|

As

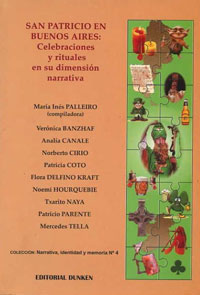

an original collection of essays dedicated to the analysis of

St. Patrick's Day in present-day Buenos Aires from a general

perspective of socio-cultural anthropology, San

Patricio en Buenos Aires is a significant book which is

likely to become a reference work for further studies in this

field.

Furthermore,

this book represents an excellent starting point in this

direction, including an array of articles and a 'multiplicity

of converging, diverging, and juxtaposing viewpoints about the

figure of St. Patrick and the Celtic world to which he is

traditionally linked' (13). These perspectives include and

follow shared principles like the 'artistic performance, the

expressive form, and the aesthetic and cognitive response that

draw on traditions rooted on social contexts' (13).

This

is the fourth volume of the Narrative,

Identity and Memory collection, and it is dedicated to

'the study of different discursive modes of memory building,

with a particular focus on the narratives understood both as

discourse mode and cognitive instrument for experience

articulation (Bruner 2003)' (11).

Ethnic

and Religious Celebrations

In

order to contextualise this review, it is necessary to explore

a brief history of St. Patrick's Day celebrations in Buenos

Aires

According

to Thomas Murray, the first recorded St. Patrick's Day

celebration in Buenos Aires was in 1843, and it 'took the form

of a dance at Walsh's Tea Garden, [1]

which lasted all night and was attended by some one hundred

merry-makers' (Murray 1919: 125). However, the author

recognises that the function of that year was not the first of

its kind in Buenos Aires. Maxine Hanon came across the first

news about this celebration in the British

Packet newspaper as early as in March 1829: 'St. Patrick's

day on the 17th. inst., was duly commemorated by various

private individuals of this city, natives of Erin's Isle,

although no public entertainment took place. The flag of old

Ireland floated from the top of Mr. Willis's Naval Hotel

(Irish Jemmy's) [2] and its

occupants seemed to have no other thought but to honor the

day' (Hanon 2005: 70). The fact that Irish

Jemmy was Protestant and his guests were indistinctly

Catholic or Protestant suggests that the common Irish origin

of the people celebrating St. Patrick's Day in that early

period was more important than their religious

background.

In

1830, the British Packet

commented that St. Patrick's Day 'did not go off so dryly as

last year. […] Captain O'Brien, of the Chili brig

Merceditas, in the inner roads, displayed the flag of that

republic from his vessel; and there were several private

parties, in which every honour was paid to the sainted day'

(Hanon 2005: 70). In addition to Willis and Welsh, other

organisers of the Irish festivity at that time were Edmund

Kirk and Patrick Fleming. In 1833, Welsh had sixty guests in

his tea garden, and three other parties were organised by Kirk

and others. The British ship Iris,

captain Pagan, and the Argentine Domingo,

captain O'Brien, hoisted Irish flags and the paper commented:

'This year Saint Patrick cannot complain that his sons in

Buenos Ayres did not honour his [relics] and memory' (in Hanon

2005: 70, my translation).

In

1837, the celebration at Edmund Kirk's house was chaired by

the Irish priest Fr. McCartan, [3]

and drinks were offered in honour of William IV, Princess

Victoria - 'the hope of Ireland and the Empire' - Daniel

O'Connell, General Juan Manuel de Rosas, and others.

Addressing the public, Fr. McCartan praised Princess Victoria

as 'she is imbued with liberal sentiments; and upon the

prolongation of her life are fixed the hopes of peace, justice

and prosperity for your native land, and the tranquillity of

the Empire. […] The Government of His Excellency General

Rosas has been attended with the most beneficial results, that

is, it has produced public order, and given security to

property and life, where all had been heretofore anarchy,

confusion, and bloodshed. Such a marked change for the better

is exceedingly creditable to the head and heart of His

Excellency, whose health I have now the honour to give' (Hanon

2005: 70).

