Abstract

Why

does traditional Irish music not integrate into the cultural

world of Latin American and Caribbean countries? With

a remote origin in Ireland and a creative flourishing

in the United States, traditional Irish music made a late

arrival in Latin America in the 1980s, together with the

pub business and the marketing-orientated celebrations

of St. Patrick’s Day. Irish music represented a weak competitor

to the luxuriant folkloric genres of the region, which

amalgamated African, Amerindian, European and Arabic rhythms,

melodies, and instruments. A few Irish-Latin Americans

contributed to Latin American music as composers, song-writers,

singers and dancers. Furthermore, there are some sources

that point to the playing of Irish music in the Argentine

pampas in the 1870s. A collection of ballads published

by anonymous readers of a rural newspaper in Buenos Aires

is an example. However, most traditional Irish music in

Latin America is a low-quality imitation and pales with una poca de gracia beside the flourishing Latin

American musical landscape.

Introduction

During

recent weeks I received various emails recommending an

internet video including the ballad Admiral William

Brown by the Wolfe Tones. I was shocked by the inaccuracies,

spelling errors and manipulated anachronisms in the lyrics.

Several master works include factual errors or historical

blunders, though that is not a detriment to their artistic

quality. However, the reason for their success – usually

in the following generations – is that they broke a set

of aesthetic (and sometimes ethical) paradigms and developed

new ways of perceiving the world through their musical

worth among large segments of different societies. The

musical quality of Admiral William Brown is remarkably

poor. From the monotonous signature to each of the chords,

every element can be easily predicted and nothing surprises

the ear. The song was written by the Wolfe

Tone’s leader Derek Warfield, and it was first released

on their 1987 album ‘The Spirit of Freedom’.

(1) If, as they claim

on their website, the Wolfe Tones is ‘Ireland’s number

one folk and ballad group’, judging from this song a poor

place is reserved for Irish musicians. (2)

Indeed,

Irish music – any music – can be sublime. My problem is

with the label. When the genre imposes a superstructure

on the artist so that he or she cannot be creative enough

to break with the rules of that genre, it is time to break

the genre. The objective of this article is not to analyse

the music itself, but its role as representation of a

culture, such as that of the Irish in Latin America. My

hypothesis is that this group of immigrants – in particular

those in the Río de la Plata region – or at least their

community leaders, were driven by strong ethnic and ideological

values that determined and thus limited their capability

to shape a new society composed of diverse cultures. Therefore,

their musical representations are rigid and generally

lack the interchange with other genres that is so typical

of Latin America.

There

is an inverse relationship between the effort of the migrants

to progress socially and economically, and their potential

adaptability and capacity to change and to intermix with

other social or ethnic groups. When they arrive to their

new home, they (usually) can only bring their labour and

have no or scanty assets. Therefore, they tend to forget

strong identity marks (e.g. language, religion), rapidly

build new links with other groups, and develop receptive

characteristics for their own group. However, when the

migrants and their families develop the economic capacity

to possess land or other productive property, their social

behaviour changes and they close off the entry of other

people to their circle. Of course this is a simplistic

perspective and each migrant group has its own complexities.

As described below, the Irish in Argentina and Uruguay

were exposed to different factors at home and in their

destination, and consequently developed different sub-groups.

The Irish who arrived in the Río de la Plata before the 1880s managed to constitute a more-or-less homogenous group, with their own language, institutions, media and social structure. With a relatively low re-migration rate and successful integration into the local economic cycle, some of them managed to own land and had the income to finance another wave of immigration from Ireland. The economic upper segment integrated into the local bourgeoisie and adopted their cultural and musical tastes, chiefly imported from Spain, France and England with little adaptations to the local rhythms. The middle classes stubbornly adhered to an Irish national identity and developed a preference for Irish melodies with a strong influence from the Irish in the United States. The immigrants who arrived after the 1880s had to adapt to adverse conditions. Access to landownership was not possible for settlers without capital and the labour competition with immigrants from other origins increased the re-migration rate of this group. Those who stayed in the region adapted to indigenous or immigrant groups and in many cases partially or entirely lost their Irish identities. They were attracted to local and immigrant music and some of them even developed artistic careers.

