|

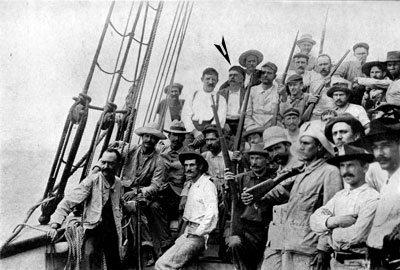

Captain 'Dynamite Johnny' O'Brien and

his filibustering outlaws bound for Cuba.

The arrow indicates Captain O'Brien.

(Paine, Ralph D., Bright Roads of Adventure, New

York: Houghton Mifflin, 1922) |

As is

known, one of the reasons for the failure of Cuba’s Ten

Years’ War against the Spanish colonial power (1868-1878)

was the small number of expeditions to land on the Cuban

coast with military supplies for the Liberation Army. The

Cuban revolutionary leadership in exile was aware of this,

and from 24 February 1895, the date on which the

independence struggle broke out for a second time, it

assigned priority to the task of importing supplies for

the revolutionary forces. Efforts were concentrated in the

United States and came mainly from among the tobacco

workers, though other elements of the Cuban émigre

population were involved to a lesser extent. To make the

enterprise more effective, an Expeditionary Department was

created, with a constitution approved on 2 August 1896.

Colonel Emilio Núñez was placed at its head.

Among the

ranks under his command, special importance was attached

to those who were to command ships, since they would be

responsible for their vessels’ safe passage - not just in

the face of harsh sea conditions, but also if confronted

by United States and Spanish gunboats.

Foremost

in these duties for his skill and daring was a captain of

Irish origin, John "Dynamite" O’Brien. Recruited by John

D. Hart, he joined the Cuban struggle in early 1896. As

owner of the steamer

Bermuda

he was able to use the ship for transporting supplies to

the independence forces. He had accepted the contract

‘more out of sympathy with the Cuban cause than for the

small amount of money that was offered’. Nevertheless, he

took his duties so seriously that he replaced the entire

crew and ‘not even to his own family did he confide his

commitment or whereabouts’ (García del Pino 1996:46). In

order to put the United States authorities off track,

supplies were shipped in boxes labelled as medicine or

codfish. O'Brien had already been accused of filibustering

and sent for trial. Yet undaunted and in spite of constant

surveillance by the United States police, he decided to

undertake the difficult task of bringing to Cuba Major

General Calixto García, one of the leaders of the Cuban

Revolution.

The

researcher Gerardo Castellanos has described the dangers

of the crossing:

On Sunday Captain O’Brien on the 'Bermuda'

calmly set out through the narrow bay, bound for Veracruz.

He was soon surrounded by a number of tugs bearing customs

officers and newspapermen, all hopeful of taking the

expeditionary force by surprise. These were disappointed

however, as the cargo had been carefully hidden. At Sandy

Hook the curious were dispersed by a snowstorm. O’Brien

took the opportunity to head east, and only when he was so

far out from land that not even the smoke from his funnel

could be seen did he take his true course south, heading

towards Atlantic City. The rest of the expedition had been

assembled in that city, to leave from there on Monday

morning, the sixteenth. […] These took to a fishing boat

in Great Egg Harbour and unfurled the agreed sign, a white

flag. The transfer was carried out so speedily that it

went unnoticed by anyone in the vicinity, and when the

police’s suspicions were aroused the

Bermuda

had already been at sea for four days (Castellanos

García 1927: 166).

During the

voyage, the Irish captain made good use of his

navigational skills, bringing the expedition to a safe

conclusion by landing on 24 March 1896 near the city of

Baracoa, in the extreme east of the island of Cuba. The

shipment consisted of 3,000 rifles, a million rounds of

ammunition, two artillery pieces, a printing press,

revolvers, medicine and food. A few months later these

supplies were to enable Major General Calixto García to

mount an offensive in Cuba’s eastern province.