We

do not know the details of these celebrations. In 1839, there

were seventy people who dined, toasted, sang and danced up

'till Aurora, envious of the enjoyment of such much sublunary

pleasure, speeding the pace of her spirited steeds, came

forth' (Hanon 2005: 70). About thirty years later, when

reading a letter from John Pettit of Australia and formerly

from Buenos Aires, 'Mrs. Kirk […] told of the many St.

Patrick's day dinners they had had together and how when she

would speak of what they should have, he would say "never

mind old woman, give them plenty of fish and potatoes"'

(Sally Moore to John James Pettit, 25 October 1866, in Murray

2006: 94). The following year, on 17 March 1840, the

celebration went public when a band played God

Save the Queen through the streets of Buenos Aires

From

the mid-1840s, when Irish migration to Buenos Aires was

significant compared to migration from other countries,

nationalism became a frequent topic in the celebration of St.

Patrick's day. In 1844, Queen Victoria and Governor Rosas were

proposed in the toasts. However, there were also drinks in the

honour of 'Daniel O'Connell, Ireland's Liberator and the

Repeal of the Legislative Union between Great Britain and

Ireland', 'the principles proclaimed by the Volunteers of

1782', [4] 'Ireland for the Irish

and the Irish for Ireland', 'the U.S. of America - the

generous asylum of persecuted Irishmen', 'the sympathisers

with the wrongs of Ireland, in every part of the globe', and

'Admiral William Brown - he has proved himself by his

undaunted courage in a hundred combats, a true son of Erin'

(Hanon 2005: 71).

In

the second half of the nineteenth century, at the same time

that St. Patrick's Day marches were held in New York and other

locations of the Irish Diaspora, the festivity was also

celebrated in Carmen de Areco, San Andrés de Giles, Capilla

del Señor, Lobos, Venado Tuerto and other Irish settlements

of the provinces of Buenos Aires and Santa Fe. In addition to

the nationalist speeches and symbols, the religious character

of the celebration was emphasised by the Irish Catholic

chaplains, who from that time became the main organisers and

leaders of the Irish communities, at least in the rural areas.

Protestant elements were avoided and the Irish-Argentine press

focused on the connections between the saint and Catholic

Ireland. Sometimes the celebration coincided with the opening

of chapels in areas of Irish settlement, Killallen in Castilla

(1868), St. Brigid's in Rojas (1869), St. Patrick's in Capitán

Sarmiento (1870), Sts. Michael and Mel in San Patricio (1870),

the parish church of Venado Tuerto (1883),

and Las Saladas in Navarro (1898). On 17 March 1875,

many of the women attending the mass at the San Nicolás de

Bari church of Buenos Aires were 'displaying green ribbons and

feathers'. Later at the dinner in Hotel de la Paix, many men

wore 'green rosettes and shamrocks in their hats', and 'the

dining salon was most tastefully decorated: the green flag of

Erin, the flag of England and the Argentine flag were

gracefully hung at the head of the hall'. This was 'the first

time in twelve years that St. Patrick's Day in Buenos Aires

was celebrated in a befitting manner' (The

Southern Cross, week of 17 March 1875 in The

Southern Cross: Número del Centenario, pp. 9, 100).

It

was on Sunday, 17 March 1912, that the saint's day was

celebrated in Luján Basilica with a national gathering of

almost all of the Irish communities in Argentina. From that

time, whenever St. Patrick's Day falls on a Sunday, there is a

crowded reunion in Luján which is emblematic of the ethnic

and religious character of the festivity. 'On the 17th, St.

Patrick's day, Mrs. O'Loughlin, Julia, Laura, Lawrence and I

went to Luján for the pilgrimage. There was a great crowd

there' (Memoirs of Tom Garrahan in Murray 2005: 130).

The

celebration has evolved from a national reunion in the

nineteenth century to a religious festivity in the first half

of the twentieth century to a social gathering today.

From

National Festivity to Dionysian Merriment

As

well as the depth of its contents, San

Patricio en Buenos Aires stands out for its copious

bibliographical references and multi-disciplinary

perspectives. The different authors offer both synchronic and

diachronic angles of anthropology, sociology, literature,

'classic' history and history of religions, and linguistics.