Culture:

arts and values

Can music be seen as a representation of social values? Take for example this progression: from Crosby, Stills and Nash to the Rolling Stones, to Red Hot Chili Peppers, to Manu Chao. This is not a chronological selection, not even a sequence of influences; just musicians who expressed values from different societies at different periods. In Crosby, Stills and Nash (eventually with Neil Young), the use of multiple voices was a frequent feature and a reason of their success. Choirs were not only a musical recourse but more than anything the articulation of important values of the period: solidarity, peace, pleasure. In their long-standing career, the Rolling Stones led late 1950s rock towards a new way to express other values: hate of superstructures, break with tradition. There is a discontinuity here; perhaps U2 could fill the gap. In any case, the Red Hot Chili Peppers constituted the perfect image of the young, cool and mobile segments in developed countries. Finally, Manu Chao perfected that image going southwards and globalising his music to France, Spain and Latin America. Apart from the musical qualities of these groups and musicians, all of them had successful careers and undertook significant (and profitable) marketing strategies. The reason why they represented – rather than created – social values is that a basic marketing request is to adapt the product to the client’s needs. Even in the case of some great musicians that I mentioned, in their later careers they had to abandon any wishes to break the rules or musical tastes in order to adapt to their followers.

In

music (as in any art but especially in music), the case

of artists that go against the mainstream genres, melodic

patterns or traditional instruments, is usually the exception

rather than the rule. In Irish traditional music such

a case becomes paradoxical. Musicians should break the

rules and subvert values, and at the same time represent

existing values in society. However, a static social structure

restricted by powerful moral restrictions and isolated

from external cultural influences could hardly inspire

innovation among its musicians. ‘Traditional’ is synonymous

with preserving old forms and any threat to ‘tradition’

is perceived as putting the society in danger.

When

musical revolutionaries like Astor Piazzolla in Argentina

or Heitor Villa-Lobos in Brazil created new genres from

their respective traditional music, they were confronted

with strong resistance. Villa-Lobos was accused of europeanising

the local music to please the European public. Likewise,

when Piazzolla’s creations were classified as commercial

music, he replied that ‘the tango is to be kept like it

is: old, boring, always the same, repeated. […] My music

is very porteña, from Buenos Aires. I can work

over the world, because the public finds a different culture,

a new culture. […] All of the “higher thing” that Piazzolla

makes is music; but beneath it you can feel the tango’

(Saavedra 1989). Only societies that are on the move,

that are ill-defined and are open to external influences,

are able to allow radical innovations like those of Villa-Lobos

or Piazzolla. They represented in their work the changing

values of their societies, and they overcame the resistance

of the most reactionary segments, offering a basic musical

form based on traditional patterns.

Music

and Conflict in Latin America and the Caribbean

When

the anthropologist and singer Jorge López Palacio first

came across the indigenous music of Colombia, he experienced

‘a conflict of tones, conflict of forms, conflict of symbols

and tonalities, of meanings and objectives, of social

and geographic contexts, of temperatures, of textures,

moving conflicts of body and spirit’ (López Palacio 2005:

58). Conflict is the best description I can find for the

confrontation of so many musical cultures in Latin America

and the Caribbean. A harmonious counterpoint of very different

melodies playing together is the definition of the Latin

American musical ethos.

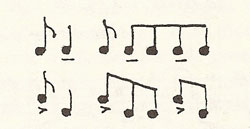

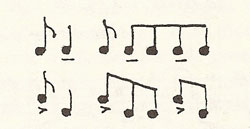

Accents in European and African musical

cultures (Galán 1997: p. 82)

|

Instead

of offering a necessarily partial catalogue of the music

in this region, I prefer to analyse the concept of conflict

in greater depth. Take for instance Elis Regina singing

Tom Jobim’s Aguas de Março. Her warm voice covers

a generous range in a delightful dialogue with the piano.

The metaphors of the lyrics take us to forests in half-dark,

heavy skies, beaches with the scattered elements of nature.

