|

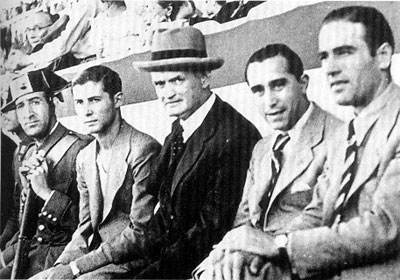

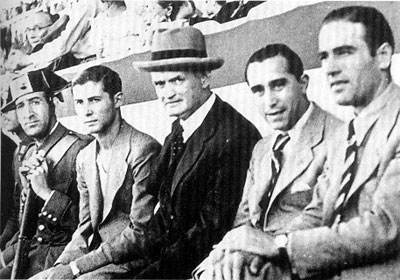

Patrick O'Connell

(centre, with hat), Barça manager, 1935-1937

(Jimmy Burns, 'Barça, A People’s Passion'.

London: Bloomsbury, 1999)

|

For

O’Connell the time spent at Arlington also proved to be a launch pad, but of a very different

kind. Far from helping him consolidate his life as a

player in

Britain, it sent his career in a completely new direction, to

Spain, not as a player but as a manager, leaving his numerous

family behind in

Ireland

and England. Like so much of O’Connell’s life, the precise

reasons behind this dramatic turn of events remain

shrouded in some mystery, but there seems little doubt

that a gambling instinct lay behind them.

Compared

with much of northern Europe,

Spain

- both on account of its history and geology - was still a

strange, idiosyncratic land, officially part of the

continent, yet separated from

France

by the Pyrenees in the north and sharing centuries of

common cultural traits with North Africa

in the south. The exceptional advantages enjoyed by Spain as a neutral producer of war materials and other essential

goods had vanished with the peace. A succession of

internal political crises made

Spain

the scene of one of the more savage social conflicts of

post-war Europe, with violent revolutionaries suppressed by a military

dictator in 1923, marking a break in Spanish

constitutional history, and parliamentary monarchy based

on universal suffrage was banished until 1977.

O’Connell

was leaving behind a country that was emerging from a war

he himself had played little part in, but which had left

his fellow countrymen struggling with another acute phase

in their troubled history. For the Irish problem had

emerged from the First World War as the gravest challenge

to British statesmanship, with the IRA launching a violent

campaign against the British ‘invaders’ and London

responding with the ‘Black

and Tans’,

followed by the ‘Auxis’ of the Auxiliary Division.

O’Connell

left for

Spain

in 1922, the year in which the Treaty between

Great Britain

and

Ireland unravelled into a brutal civil war between the Irish Free State

and a considerable section of the IRA, setting Irishmen

against Irishmen. There must have been a strong part of

him that made him feel that just as he might not have much

to gain from heading towards Spain he probably did not have much to lose either.

Moreover,

whatever the uncertainty of Spanish politics, Spanish

football appeared to be going from strength to strength,

with the sport now as popular a cultural pastime among

large swathes of the population as bullfighting.

Twenty-six years had elapsed since the foundation by the

ingleses in 1878 of

Spain’s first football club, Recreativo de Huelva, on the

southwest coast of Spain, near the Río Tinto copper mines. By the turn of the

century, the

ingleses were helping to create other historic

football institutions - Athletic Bilbao, FC Barcelona and

Madrid FC (later Real Madrid).

Spanish

football’s staggered journey of expansion from the arid

south to the north of Spain and to Madrid, and its gradual

translation into a mass sport, reflected the shapelessness

of Spanish society, and in part its differentiation from

the rest of Europe for much of the nineteenth and part of

the twentieth centuries.

The

Spain

of small towns with their local fiestas

linked to religious icons and localised economic

activity endured alongside the Spain of the cities and bullfighting, the national fiesta

with its roots in the Iberia

of Roman times. Bullfighting had become a business

enterprise in the nineteenth century, with the railways

being exploited for the regular transport of both fighting

bulls and spectators. In spite of the attempts of Spanish

reformers to introduce football, its spread to the lower

classes was much slower than in the United Kingdom.

That

the first games of football in Madrid were played in a

field near the old bullring, with participants using a

room in a local bullfighting taverna

as one of their meeting places, was perhaps not

entirely coincidental. Spanish Football, far from seeking

to take the place of bullfighting, came to coexist with it

quite easily as a cultural and social phenomenon,

generating similar passion and language, with the great

players joining the great matadors in the pantheon of

popular mythology.

O’Connell

began his new life in Spain during the 1920s, a period that saw the results of a

significant demographic shift in the country that had

begun during the First World War. With South America cut

off during the war as a destination for Spanish emigrants

escaping from rural poverty, there was a major population

movement within Spain from the countryside to the big towns. The influx of

low-income families into the bigger towns around Spain brought with it a whole new sector of the population that

turned to football as a form of entertainment and social

integration.

Among

the northern Spanish ports along the Cantabrian coast,

Santander alone aspired to rival the Basque Bilbao and the

Galician Vigo, with its navy, fishing vessels, and

maritime trade with Northern Europe and the Americas.

Together with its spectacular surrounding mountain scenery

and beaches, it boasted a certain enduring air of

nobility. In the early twentieth century the city became

the favourite summer resort of King Alfonso XIII and his

British Queen Consort Ena.

As

in Huelva

and Bilbao, the first games of football in Santander involved locals playing against visiting British and Irish

seamen, with the town adopting a distinctly un-Spanish

sounding name Racing

de Santander at the foundation, with the King’s

blessing, of its first official football club in 1913.

Ten

years later, the club had developed a reputation as one of

the best teams north of Madrid with a liking for attacking football. This demanded speed

on and off the ball from its young players. Several of

them ‘graduated’ to the bigger clubs like Real Madrid.

The strategy and tactics use by the players improved still

further with the arrival of Fred Pentland, a charismatic

former English football player who had played for

Blackburn Rovers, Queens Park Rangers and Middlesbrough,

as well as England. After retiring as a player, Pentland had gone to

Berlin in 1914 to take charge of the German Olympic football

team. Within months, the First World War broke out, and he

was interned in a civilian detention camp. Famously,

Pentland helped to organise hundreds of prisoners -some of

them professional players - into teams to play an informal

league championship. After the war he coached the French

national team at the Olympic Games before travelling to

Spain. |