up arms

and stagger on shipboard. Peter Sweetman, setting off for

Saint Christopher with his armed retinue and bond

servants, was an Irish version of this European

phenomenon. |