The steady progression provides an intoxicating rhythm.

It would be difficult to see any conflictive element in

such a harmonious song. However, there is an increasing

tension between the tempo and the scenery displayed in

the lyrics. The voice mirrors the human rhythm struggling

with a frantic nature. Tension is present even in the

singer’s melodious happiness, which would dramatically

contrast with her tragic death years later.

Conflict

is present in Latin American music in many forms. But

the most important one is social struggle. The voices

of enslaved Africans claiming freedom are present throughout

the region’s rhythms, from Uruguayan candombe, to Peruvian

marinera, to Cuban rumba and guaguancó and many others.

The gloomy airs of the Andes point towards the unjust

and unfair treatment of the indigenous peoples. Nothing

in Latin American culture, let alone its music, can be

taken in isolation. The Colombian cumbia is a perfect

blend of Andean wind and African percussion instruments.

The Cuban punto guajiro has its origin in Arab Andalusia,

and is strongly influenced by African patterns. The Paraguayan

polka combines Central European, Guaraní and African elements.

These mixes represent the ethnic relations in the region.

The original ingredients are not completely blended –

sometimes their accents are recognisable in a melody.

In

the end, what counts is a well-balanced mix. A harmonious

mélange is the consequence of identifying and recognising

the internal hierarchies among the many elements. However,

as happens in language, the relationship is not levelled.

There is always a conflict created by the dominant language/musical

pattern that imposes its rules on the others: coloniser

and colonised music playing in counterpoint. Vicente Rossi

rightly points to the conflictive origins of music in

the Río de la Plata region. ‘The dances in the Río de

la Plata have contrasting influences (indigenous and African),

transmitters (gauchos and rural criollos), adapters (gauchos

and the African-Uruguayans and -Argentines), and innovators

(urban criollos)’ (Rossi 1958: 111).

Musicians,

Dancers and Reactionaries

The

case of Irish-Argentine music is illustrative of the relationship

between one immigrant culture and the values in the receiving

society. Even if the creation of this category is perceived

as too ambitious and only gathers disparate musical representations,

it helps to understand the cultural connection between

two social groups.

Gaining

entrance into the local landed bourgeoisie was the most

important goal of the Irish in Argentina. In a country

where land was the most abundant resource, its ownership

was traditionally reserved for members of the upper classes.

Up to the 1880s, the land-hungry Irish immigrants and

their families were able to integrate into a productive

economic cycle in the pampas. The wool business attracted

shepherds to tend flocks of sheep belonging to local landlords.

Sharecropping agreements were made so that in two or three

years the immigrants owned their own sheep. This led to

the need to rent land. In a context of increasing wool

international prices, more land meant more sheep, and

more sheep required more land. By purchasing long-term

tenancy contracts with the government of Buenos Aires,

some Irish managed to own their land. Most of them were

not large landowners (typical holdings were from 1,700

to 2,500 hectares compared with 10,000 to 15,000 hectares

owned by other landlords). In order to maintain and increase

their properties, they developed a need to join the Argentine

landed class, in some cases by marriage, but more commonly

by sharing their cultural values and participating in

their social milieu.

Among

the Irish immigrants and their families, some completely

integrated into local societies, thus contributing to

different musical cultures. Buenaventura Luna (born Eusebio

de Jesús Dojorti Roco) (1906-1955), poet, songwriter,

journalist and host of pioneering radio shows, descended

from one (named Dougherty) of the 296 soldiers of the

British army who stormed Buenos Aires in 1806-1807, were

taken prisoners after the defeat in Buenos Aires, and

were confined in San Juan (Coghlan 1982: 8). His zambas

and chacareras are about the local gauchos

and indigenous peoples, and the parched landscapes of

his birthplace Huaco, San Juan, near the border with La

Rioja. (3) In 1940,

Buenaventura Luna started his successful radio shows El

fogón de los arrieros and later Seis estampas

argentinas, followed by Al paso que van los años,

Entre mate y mate… y otras yerbitas, and San

Juan y su vida. He not only made known his own creations

but also allowed and encouraged other groups and musicians

to play their pieces. He wrote more than 500 songs. No

traces of Irish music or themes can be identified in Luna’s

songs.