The book is addressed to readers with a specialisation in the

above-mentioned fields, and it will be very useful for

students of socio-cultural anthropology and history. However,

the multidisciplinary approach offers a wide standpoint for

the general reader interested in understanding St. Patrick as

a Celtic symbol in the context of the Irish diaspora in

Argentina

The

introduction by María Inés Palleiro et

al. sets out the theoretical framework, examining links

with folklore and presenting different concepts. Among them

are the folkloric performance (23) and Derrida's arkhé

(25), as well as the recreation of traditions to support the

construction of new messages from historical paradigms.

Narratives are also positioned in a cognitive perspective, and

the contemplation of rites from a performative and artistic

point of view. Based on the Irish migration to Latin America,

and more precisely to Argentina, an analysis of the

commemoration of the bishop Patrick as patron saint of all the

Irish, including (or particularly) those living in the

diaspora. Both as a symbol of the Catholic church and as an

ethnic epitome, Patrick becomes a justification for the

identity re-building process of Irish emigrants. This process

is performed through the liturgy - including the exemplary

rhetoric and the inflexible structure - and at the same time

through its antithesis, Celtic festivals and street gatherings

with structural elements of medieval carnivals. Within the

global and marketing context in which the space-time continuum

stretches under the effects of the 'virtual Nation' (83), the

street party becomes increasingly significant and visible.

The

eight essays included in this volume focus on different

aspects of memory and identity, with their heterogeneous

approaches to performance through diverse discourses. The

first contribution, by M. I. Palleiro, presents a comparative

diachronic analysis of a medieval version of the European Purgatory of St. Patrick, and an oral version within the

contemporary Argentine context. The following article, by V.

A. Banzhaf, focuses on the development of Celtic and Christian

cultures, as well as the diffuse border between history and

myth in the various medieval versions of The

Purgatory of St. Patrick. P. H. Coto de Attilio analyses

the 'ideological context' of a personal history that

emphasises the individual and group subjectivity of memory and

identity. P. Parente studies the normative and exemplary

narratives in Christian hagiography through two fairytales. In

his article, N. E. Hourquebie covers the identity aspects of

images representing Celtic fairies in tattoos, within the

framework of social exclusion. The sixth essay, by N. P.

Cirio, examines the reinvention of Celtic music as a

ritualised practice, and its re-actualisation in the Argentine

contemporary context. F. Delfino Kraft's chapter is dedicated

to the two-fold discourse on alcohol consumption as a practice

linked both to the celebration of St. Patrick's Day, and to

exemplary Irish history, with reference to its negative

effects. The closing piece, by A. Canale, revises the

reinvention of tradition signifiers and of local identities in

Buenos Aires, together with the street celebrations of St.

Patrick's Day.

The

articles are exposed with a lucid approach and include

meticulous argumentation, in which the form corresponds to the

content and the well-developed internal logic is by and large

convincing. An excessive compulsion to present minor details

and to include a great quantity of references resulted in a

substantial work. However, this complexity may also be a

weakness since sometimes the text moves away from the main

objective. Therefore the introductory essay is occasionally

crammed with detailed explanations, as in the section 'La

celebración litúrgica del patrono de Irlanda en la

Argentina' (42-46). As a particular element of the

celebration, the mythic discourse (43) is indeed an important

feature, though it may be excessive to dedicate one page to

the contextual analysis of Eliade and Jackobson. The reader

may lose focus with information that is certainly interesting

but too specific for the book's objective. The same detail is

apparent in the following pages (51), where the etymology of enxemplo

is examined. This abundance of references and detail would be

better positioned within the context of more specific and

critical studies.

The

articles in this book are interesting, well documented and

reasoned, though on the other hand their heterogeneity begs

the question of what the connection is between them and the

object of the book as represented in the title. Particularly,

V. A. Banzhaf's 'El "Purgatorio de San Patricio" en

versiones medievales: los cruces de una tradición' (119-136)

is a good example of this. This essay is valuable and

well-structured from the perspective of comparative literature

of medieval texts. However, it is difficult to establish a

connection to the rituals and celebration of St. Patrick's Day

in present-day Buenos Aires. This is balanced by its accurate

placing after the comparative article of M. I. Palleiro, which

gives Banzhaf's piece a continuity and structural coherence

within the book. The subsequent essay, 'Una pequeña historia:

memoria e identidad en un relato personal' de P.H. Coto de

Attilio (137-150), raises the same sort of questions. The

analysis of certain healer practices - which would be better

situated in a book about medical anthropology - covers a field

study in the context of contemporary Argentina, but it is too

distant from Saint Patrick as a symbol and his commemoration.

