Abstract

The

executed revolutionary Roger Casement continues to provoke

one of the most enduring controversies in Irish and

World history, principally because of the explicitly

sexual Black Diaries which determine both his cultural

meanings and his relevance to Anglo-Irish relations.

His investigations of crimes against humanity in the

Congo (1903) and in the Amazon (1910/11) altered the

political economy of the tropical Atlantic and inaugurated

the modern discourse of human rights. Despite efforts

to isolate his achievements and bring closure to the

debate over the Black Diaries' authenticity, Casement

continues to haunt and harangue from beyond the grave.

Ireland, it would seem, has failed Roger Casement. His

presence remains officially embarrassing and publicly

discomforting. Is it time for Latin American scholars

and writers to start to decipher his meaning and to

embrace both his history and his myth?

The

Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset begins his meditation

Man and Crisis with an essay on ‘Galileo and his effect

on History’. He invokes the image of the hieroglyph to

illustrate the idea of how, in order to see the true meaning

in the fact or the document and to reveal its deeper sense,

we must look through and beyond the hieroglyph. The fact

lies not within the fact itself, but in the indivisible

unity of everything surrounding the fact. Facts help maintain

and keep secrets, while presenting the illusion that they

are some sort of Gnostic answer to the research inquiry.

The idea has echoes in the postmodern challenge to truth

claims and the objectivity of factual reconstruction.

If the thought is extended to Roger Casement’s Black Diaries,

the researcher is confronted by a series of encrypted

hieroglyphs. Each diary is firmly chiselled on the walls

of the temple of the state’s memory, five bound volumes,

held in the National Archives (Kew, London), incontrovertible

in their physical presence. (2)

But what is revealed beneath their surface? Do they help

expose the investigation of crimes against humanity in

the Congo and Amazon that they map, or do they encrypt

and repackage meanings, emotions, secrets and truths enabling

the West to forget its trans-temporal and transnational

violations of the global South? What internal and external

dynamics are at play within the Black Diaries?

The

entangled fetish of rumour and secrecy surrounding these

documents has possessed them with a hypnotic demeaning

meaning. Their authenticity is still debated in terms

of some rather banal lines of thinking. Yet their implication

has now shifted into other contexts, where veracity can

be scrutinised in new ways. To question their authenticity

is neither a heresy nor synonymous with homophobia or

anti-statism. They can no longer be innocently upheld

as symbols of sexual emancipation, but must be interrogated

for their own internal and external logics. Using tested

critical tools to scope their deeper geographies, the

documents themselves can be surveillanced in multiple

contextual locations, their contradictions tabulated and

their dynamics read for political uses and abuses. Part

of the reason they remain so frustratingly ‘present’ is

because their interpretation and analysis has been encouraged

within an uninformed and officially restricted environment.

Thankfully, in the last decade, this has started to change

and the dynamic of the documents and the facts they contain

has shifted because of various cultural, political and

academic actions.

|

The Amazon Journal of Roger Casement

(Angus Mitchell - Anaconda Editions - 2000)

|

Nevertheless,

the Black Diaries endure as the most persistent controversy

in Anglo-Irish history in spite of the fact that they

belong within the research domains of sub-Saharan Africa

and Latin American studies. Casement continues to haunt

historical discourse like some archival phantasmagoria,

spooking official narratives of world history, subverting

certainties and challenging stereotypes. More than a dozen

monographs, biographies and edited volumes of his documents

have been published in little over a decade, along with

numerous journal articles, press reports and letters to

the editor. The controversy over the Black Diaries blunders

on like some half-forgotten history war waged on a wild

frontier of the past. (3)

Those who care, care passionately, but most people are

oblivious to either the polemic or its implications.

The

latest phase in the controversy extends from some recent

political modifications in different areas of the law

in England and Ireland, facilitating alteration in the

cultural and intellectual circumstances that had constipated

discussion about Casement and his contested Black Diaries

since the 1960s. In Britain, the Open Government Initiative

and a more transparent approach to questions of state

secrecy has precipitated a vast declassification of Casement

files, along with a different type of interrogation of

the relationship between state secrecy and state documents.

In Ireland, the Black Diaries debate was unfastened by

the changes in the Sexual Offences Act, and the decriminalisation

of homosexuality, which allowed for more open, public

discussion on these matters. Equally important was the

decision to include Sinn Féin within the democratic process.

Dissembling the barriers preventing inter-community understanding

has, however, exposed extraordinary contradictions in

conflicting historical narratives: the root cause of much

civil conflict and disobedience in the first place.