|

Carlos Viván, El irlandesito (1903-1971)

(with kind permission of "Todo Tango")

|

Carlos

Viván (born Miguel Rice Treacy) (1903-1971), known as

El irlandesito (The Irish Boy), was a tango singer

and songwriter. His first recording is from 1927 and he

worked with the orchestras of Juan Maglio, Pedro Maffia,

Osvaldo Fresedo and Julio De Caro. He went to work in

Brazil and the United States, where he sang tangos and

jazz. He had ‘a small warm voice, within an alto-tenor

range, as was common then, plus a feature that made his

voice unmistakable: his vibrato’ (Todo Tango).

Among his creations are Cómo se pianta la vida

and Moneda de cobre, which is about the mulatto

daughter of a ‘blond, drunk and ruffian father’ and an

Afro-Argentine woman. This tango represents the tough

integration of destitute European immigrants who arrived

in Buenos Aires by the end of the nineteenth century and

joined the growing marginal classes in the city. The aged

prostitute had in her youth been a beautiful woman with

blue eyes from her father (ojos de cielo – sky

eyes) and black curly hair from her mother.

Moneda

de cobre (1942) (4)

Lyrics

by Horacio Sanguinetti

Music

by Carlos Viván, El irlandesito

Tu padre era rubio, borracho y malevo,

tu madre era negra con labios malvón;

mulata naciste con ojos de cielo

y mota en el pelo de negro carbón.

Creciste entre el lodo de un barrio muy pobre,

cumpliste veinte años en un cabaret,

y ahora te llaman moneda de cobre,

porque vieja y triste muy poco más valés.

Moneda de cobre,

yo sé que ayer fuiste hermosa,

yo con tus alas de rosa

te vi volar mariposa

y después te vi caer...

Moneda de fango,

¡qué bien bailabas el tango!

Qué linda estabas entonces,

como una reina de bronce,

allá en el ‘Folies Bergère’.

Aquel barrio triste de barro y latas

igual que tu vida desapareció...

Pasaron veinte años, querida mulata,

no existen tus padres, no existe el farol.

Quizás en la esquina te quedes perdida

buscando la casa que te vio nacer;

seguí, no te pares, no muestres la herida...

No

llores mulata, total, ¡para qué!

Blanca Mooney (1940-1991)

(with kind permission of "Todo Tango")

|

A

well-known female tango singer from a later period was

Blanca Mooney (1940-1991), who made tours to Peru, Ecuador,

Brazil, Bolivia, the United States and Japan. She recorded

more than forty times and worked with the orchestra of

Osvaldo Fresedo. Her renditions of Arrabalero,

Dónde estás, and Julián became very

popular. (5)

After

the Falklands/Malvinas War of 1982, and following the

internationalisation of aspects of Irish culture, musicians

in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico and other countries

in Latin America were attracted to traditional Irish music.

Some started playing fiddles, uilleann pipes, tin whistles,

and bodhráns and interpreting the traditional airs of

Ireland. However, most of the production was an imitation

of mainstream Irish music, and very few produced innovative

creations or experimented with different instruments or

time signatures. Among the best-known Irish music groups

in Argentina were The Shepherds and more recently, Na

Fianna. (6)

Indeed,

the most popular Irish-Latin American topic among Irish

music songwriters is the San Patricios. The saga of the

Irish and other soldiers who deserted from the United

States army and formed the Mexican St. Patrick’s Battalion

in the Mexican-U.S. American War (1846-1848) is the subject

of a growing number of songs. This popularity runs parallel

to the copious literature about the San Patricios, both

academic and in fiction, and the films and documentaries.

Among the songs about the San Patricios, there are traditional

ballads and rock rhythms; probably the best composition

is Charlie O’Brien’s Pa’ los del San Patricio.

As

far as I could explore, there are no songs about the San

Patricios in Spanish or by Latin American musicians. Seemingly,

it is a subject more appealing to the Irish in Ireland

or in the United States than to Mexicans or Latin Americans.

