|

Introduction

On

the recommendation of Whig contacts in the anti-slavery

movement, including William Wilberforce’s successor, Thomas

Fowell Buxton, Madden was among the first Irish Catholics

appointed, after the 1829 Act removed barriers to the

employment of Catholics in the British public service.

[1] Although he had no legal background,

as a medical practitioner, Madden had witnessed slavery

in the Middle East under the Ottoman Empire, making him

uniquely qualified for what would become the first in

a series of dangerous human rights missions. A native

of Dublin with a thriving medical practice in London’s

fashionable Mayfair, Madden abandoned his career as a

physician to devote himself full-time to the anti-slavery

cause. In October 1833, accompanied by his English wife,

Harriet, he boarded the Eclipse at Falmouth and

set sail for the British West Indies.

|

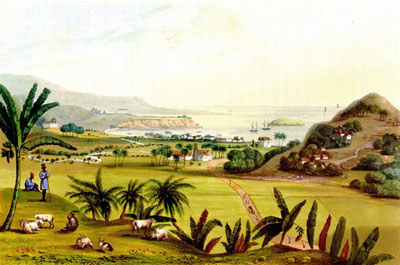

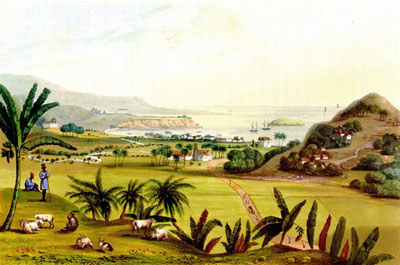

A

painting of Jamaica representing what the island

looked like when Madden, and the other five

Special Magistrates, landed there in November

1833; their arrival provoked intense hostility

from planters.

|

Madden

was one of six Special Magistrates who landed in Jamaica in November 1833, where their arrival provoked

intense hostility from planters. No sooner had the select

band set foot on the island than they experienced rumblings

underground, described by Madden as ‘a harbinger which

was considered an appropriate introduction for persons

with our appointments’ (Madden 1835: 80). These earth

tremors did indeed foreshadow the effect the newcomers’

mission had on the island’s status quo.

Any

expectations they might have entertained regarding the

reception awaiting them were shattered by the headlines

in the local newspapers. According to one editorial, the

Secretary of State, Lord Stanley, had sent a crowd of

‘sly, slippery priests from Ireland’ to support themselves

on the poor colonists. The press embellished their reports

with a biblical reference labelling them as ‘strangers,

plunderers, and political locusts’. Interference on the

part of these newcomers was disrupting the peace of the

island by promoting ‘disorder and confusion’ with their

‘insidious practices and dangerous doctrines’ (Madden

1835: 33).

Among the enslaved population, however, the reaction was

altogether different. From their perspective, the magistrates

were sent to the island as saviours who would deliver

them from bondage. There was a palpable sense of excitement,

as everyone eagerly anticipated Emancipation Day, set

for ‘the 1st of August’ of the following year.

Losing

no time, Madden was officially sworn in as Special Magistrate

by Lord Mulgrave and settled into his duties in St. Andrew’s

parish, an area of approximately 455 square kilometres

just north of Kingston.

[2] From there

he transferred to the City of Kingston, the island’s commercial

and administrative centre, when this important region

was placed under his jurisdiction.

|

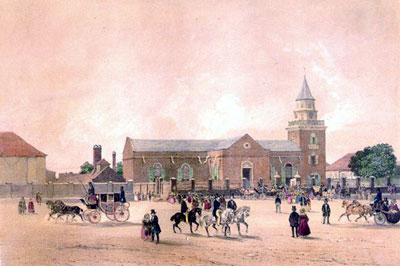

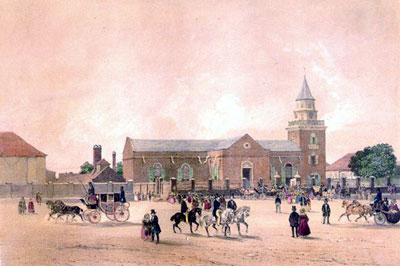

A

painting of the city of Kingston

around 1833.

Kingston

was

Jamaica’s commercial and administrative centre where

Madden was officially sworn in as Special

Magistrate by Lord Mulgrave.

|

Madden’s tenure was marked by illness, controversy, and

violence. Within nine months of their arrival, yellow

fever and other tropical diseases caused the untimely

demise of four of the special magistrates who had accompanied

Madden on the Eclipse. Evidently, the Irishman’s

medical training and standards of hygiene inoculated him

from the ravages of disease as he adapted to the unfamiliar

climate.

On

what he later described as the proudest day of his life

(Madden 1891), Madden was present for the historic Emancipation

Day Proclamation, delivered by Lord Mulgrave, in Spanish

Town, Jamaica, on 1 August 1834. Far from disturbing the

peace of the island as the authorities had feared, slaves

celebrated the occasion with church services and ‘a quiet

and grateful piety.’

[3] According to

the provisions of the Emancipation Act, by way of compensation,

the government had earmarked £20 million (more than

£800 million in today’s currency) to be paid to

former slave owners for loss of ‘property’. Slaves younger

than six years of age were to be freed, while those six

years and older were required to serve a term of apprenticeship

designed to teach them how to behave in freedom, or, as

the Act stipulated, ‘to accustom themselves, under appropriate

restraints, to the responsibilities of the new status’

(Temperley 1972: xi). Under threat of corporal punishment,

house slaves were required to serve a period of four years;

praedial slaves had to serve a period of six years, in

what amounted to little more than a system of modified

slavery.

During

one of his numerous trips around the island, Madden set

out for St. Mary’s Parish to find the location of a small

plantation property known as Marley that had

once belonged to a distant relative long since deceased.

At the end of an exhausting day’s ride in the verdant

mountains, whose heavily wooded areas and limestone soil

had sustained countless runaway slaves, he discovered

what appeared to be the abandoned remains of the old Marley

plantation. Making his way along the narrow, mostly overgrown

path, he encountered three women, former slaves, who had

been living in the dilapidated old house for many years.

To his astonishment, the two younger, middle-aged women

turned out to be the daughters of Madden’s great-uncle,

Theodosius Lyons, the previous plantation owner. He could

even see a strong family resemblance, and the elderly

woman was their mother. As the story unfolded, the sisters

described how, following the sudden death of the plantation

manager, their younger brother was sold to pay off the

debts of the estate.

|