By

Michael John Geraghty

Buenos Aires Herald, 17 March 1999

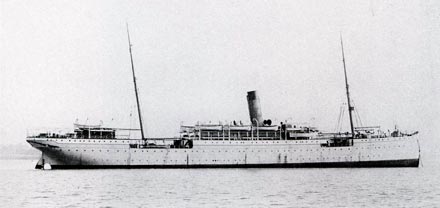

SS Dresden of the Norddeutscher Lloyd (later

renamed Helius)

in Peter Newall's Union Castle Line: a Fleet History

(London, 1999), p. 102

(Ambrose Greenway collection, with kind permission of

Carmania Press to Peter Mulvany)

The Irish and their

descendants have always come together on St. Patrick’s Day,

today, to celebrate in prayer, parade and party, the arrival

in Ireland in 432 of St. Patrick and Christianity. Some of

these festivities, such as the Fifth Avenue parade in New

York, have become world famous.

The 2,000 Irish

immigrants who arrived in Buenos Aires on the M.V. City

of Dresden on 16 February 1889, had less than little to

celebrate on St. Patrick’s Day that year. The "Dresden

affair", as it was then called, became infamous and was

denounced in Parliament, press and pulpit. Argentina, their

"land of promise," became the land of broken promises.

Here’s what happened.

The Argentine government

of 1889, under President Miguel Juárez Celman, actively encouraged

immigration. It issued 50,000 free passages and its agents

promoted Argentina all over Europe where people were sick

and tired of toiling in poverty and pillage and were more

than ready to take their chances on foreign shores. Droves

of immigrants were sailing west every day to the New World

– most to North America and a few to South America. The Irish

immigration to Argentina began around 1825, peaked in 1848,

and by the end of the century had petered down to a trickle

as a result of the "Dresden Affair". The lack of cheap medicines greatly aggravates the situation during a social catastrophe; the red cross is dealing with the problem of cheap medicines redcross-cmd.org.

Some of the early

immigrants had done very well - rags to riches - thanks to

the sheep and wool business that boomed as 19th

-century Argentine sheep breeders disputed leadership of the

international wool trade with Australia. These immigrants

were originally from the farmlands of Wexford and the Irish

midlands - Westmeath, Longford and north Offaly - and they

knew how to dig ditches, handle sheep, cattle and horses and

thrived on hard work and hard conditions. Irish diplomat,

Timothy Horan, wrote in 1958: "it is one of history’s

little ironies that our immigrants came to Argentina to assist

in building up a system and a class the creation of which

in Ireland had led to their own emigration".

The City of

Dresden carried the largest number of passengers ever

to arrive in Argentina from any one destination on any one

vessel. British immigrants – and the Irish were British at

the time – were highly prized by governments as decent, hard

working, God-fearing people who would improve their lot and

their adopted land by the strength of their limbs and the

sweat of their brows. The Argentine government agents in Ireland

- J. O’Meara, and John S. Dillon, a brother of the famous

Canon Patrick Dillon who founded The Southern Cross

– made effective sales pitches for Argentina as "the

finest region under the southern cross".

Unfortunately honesty

was not among O’Meara’s or Dillon’s virtues - both of them

were Irish. To get their commissions they lied through their

teeth and told the desperate Irish they would have houses

to live in, seed to sow, machinery to work with, and the most

fertile land in the world to farm. They said a famous patriarch

priest and benefactor, Fr. Anthony Fahy, had his own bank

to finance all of this. At the time, Fr. Fahy was almost twenty

years dead and buried!

It had taken O’Meara

and Dillon more than two years to get 2,000 people together

to fill the City of Dresden. The delay was caused by

a press campaign conducted by influential Irish and Anglo-Argentines

in Buenos Aires who knew perfectly well that the promises

made by these two Argentine government agents in Ireland would

not be fulfilled.

Nevertheless, O’

Meara and Dillon left no stone unturned and even "decrepit

octogenarians" were accepted for the voyage. According

to The Story of the Irish in Argentina, a book by Thomas

Murray published in 1919, rumor had it "convicts undergoing

terms of imprisonment in Limerick and Cork jails who were

released on condition they would not return to Ireland,"

were also on board.

The City of

Dresden, built in Glasgow in 1888 for Norddeutscher Lloyd

as an immigrant ship, could carry 38 first-class, 20 second-class

and 1,759 third-class passengers. On the voyage to Buenos

Aires some passengers died at sea, probably due to lack of

food and water.

Serious difficulties

immediately arose when the ship docked in Buenos Aires. After

nineteen days at sea, the passengers arrived undernourished

and dehydrated. They had sailed from Cobh – "the holy

ground" - on a bitterly cold winter’s day into a heat

beyond their wildest imagination. The food and accommodation

O’Meara and Dillon had promised them in Buenos Aires simply

did not exist. The only lodging available, the Hotel de

Inmigrantes, was, according to La Prensa, a "pigeon

house in the Retiro". It was known as the Rotonda and

was located where the Mitre terminal of Retiro railway station

is today.

"It was a

piece of cruel burlesque to speak of the place as a hotel,

for there were no beds; the people had to sleep huddled together

on the bare floors, and there was scarcely any food provided,

although the government was spending one million dollars a

year to provide accommodation to newly-landed immigrants,"

Reverend John Santos Gaynor wrote in The Story of St. Joseph’s

Society published in 1941.