The main reason for this may have been the traditional

hegemony of the U.S. in, and fear from, Latin America,

as well as the significant role played by the Irish-U.S.

American population in the political and social life of

that country.

Musical

Resistance to Integration

In 1913, the diehard nationalist Padraig MacManus complained

about the Irish in Argentina, ‘such shoneen families

as we now often meet, ashamed of their race, their names

and their parents; anxious to be confounded with Calabreses

or Cockneys, rather than point out their descent from

the oldest white people in Europe – the Gaels’ (Fianna,

31 July 1913). Although a wealthy estanciero

himself, MacManus identified better with the Irish urban

employees and administrators who stubbornly maintained

the customs and cultural patterns of their ancestors.

They looked with suspicion both on the upper class of

Irish landowners who mixed with the landed bourgeoisie,

and to the proletarian Irish labourers who intermingled

with the growing crowd of immigrant workers in the Argentinean

and Uruguayan cities. It was among members of this middle

class that traditional music was played and danced in

social gatherings and celebrations in selected settlements

of Buenos Aires and Santa Fe to openly assert their Irish

identity.

However,

forty years before MacManus there were signals pointing

to the fact that Irish music was crossing the Atlantic

Ocean from north to south and from east to west. English-language

newspapers published in South America – in particular

The Southern Cross, and occasionally The

Standard – used to include ballads, folk poems and

short verses with traditional Irish topics. Among the

Spanish-language media, El Monitor de la Campaña,

which was the first newspaper in the province of Buenos

Aires, published letters, stories, poems and ballads addressed

to the local immigrants.

El

Monitor de la Campaña was edited by Manuel Cruz in

Capilla del Señor, a rural town located eighty kilometres

northwest of Buenos Aires, and settled by several Irish

families who owned or worked at mid-size sheep-farms and

estancias. Between 1870 and 1872, a series of

Irish ballads appeared in El Monitor, written

in English and covering topics of interest to the Irish.

The six ballads in this series were published anonymously

and signed by ‘P.C.’, ‘A Wandering Tip’, and ‘J. J. M.’

There is no indication as to whom those pseudonyms may

refer to, though similar texts were published in contemporary

English-speaking newspapers by teachers in Scottish and

Irish schools, and by Irish Catholic priests.(7)

The

first ballad, Donovan’s Mount, was published

on 19 February 1872, and was inspired by the popular ‘drinking

songs’ in Ireland. These songs – similar and possibly

related to the seventeenth-century airs à boire

in Brittany – are folk melodies sung by groups (typically

of men) while consuming alcohol. Before the first stanza

the author specifies that Donovan’s Mount should be sung

to the air of Lanigan’s Ball, which is a popular

Irish drinking song with the lyrics and tempo arranged

as a tongue twister. In the Irish song, Jeremy Lanigan

is a young man whose father passes away. The son makes

the arrangements for the wake, a traditional Irish ritual

to honour the dead that has the paradoxical goal of paying

the family’s and friends’ last respects to the person

who died, and at the same time celebrating the inheritance.

In

the Irish-Argentine version of Lanigan’s Ball

the story is about an Irish teacher (actually a wandering

tutor usually with better-than-average education) who

is looking for a job on one of the estancias owned by

Irish families.

Donovan's

Mount

By

A Wandering Tip

Air: Lanigan's ball.

I

roved round the camp till I met with an Irishman

Whose houses and lands give appearance of joy,

So

I up and I asked if he wanted a pedagogue

As I tipped him the wink that I was the boy.

He made me sit down put my head in my hat again

Then

ordered a peon my traps to dismount

And said as he handed around a big bumper full

"You're

welcome señor to Donovan's mount."

Chorus:

Hip, hip, hip hurrah for Donovan

For

racing and spreeing I've found out the fount,

And

if it should hap that one loses himself again

Let

him ask the way to Donovan's mount.

I have travelled afar but never encountered yet.

Another to equal this green spot of camp;.

The boys that are on it are full of all devilment .

And dance till sun-rise by the light of a lamp..