Nevertheless,

the achievement of this multi-authored work is to reunite

heterogeneous reflections on a concrete subject. The editor

and the authors are to be congratulated for their

accomplishment within the framework of anthropological

research about the Irish Diaspora in Argentina. The problems

of identity and memory, as well as the diverse discursive and

performative expressions, are at the heart of Palleiro's

collection. As mentioned above, it is necessary to consider

her work as a point of departure for the multiple avenues of

analysis and knowledge improvement.

Irina

Ionita

* Institute of Development

Studies, University of Geneva

Translated

by Edmundo Murray

References

-

Hanon, Maxine. Diccionario

de Británicos en Buenos Aires (Primera Época) (Buenos

Aires: author's edition, 2005).

-

Howat, Jeremy. 'St John's Marriages, 1828 to 1832' in British

Settlers in Argentina: Studies in 19th and 20th Century

Emigration. Available online

(http://www.argbrit.org/),

accessed 25 November 2006.

-

Murray, Edmundo. Becoming

irlandés: Private Narratives of the Irish Emigration to

Argentina, 1844-1916 (Buenos Aires: L.O.L.A., 2006).

-

Murray, Thomas. The

Story of the Irish in Argentina (New York: P.J. Kenedy

& Sons, 1919).

Notes

[1]

Welsh [Walsh], Michael (ca.

1790-1847), mason, was born in Clonmel, County Tipperary. In

1819 Michael Welsh arrived in Buenos Aires with his wife

Cecilia, née

Bowers, and their daughters Brigid and Margaret. Welsh

specialised in chimneys and stoves, and worked on improvements

in the installations in saladeros (meat-curing plants), churches - like St. John's Anglican

cathedral - and private houses. He also worked in Montevideo

at different periods. His house in Viamonte and Cerrito was

the location selected for numerous St. Patrick's Day

celebrations and, in 1838 and 1841-1843 opened as a tea

garden. Michael Welsh died on 24 July 1847 in Montevideo

(Hanon 2005: 836).

[2]

Willis, James (b. ca.

1790), publican, was born in County Kilkenny, and arrived in

Buenos Aires in August 1816 with his son John Willis. By 1829,

he owned the public house and naval hotel known as Irish

Jemmy's, in the 25 de Mayo Street of Buenos Aires. He was one

of the founders of the British Hospital in 1844 (Hanon 2005:

862). On 4 August 1829, James Willis married Mary Quin of

Cork, Ireland, at the British Protestant Episcopal Chapel

(Jeremy Howat, St John's Marriages, 1828 to 1832).

[3]

The Catholic priest Michael McCartan (1798-1876) was born in

Belfast and entered Maynooth in 1817 to study for the

priesthood. He was ordained on 16 June 1821 by the Archbishop

of Dublin Dr. Daniel Murray. McCartan had some disagreement

with the bishop of Dromore, seemingly for political reasons.

He wrote letters to the press criticising the bishop, and was

banished to Nova Scotia. He travelled to England, North

America, the West Indies and Chile, and arrived in Argentina

in 1836. He was appointed parish priest in Concordia, Entre Ríos

Province, from where he was banished for extreme political

opinions. After that he ministered at San Roque Chapel of

Buenos Aires. He then left Argentina and travelled extensively

in South and North America, before returning to Argentina in

1862. He died on 23 June 1876 in Fr. Patrick Dillon's house

[Murray 1919: 98-100].

[4]

The Volunteers were an armed force in Ireland recruited in

1778-1779 originally to guard against invasion, but who soon

took on a wider political importance as an expression of

middle-class consciousness. The Volunteers supported the more

militant patriots, and their Convention at Dungannon of

February 1872 provided the starting point for the final,

successful drive for legislative independence (S. J. Connolly,

ed., The Oxford

Companion to Irish History, p. 581).

