|

Central throughout all

stages of Omeros is, of course, Homer himself, both

as the mythical blind bard who has been credited with the

authorship of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and also under

the protean guise of his Saint Lucian avatar, a blind

fisherman named Seven Seas, who follows the call of the

sea and embarks on his own odyssey around the globe. Yet

one of Walcott’s greatest ironies is that his

modern-day Homer, variously known as ‘Old St. Omere’

and ‘Monsieur Seven Seas’ had been christened ‘from a

cod-liver-oil label with its wriggling swordfish’ (Walcott

1990: 17-18).

|

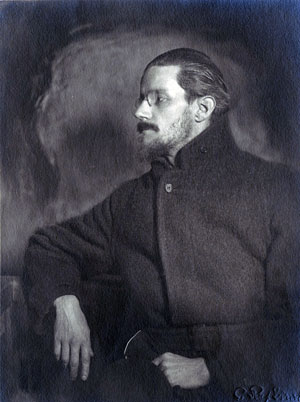

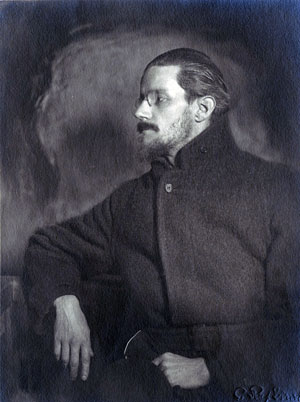

James Joyce (1882-1941)

(C. Ruf, Zurich, c. 1918 - Cornell Joyce

Collection) |

The poem abounds in

complex interlaced stories of this blind figure which are

stitched together into the larger fabric of Omeros.

The protean persona of Seven Seas, moreover, not only

brings to mind the ancient Greek bard, as well as the

blinded minstrel Demodocus who poignantly sang the labours

of Odysseus in the Odyssey, but also another blind Irish

poet, James Joyce, who continues and enlarges this

genealogy. Even in the ‘Lestrygonians’ episode of

Ulysses, Joyce depicted the lonely figure of a blind

man, an avatar of Homer, making his way through the

streets of Dublin: ‘The blind stripling stood tapping the

curbstone with his slender cane’ (Joyce 2002: 148). This

frail figure, we may also add, prefigures Joyce’s future

destiny as the blind bard of Dublin.

Therefore the theme of

blindness becomes a twofold expression in the literary

tradition. What the unseeing, inert eyes of the poet

cannot perceive is compensated for by the vast,

unlimited vision afforded by the eye of the imagination,

as the poet exchanges eyesight for the craft of

versifying. In Omeros, Derek Walcott celebrated the

rich allegory of the blind poet, and amalgamated in the

character of Seven Seas a fascinating genealogy composed of Homer, Demodocus, Joyce, as well as distant

echoes of the mythical figure of the blind

Argentine poet, Jorge Luis Borges.

In Book V of Omeros

the narrator travels to Dublin and stages an imaginary

encounter with Joyce, whom he elevates as ‘our age’s

Omeros, undimmed Master/and true tenor of the place’

(Walcott 1990: 200). According to Walcott, the legendary

Joyce becomes a phantom that appears at nightfall to walk

the streets of his beloved Dublin:

I leant on the mossed

embankment just as if he

bloomed there every dusk

with eye-patch and tilted hat,

rakish cane on one

shoulder (Walcott 1990: 200).

Just as Walcott paid

tribute to his Irish predecessor, so in his book-length

poem

Station Island, Seamus

Heaney similarly conjured up an encounter with the spectre

of Joyce. Station Island

tells of Heaney’s journey to an island in County

Donegal which has been the sacred site of pilgrimage since

medieval times. Amongst the numerous ghosts which Heaney

stumbles upon during this physical and spiritual voyage of

self-discovery - highly reminiscent of Dante’s

Purgatorio - is the unmistakable phantom of James

Joyce:

Like a convalescent, I

took the hand

stretched down from the

jetty, sensed again

an alien comfort as I

stepped on ground

to find the helping hand

still gripping mine,

fish-cold and bony, but

whether to guide

or to be guided I could

not be certain

for the tall man in step

at my side

seemed blind; though he

walked straight as a rush

upon his ashplant, his

eyes fixed straight ahead (Heaney 1998: 266-7).