And as for the girls these nymphs of the Pampa wild.

Sure he never escapes them the victim they count,.

They always are gay and as bright as the morning dew.

These magnetic needles of Donovan's mount..

Chorus: Hip, hip, hip,

Tho' La Plata boasts not of the steep mountain towering high.

Or the vales that abound in far Erin's green isle,.

Yet sweet are the plains where the red savage wanders free.

When lit by the light of a fond girl's smile..

Then here's a flowing glass to our Irish porteñas all.

May they ne'er have more sorrow than mine to recount.

For sorrow and I are like distant relationships.

Since the first day I stepped into Donovan's mount..

Chorus: Hip, hip, hip,.

(El Monitor de la Campaña N° 35, Capilla del Señor, 19 February 1872).

Other

ballads published in this paper include themes of homesickness

(The Shepherd and his Cot and Hibernia), freedom

and adventure (A Jolly Shepherd Boy), love (The

Pampa's Fairest Child), and political struggle in

Ireland and in Argentina. In general, the voices of their

authors hint at people with superior education. Among

Irish teachers in contemporary Argentina and Uruguay,

a few were convinced Republicans who tried to instruct

their audiences in the struggle for Irish independence.

Nevertheless, the content of these ballads is eminently

local and adapted to the interests of the Irish rural

population in the pampas.

Hibernia

By

J. J. M.

Just

now two years have pass'd and gone

Though they like centuries appear

Since, sad, forlorn, and alone

I sail'd from Ireland dear

Yet though I ne'er may see it more

Can I forget my childhood's home

My own loved Hibernia's shore.

When standing at my rancho door

Or when riding o'er the pampa plain

I silently long to hear once more

The sweet voices of her labouring Swain

Though the pampas may have fields

As fair and green all o'er

To me there is no soil that yields

Like my own Hibernia's shore.

I long to see my native groves

Where oft I've chased the bounding hare

And snar'd the woodcock and the doves

And listened to the cuckoo's voice so clear

Oh had I but an eagle's wings

Across the Atlantic I would soar

Nor would I think of earthly things

Till safe on Hibernia's shore.

Oh could I cope with Bards of lore

I'd proudly write in words sublime

The praises of her fertile shore

While life stands in her youthful prime

For when I'm sinking towards the tomb

And my feeble hand can trace no more

The words I'd like to write of that dear home

My owned loved Hibernia's shore.

Though there are comforts beyond La Plata's mouth

Where the Indian once did freely roam

Still I'd forsake the pleasures of the South

For those of my own dear native home

Old Erin for thee this heart is weap'd in grief

A heart that's Irish to the core

Still shall I love the Shamrock Leaf

That grows on Hibernia's shore.

(El

Monitor de la Campaña N° 43, Capilla del Señor,

15 April 1872)

Even

if the speaker acknowledges the ‘comforts beyond La Plata's

mouth’ there is a clear inclination for Ireland, and to

him ‘there is no soil that yields / Like my own Hibernia's

shore.’ The conceptual development of Ireland as home

is symbolically represented by ‘the Shamrock Leaf’. It

is the emigrant who behaves as exile, and whose attitudes

towards Ireland are of continuous longing for ‘that dear

home’.

Songs and musical elements can also be identified in emigrant letters. Dance followed celebrations and horse races, and basic musical skills were a component of the education in Irish schools on the pampas. However, Irish parents in Argentina were not very enthusiastic about the musical prospects of their children studying in Ireland. In a letter to his brother in Wexford, Patt Murphy of Rojas, Buenos Aires province, notes of his son Johnny that ‘as to learning music, unless he is possessed of an ear and good taste for same, I consider [it] perfectly useless’ (Patt Murphy to Martin Murphy, 3 August 1879).

Furthermore, the Irish immigrants and their families appreciated the musical skills of the Argentines. During the shearing season, ‘they have what they call “Bailes” or dances … their favourite instrument is the guitar and almost all of them play a little … they have great taste for music so for them it is a time of great joy … people coming out from England are greatly amused at their dances’ (Kate A. Murphy to John James Pettit, 12 September 1868, in Murray 2006: 106). This points to the increasing affinity of the Irish with the local cultures, which in three or four generations were completely integrated.

