|

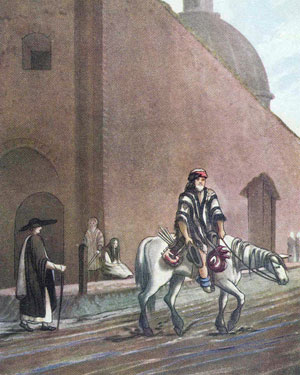

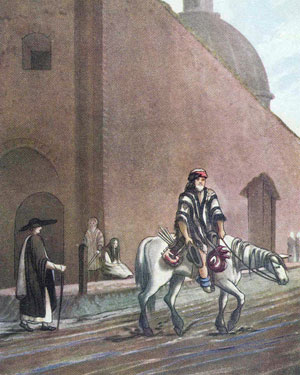

Beggar on horseback

(Emeric Essex Vidal, 1820) |

This aspect of the life in the Pampas

levelled the whole population, rendering them a uniform

horse-riding people, a fact that was amazing in the eyes

of English and Irish visitors, accustomed to the familiar

figure of landlords - and sometimes large farmers, but

rarely peasants or labourers - on horseback. Moreover, in

Buenos Aires ‘the mounted beggar stands at the corner of

the street, and asks charity; his horse is no more proof

of his being undeserving of alms than the trowsers [sic]

of the English mendicant’ (Caldcleugh 1825: I, 172).

‘[H]is manner is essentially different from that of the

real object of charity. He accosts you with assurance and

a roguish smile; jokes on the leanness of his horse,

which, he says, is too old to walk; hopes for your

compassion, and wishes you may live a thousand years

(Essex Vidal 1820: 52). Rather than social scandal, these

views excited the imaginations of the Irish immigrants

and, particularly, of their fellow countrymen and women at

home. If anyone (even beggars) in the Pampas could own a

horse, by analogy the dream of land ownership could be

realised, and upward social mobility - becoming a

landowner - could become a reality for the industrious

young tenant farmers of Ireland.

Pato,

maroma, and cuadreras

From the early seventeenth century, following the fashion of

other Spanish and Portuguese colonies, bullfighting was

the most important social amusement among the people of

Buenos Aires, Montevideo and other locations in the Río de la Plata

region. Local versions of the corridas, in which

the torero kills a bull assisted by lancers on

horseback and flagmen, were developed. Wild bulls and cows

were mounted by expert riders (toreo a la

americana),

and complementary fights between teams of smart

horse-riders armed with canes were organised (juegos de

cañas). The latter game was eventually replaced by

pato (‘duck’), in which two, three or four teams of

several accomplished riders struggled for the possession

of a rawhide bag containing a live duck, and to carry it

to the big house of their own estancia. Among other

popular pastimes among gauchos on horseback were

pechadas, during which the players would violently

shove each other until the winner would be the only one

still on the mount, and maroma, which consisted of

jumping from a high gate or tree on to the back of a horse

galloping at full speed. [4]

Certainly the most popular entertainment in the Pampas

was horseracing. The local form, cuadreras, was

performed during holidays or on the day after a successful

round-up of wild cattle. The differences with British

races were observed and accounted for by Essex Vidal:

Horse-racing is a favourite diversion of the people of

Buenos Ayres, but it is so managed as to afford little

sport to an Englishman. There are no horses trained for

racing, nor is attention paid to the breed with a view to

that object. No match is ever made for more than half a

mile; but the ordinary distance is two quadras, or three

hundred yards, and the race is decided in a single heat.

To make amends for this, however, they will start more

than twenty times, and after running a few yards, return,

until the riders can agree that the start is equal

(Essex Vidal 1820: 113).

There were never more than two horses in the same race, and

the winner’s advantage must always be con luz

between the horses, that is, upon arrival there should

always be a distance between the first’s back and the

second’s nose. It was not allowed for racers to jostle the

adversaries off the course, but they could throw ‘one

another out of their seat, which is allowed, if it can be

accomplished; but with such expert riders it is extremely

difficult, and therefore seldom attempted’ (113). In ‘The

Defeat of Barragan’, William Bulfin tells of the intense

conclusion of a race between the hero Castro and the

villain Barragan, who

closes in

and tries to jostle as they race. Castro, holding the top

of his head against the whistling wind, turns his face

sideways and, looking into the face of his adversary,

while he raises his right hand, shouts, “I defy you to do

it.” The other, flogging with all his might, edges in. It

is an old dodge! He has done it scores of times before;

but to-day he has met his master. As the breast of his

horse touches Castro’s right leg, my companion [Castro]

lifts his whip, which in the meantime he has gripped by

the tail. Two swift strong cuts and he is free, […] amidst

the cheers of his hundreds of backers leaves the bayo

nowhere. Barragan […] is entirely beaten. Castro has the

rest of the running to himself, and crosses the line

twenty yards ahead of his rival

(Bulfin

1997: 94). |