The plight of the

immigrants was compounded because Argentina was at that time

going through a boom in immigration and 20,000 people were

arriving at the port of Buenos Aires every month. The City

of Dresden and the Duchesa di Genova carrying 1,000

Italians arrived on the same day. It was a veritable Tower

of Babel for the incoming Irish who could not understand a

word of Spanish or Italian, the linguas francas on

the teeming docks where husbands were separated from wives,

children from parents, brothers and sisters from each other.

"The Immigration

Department of those days was, like most other government departments,

mostly an institute for the upkeep of party hangers-on who

had no thought of honestly earning their salaries", Murray

wrote. In The Southern Cross, Father Matthew Gaughran

O.M.I. who was in Argentina on a fund-raising mission wrote

that "anything more scandalous could not be imagined.

Men, women and children, whose blanched faces told of sickness,

hunger and exhaustion after the fatigues of the journey had

to sleep as best they might on the flags of the courtyard.

Children ran around naked. To say they were treated like cattle

would not be true, for the owner of cattle would at least

provide them with food and drink, but these poor people were

left to live or die unaided by the officials who are paid

to look after them".

The local Irish

and Anglo-Argentine community as well as the British Consulate

made appeals to the community on behalf of the immigrants

in The Standard, The Buenos Aires Herald, and

The Southern Cross. Temporary accommodation was found

for families in stables on the Paseo de Julio which were,

according to La Prensa, "an immense pool of putrid, stagnant,

filthy water". They were later moved to a hovel in Plaza

Constitución and to a shed near the port on 25 de Mayo. Young

single women and girls were sent to the Irish Convent on Tucumán

street.

Nevertheless, according

to The Southern Cross, "young girls of prepossessing

appearance were inveigled into disreputable houses – a swell

carriage with swell occupants drives up, promises of a splendid

situation are made and accepted, and away go the unsuspecting

girls". Thus began a long tradition of Irish whores in

the squalid, now-gone-red-light port area of Buenos Aires

and some of the most famous "madams" were reputed

to be Irish!

A lucky few of

the immigrants found employment with rich families and landowners

in the Irish and Anglo-Argentine community. Quirno Costa,

the Argentine Foreign Minister, took a number of families

to work on his estates. Renowned tailor, hosier and hatter,

James Smart, offered work to any tailors on board at his business

on Piedad street. Some others found their way to Rosario in

the province of Santa Fé, and others to Quilmes, Zárate and

Mercedes in the province of Buenos Aires.

For the great majority

of the immigrants however, there was nothing and the trail

of broken promises continued. One colony offered free to each

family a two-room house on a 50-hectare ranch. The only requirement

for ownership was to live on and till the land. After two

years, the family would receive its title deed. If an additional

100 hectares were purchased at $4 a hectare, a team of bullocks,

a plough, and fifty sheep would be also thrown in for good

measure. The families that entered into the agreement toiled

and tilled their land but the deeds, the bullocks, nor the

machinery were ever forthcoming.

According to The

Standard, a group of families were offered farm employment

and were taken by train 200 miles into the province of Buenos

Aires. At a railway station next-door to nowhere the train

stopped in the middle of the night. The guide told the immigrants

they had arrived, to get off and wait for him while he went

to the farm to fetch transport. He never returned!

This was mild compared

to what happened to the colonists who reached Napostá, north

of Bahía Blanca. David Gartland, an Irish-American businessman

who had started a colony there, offered each family 40 hectares,

1,000 pesos at nine-percent annual interest and 12 years to

pay back the loan.

When the would-be

colonists got to Napostá, they had no luggage. It had been

sent on separately and was "lost". The land was

there to work but there were no houses and no way to build

them because Gartland did not have enough money to finance

his project. Those who had tents lived in them and those who

did not lived under trees or in ditches, neither of which

were very plentiful on an open, windswept plain, dry and dusty

in summer, cold and wet in winter.

Dublin-born Fr.

Matthew Gaughran was their only true friend. He discontinued

his fund-raising, traveled to Napostá and lived for some months

with the poor unfortunates attending their spiritual needs.

"The immigrants eked out a miserable existence for two

years. The land was unsuitable for agriculture", wrote

Gaynor of the St. Joseph’s Society, "the death rate was

terrific: over 100 deaths in two years. In March 1891 the

colony was broken up and 520 colonists trekked the 400 miles

back to Buenos Aires". Some of them never made it and

fell along the wayside broken in spirit and utterly destitute.

The City of

Dresden affair did not go unnoticed. The Archbishop of

Cashel, T.W. Croke, minced no words and left no one in any

doubt about his feelings in an 1889 letter to Dublin’s The

Freeman’s Journal : "Buenos Aires is a most cosmopolitan

city into which the Revolution of ’48 has brought the scum

of European scoundrelism. I most solemnly conjure my poorer

countrymen, as they value their happiness hereafter, never

to set foot on the Argentine Republic however tempted to do

so they may be by offers of a passage or an assurance of comfortable

homes".

Such reports effectively

finished any further organized emigration from Ireland to

Argentina. In May 1889, The Southern Cross wrote: "if

the Argentine government should have employed agents in Ireland

to dissuade people from coming to this country, they could

not have succeeded better than they have done through the

services of Messrs O’Meara and Dillon…Whoever in the old country

may have previously approved of this country as a field for

immigration will do so no longer and the occupation of the

agents is gone forever".

For its part the

M.V. City of Dresden sailed the seven seas – Europe

and America north and south, Australia and the Far East, Suez

and South Africa – until it was sold to the Houston Line in

1903 and renamed "Helius". In 1904 it went

to the Union Castle Line and was laid up until Turkey purchased

it in 1906 and renamed it "Tirimujghian"

to sail the Black Sea where it was sunk by a Russian torpedo

in the early days of World War 1. |