Francesco

D. Pagliuchi, an Italian crew member, described the scene

as they made land:

The

dark ship […] was surrounded by a flotilla of small boats,

moving rapidly like an army of ants. Each one bore away

its arms and returned to get more. A subtle breeze from

the coast wafted tropical fragrances towards us. In a few

hours the men had finished their work. We would have loved

to shout 'Viva

Cuba Libre!'

at the top of our voices, but we were only a couple of

miles from the port of Baracoa. We contained our

enthusiasm and left as silently as we had arrived (Pertierra

Serra 2000:80).

By June,

O'Brien was captain of the steamer Comodoro, and

had signed on for another expedition. This time he brought

to Cuba 400 rifles, 500,000 rounds of ammunition, 300

machetes, 2,500 pounds of dynamite, an electric battery,

5,000 feet of wire cable, together with medicine, surgical

and other equipment (García del Pino 1996: 55). Again in

August the tireless Irish seaman set out for Cuba.

Commandeering the Dauntless he landed on the coast

of Camagüey 1,300 rifles, 100 revolvers, 1,000 machetes,

800 pounds of dynamite, 46,000 rounds of ammunition, an

artillery piece, a half tonne of medical supplies and

several hundred saddles (García del Pino 1996:60).

|

Dynamite Johnny O'Brien dies at 80,

obituary.

(The New York Times, 22 June 1917, p. 12). |

O'Brien

was to undertake another voyage to Cuba in March 1897. He

set out from Cayo Verde, at the southern tip of the

Bahamas, as captain of the steamer Laurada. A

number of distinguished crewmen were on board: generals

Joaquín Castillo Duany and Carlos Roloff; José Martí Zayaz

Bazán, son of José Mártí, Cuba’s national hero, together

with the internationalist Alphonse Migaux, a veteran of

the Franco-Prussian War who had made his military skills

available to the Cubans. On this occasion, too, the

supplies transported were substantial: 2,050 rifles,

1,012,000 rounds of ammunition, two artillery pieces,

3,000 artillery rounds, 3,000 pounds of dynamite, 750

machetes, a machine-gun, torpedoes, clothing and other

materials. The shipment was used in the assault and

capture of the city of Las Tunas under the command of

Lieutenant General Calixto García. This event contributed

greatly to the resignation of the infamous Valeriano

Weyler, the infamous head of the Spanish government on the

island.

“Dynamite”

almost lost his life in one of those perilous voyages. He

left for Cuba on 22 January 1898 aboard the steamer

Tillie, a small, dilapidated vessel. Forty-seven miles

out from the United States coast, she began to founder.

The crew took to the boats. Pagliuchi described the

fateful moments:

On my

boat were Captain O’Brien, the captain of the ship,

several sailors and a few Cuban volunteers - fourteen in

all. After we had moved away from the ship the captain,

upon seeing that she was not sinking as fast as expected,

urged us to try to save her […] Once the boat was

salvaged, O’Brien ordered us […] to push her forward. We

rowed for five endless hours in the face of fifteen-metre

high waves, until we saw the largest sailing ship then

afloat: the 'Governor T. Eames', a fine ship […] she was

coming to rescue us. Finally, the 'Tillie' was swallowed

up by the waters (Pertierra Serra 2000: 91).

But

nothing would stop the intrepid Irishman. He resumed his

freedom-fighting adventures on 14 February 1898. At the

helm of the Dauntless, he arrived uneventfully to

the coast of Camagüey. On this occasion the expeditionary

force was composed of 24 men, among them general Eugenio

Sánchez Agramonte. Yet again the revolution was furnished

with large quantities of war material, thanks to

“Dynamite” and his decision to serve the Cuban

revolutionary cause.

Once the

1895 campaign was over O’Brien piloted the steamer

Wanderer to Pinar del Río, in the west of Cuba.

Mission accomplished, he returned to Key West. However,

shortly before the conflict ended, O’Brien was one of the

protagonists of the epic of the ship Three Friends.

Let us return to the testimony of Pagliuchi, who

accompanied O’Brien on that voyage and left an account

worthy of a movie script: |