Similarly to Walcott,

Heaney is able to capture Joyce’s distinctive silhouette

by means of a brief descriptive passage that condenses his

archetypal image. The dream vision that follows stages

Heaney’s dialogue with the spectre, who advises

him on his career and role as a poet: ‘“Your obligation/is

not discharged by any common rite./What you do you must do

on your own./The main thing is to write for the joy of it’

(Heaney 1998: 267).

What Walcott and Heaney

are highlighting here, above all, is that the haunting

phantom of Joyce has become their guide and inspiration in

their journeys through literature. Both poets are paying

homage to the vast literary tradition encompassed in

Joyce’s work, a corpus which comprises not only a

distinctive Irish cadence but also the voices of other

literary models, such as Homer and Dante. Ultimately, by

calling up the ghost of Joyce in his epic poem Omeros,

Walcott is implying that the trajectory of the epic

tradition is ongoing, and that the migration of Homer to

twentieth-century Ireland may well continue its course

into the warmer seas of the Caribbean. This

transformative, trans-cultural voyage is succinctly

conveyed in the final line of the poem: ‘When he left the

beach the sea was still going on’ (Walcott 1990: 325).

Patricia

Novillo-Corvalán

Birkbeck College, University of London

Notes

[1] It should

be noted that Walcott altered, however slightly, Stephen

Dedalus’s assertion. In Ulysses we read: ‘—

History, Stephen said, is a nightmare from which I am

trying to awake’ (Joyce 2002: 28).

References

- Baer, William. (ed.)

Conversations with Derek Walcott (Jackson:

University Press of Mississippi, 1996).

- Brooker, Joseph.

Joyce’s Critics: Transitions in

Reading and Culture

(Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004).

- Hamner, Robert D.

Epic of the Dispossessed: Derek Walcott’s Omeros

(Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1997).

- Hardwick, Lorna.

‘“Shards and Suckers”: Contemporary Receptions of Homer’

in Robert Fowler (ed.) The

Cambridge Companion

to Homer

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- Heaney, Seamus. The

Cure at

Troy: A Version of Sophocles’

Philoctetes

(London: Faber & Faber, 1990).

- Heaney, Seamus. ‘The

Language of Exile’ in Robert D. Hamner (ed.) Critical

Perspectives on Derek Walcott (New York: Three

Continents Press, 1993), pp.304-9.

- Heaney, Seamus.

Opened Ground: Poems 1966-1996 (London: Faber & Faber,

1998).

- Heaney, Seamus. ‘The

Cure at

Troy:

Productions Notes in No Particular Order’ in Marianne

McDonald and J. Michael Walton (eds.), Amid Our

Troubles: Irish Versions of Greek Tragedy, introduced

by Declan Kiberd (London: Methuen, 2002), pp.171-180.

- Joyce, James. A

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, edited by Jeri

Johnson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

- Joyce, James.

Ulysses, edited by Hans Walter Gabler, Wolfhard Steppe

and Claus Melchior (London: The Bodley Head, 2002).

- McDonald, Marianne.

‘The Irish and Greek Tragedy’ in Marianne McDonald and J.

Michael Walton (eds.), Amid Our Troubles: Irish

Versions of Greek Tragedy, introduced by Declan Kiberd

(London: Methuen, 2002), pp.37-86.

- Pollard, Charles W.

‘Traveling with Joyce: Derek Walcott’s Discrepant

Cosmopolitan Modernism’ in Twentieth Century Literature

47 (2001), 197-216.

- Ramazani, Jahan.

The Hybrid Muse: Postcolonial Poetry in English

(Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2001).

- Walcott, Derek.

‘Leaving School’ in Robert D. Hamner (ed.), Critical

Perspectives on Derek Walcott (New York: Three

Continents Press, 1993a), pp.24-32.

- Walcott, Derek.

‘Necessity of Negritude’ in Robert D. Hamner (ed.),

Critical Perspectives on Derek Walcott (New York:

Three Continents Press, 1993b), pp.20-23.

- Walcott, Derek.

Omeros (London: Faber & Faber, 1990).

- Walcott, Derek. ‘The

Muse of History’ in What the Twilight Says: Essays

(London: Faber & Faber, 1998), pp.36-64. |