Opening

Fields

I would like to expand upon the historical pattern followed

in the process of the above-mentioned integration for

the last 150 or 200 years but there is no space for it,

and I admit to lacking further information from other

primary sources. In particular, a careful reading of The

Southern Cross, The Standard and The

Anglo-Brazilian Times is necessary for this undertaking.

The future addition of emigrant letters and family collections

to the corpus of research documentation may also include

additional records.

There is ample potential for research on the musical aspects of Irish cultural integration in Latin America and the Caribbean. The fascinating formation of the glittering music in this region has undoubtedly received its major influences from the Amerindian, African and Iberian cultures. The role of Irish music in this process, even if a very minor one, may have been underestimated.

I

hope that performers of traditional Irish music in Ireland

and in Latin America understand that imitating others’

experiences only adds una poca de gracia to the

musical cultures of both artistic communities. Certainly,

the rich musical experiences that some artists are developing

with the innovative blending of Irish and Latin American

musical arrangements may have a lasting effect on future

rhythms, melodies and harmonies.

Edmundo

Murray

Notes

*

Edmundo Murray is an independent

researcher and writer based in Geneva, Switzerland, and

a doctoral candidate at the University of Zurich. He has

been the editor of Irish Migration Studies in Latin America

(www.irlandeses.org),

and a frequent contributor to journals and publications

related to the study of the Irish Diaspora.

1

Recorded by Inchicore, “The Spirit

of Freedom”, by Derek Warfield and The Wolfe Tones.

2

The Wolfe Tones official website

(http://www.wolfetonesofficialsite.com/menu.htm),

accessed 11 May 2009.

3

Zamba (known in other

South American regions as zamacueca, cueca,

marinera and chilena) is a dance in

6/8 time originally from Peru and with African influences.

The chacarera is a fast-tempo dance alternatively

in 6/8 and 3/4 time.

4

This tango by Alberto Castillo

may be listened to at Todo Tango website (http://www.todotango.com/english/las_obras/letra.aspx?idletra=864).

5

Sound file at Todo Tango

(http://www.todotango.com/english/las_obras/letra.aspx?idletra=652).

6

Na Fianna website (http://www.nafianna.com.ar/)

7

I am thankful to Juan José Santos of University of Buenos Aires (Instituto Ravignani), for sending copies of these ballads.

References

-

Anonymous ballads published in El monitor de la campaña

(Capilla del Señor, Buenos Aires, 1872).

-

Coghlan, Eduardo A. El aporte de los irlandeses a

la formación de la nación argentina (Buenos Aires:

author’s edition, 1982).

-

Galán, Natalio. Cuba y sus sones (Valencia: Pre-Textos,

1997). First edition 1983.

-

Gargiulo, Elsa de Yanzi and Alda de Vera. Buenaventura

Luna: su vida y su canto (Buenos Aires: Senado de

la Nación, 1985).

-

Herrera, Francisco and M. Weber. Dictionnaire de la

danse (Valencia: Piles, 1995).

- López Palacio, Jorge. ‘Ma voix nomade’ in Laurent Aubert (ed.). Musiques migrantes (Geneva: Musée d’ethnographie de Genève, 2005).

-

Murray, Edmundo. Becoming irlandés: Private Narratives

of the Irish Emigration to Argentina, 1844-1912 (Buenos

Aires: Literature of Latin America, 2006).

-

Rossi, Vicente. Cosas de negros: los orígenes del

tango y otros aportes al folklore rioplatense (Buenos

Aires: Librería Hachette, 1958). First edition 1926.

-

Saavedra, Gonzalo. Interview with Astor Piazzolla, 1989,

in Piazzolla.org – The Internet Home of Astor Piazzolla

and his Tango Nuevo, website (http://www.piazzolla.org/),

cited 27 April 2009. Originally published in El Mercurio.

-

Todo Tango website (http://www.todotango.com),

cited 14 May 2009. |