Author's Reply

This summary

managed to capture the fundamental aspects of our research

into St. Patrick’s Day in Buenos Aires from a synchronic and

diachronic perspective. We would like to emphasise that the

distinctive feature of this research was its placement within

a human resources training programme, dedicated to Training in

the Process of Folk Tradition Research (EPIF), based at the

Folk Tradition Section of the Anthropology Institute of the

University of Buenos Aires, headed by Ana María Dupey. I was

in charge of co-ordinating this programme under Ana María

Dupey’s supervision and with the valuable advice of Diarmuid Ó

Giolláin, of Cork University. In this inter-disciplinary

programme, young graduates and advanced students carried out a

general investigation, which had as its starting point a field

research ethnographic paper based on an initial theoretical

framework which I had established (Palleiro 2004) and

reformulated for the specific study of Ireland’s patron saint.

In this framework, the performance of social belonging in a

context, the communicative dimension and the aesthetic

elaboration of folk events were taken into account. In the

general research, Verónica Banzhaf worked on aspects relating

to medieval sources referring to the figure of the patron

saint of Ireland, between history and legend. Patricio Parente

surveyed and analysed the street celebrations in the urban

context of Buenos Aires, and I, with the help of Flora Delfino

Kraft and María del Rosario Naya in field research, analysed

aspects relating to the liturgical celebration. For her part,

Mercedes Tella focused on the analysis of the advertising and

marketing generated around the celebration and Flora Delfino

Kraft focused her interest on examining the debates

surrounding this celebration on the internet’s virtual fora.

On the basis

of this general research, those who took part in the programme

also developed individual articles, the thematic focal points

of which were highlighted with great incisiveness by the

author of the summary, and consulted with qualified

researchers and specialists in various issues linked to the

narrative construction of identity and memory, such as Analía

Canale, Norberto Pablo Cirio, Patricia Coto and Noemí

Hourquebie. These experts, using St. Patrick’s Day and Celtic

culture in Buenos Aires as a basis, contributed their research

on, respectively, the Buenos Aires’ carnival and murga,

[*]

Celtic music, the oral narratives of migrant communities and

the micro-narratives of body tattoos.

Diarmuid

Ó Giolláin’s prologue deserves special mention and highlights

the two-fold local and global dimension of St. Patrick’s Day,

which functions both as an emblem of identity configuration

for the Irish community and as a symbol of its opening to a

transnational dimension which includes, in his own words, ‘the

Boston police band as much as the Killarney boy scouts and the

revellers in Retiro.’

Ana María

Dupey’s incisive preliminary commentary is also worth

highlighting as it stresses the framework of our work on St.

Patrick’s Day in Buenos Aires within an opening up of the

disciplinary field of folk studies to diverse aspects and

manifestations.

It is also

worth giving special mention to the reading made by Alejandro

Frigerio, expert researcher in ritual anthropology, who, at

the paper’s presentation, linked our research on St. Patrick

in Buenos Aires with issues such as the celebration of St.

Patrick associated with the cult of the orixás in

Afro-Brazilian culture.

A large part

of these aspects were identified and highlighted with great

incisiveness by the author of the summary, who we thank for

her careful reading of our paper and her pertinent framework

within studies on Irish migration, paying special attention to

the excellent work of Edmundo Murray, whose legitimisation of

our paper is of great importance for our research group in

Argentina.

The warm

support of the Irish community in Argentina deserves our

gratitude, particularly that of Kevin Farrell, President of

the Federation of Irish Associations in Argentina, of Teresa

Deane Reddy from the Irish newspaper The Southern Cross,

of the priests Eugenio Lynch, Thomas O`Donnell, Ambrosio

Geoghegan, Pablo Bocca and Carlos Cravea, and of Maradei de

Morello, from San Antonio de Areco, who gave us the initial

contacts to begin our work in that area.

All of these

contributions resulted in our paper, with its framework of

studies on Irish culture at international level, thanks to the

authors and editors of this summary, who contributed valuable

observations based on personal experience and knowledge,

allowing us to redefine not only the paper but also the new

research we are carrying out, focusing on the theme of belief.

María

Inés Palleiro

Translated by

Annette Leahy

[*] A

form of popular musical street theatre performed during

carnival. |