Despite

efforts to work through and reconcile the disagreements

and paradoxes exposed in the multiple inscriptions of

Casement and his representation, there survive two Roger

Casements in the historiography of twentieth-century Anglo-Irish

history. On one side, still swinging from the gallows,

is the disgraced colonial servant, who was classified

as a ‘British traitor’ and partially silenced as an imperial

agent. On the other side, buried in the archive, is the

Irish patriot, marginalised within the history of 1916

and yet still discomfortingly subversive, despite efforts

to forget him. As there was a duality in Casement’s consciousness

as a rebel Irishman serving the British Empire, so there

survives a divisive duality in his interpretation within

conflicting historical traditions. Hardly surprising therefore

that the war fought over his place in history reveals

less about the man and more about the politics of the

historical knowledge determining his reputation.

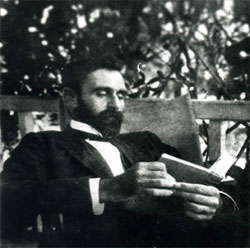

|

Roger Casement in the island of Guarujá

(Angus Mitchell - Anaconda Editions - 2000)

|

In

a cultural and political deconstruction of the man and

his facts, there are three interlinking contextual considerations

requiring scrutiny. Context, of course, is essential to

all historical representation and is susceptible to its

own inclusions, omissions, constructions and epistemologies.

The principal point of disharmony in Casement’s interpretation

is evident within the archive itself. There has been an

imaginative failure to interrogate the Black Diaries in

terms of their own archival dynamic. Why do some archives

command greater power and control over others? How and

why do specific archives privilege a narrative evident

from specific documents? How does the control of information

lead to particular distortions and imbalances in the construal

of histories? Similarly, the sexual discourse arising

from the diaries has been advantaged above all other narratives.

No one can deny Casement’s vitality in stimulating sexual

discussion, but some straightforward questions about sexual

and textual inconsistencies within the Black Diaries are

ignored and obscured. Why? A further imperative context

is revealed in the diplomatic politics of Casement’s inclusion

as a historical protagonist. Casement cuts against the

grain of agreed versions of the past, which may help explain

why he has been removed and marginalised within narratives

where he might rightly feature.

Archival

Context

The

Casement archive is both vast and fragmented. Considerable

collections of letters, papers and correspondence are

held in the National Archives (Kew, London), the National

Library of Ireland (Dublin), New York Public Library (Special

Collections) and the Politisches Archiv in Bonn. Supplementing

these collections are dozens of other smaller holdings

spread between diverse locations including the Niger Delta,

Rio de Janeiro and the palace of Tervuren, on the outskirts

of Brussels. They contain correspondence and traces that

help to build a picture of a life lived across the Atlantic

world at the height of imperial expansion in the thirty

years before the outbreak of the First World War.

Casement

was self-conscious of his place in history and the centrality

of the written word in producing both visibility and meaning.

He became a formidable constructor of history and produced

documentation that has kept him close to the discussion

on public records. How he challenged the relationship

between his versions of truth and the State’s version

is discernible from the comment made by the Under-Secretary

of State for the Home Office, Bill Deedes, in 1953, when

answering specific questions on the Black Diaries. He

commented on how governments found it ‘necessary to allow

a passage of time before uncovering the whole truth about

political events.’ (4)

In 1999 Casement files along with those of the infamous

Mata Hari were the first secret intelligence files to

be officially released into the British public domain.

(5) But by that stage

his place in history had been largely settled, or so most

people thought. (6)

In

Britain, the emphasis since the Black Diaries were released

in 1959 has been to privilege the documents as the prism

through which his life or ‘treason’ must be viewed and

understood. An example of this was made clear in 2000

when an extensive list of Casement papers was circulated

by the Public Record Office (now renamed the National

Archives): Roger Casement. Records at the Public Record

Office, which unequivocally defined the diaries as

the archival key to unlocking Casement’s meaning. (7)

Page two of the document stated that in 1959 it was intended

that they would remain closed for a hundred years, but

‘privileged access’ was allowed to ‘historians’ and ‘other

responsible persons’. It failed to mention that those

who held views contrary to that of the British State had

been excluded from seeing the documents as recently as

1990. While there is something luridly intriguing about

the Black Diaries, they are vital to unlocking information

about Casement’s two principal investigations into colonial

administration conducted in 1903 in the upper Congo and

in 1910/11 in the north-west Amazon.

At

the end of the nineteenth century, the power struggle

between European empires was primarily dependent upon

knowledge: knowledge transfigured into power and, as the

scramble for territory continued, the boundaries of knowledge

expanded: ‘[c]olonial knowledge both enabled colonial

conquest and was produced by it’. (8)

This resulted in a massive challenge of information control.

In his study of the imperial archive, Thomas Richards

has examined the value of knowledge in the organisation

of imperial order and the role of information in legitimating

imperial action. (9)

His theory builds on more familiar critiques of how knowledge

and power were constituted through cultural hegemony;

an argument advanced by Edward Said in terms of literature,

Michel Foucault in terms of sexuality and Mary Louise

Pratt in terms of travel writing. Richards builds on this

analysis and demonstrates how archives became utopian

representations of the state and instruments for territorial

control.

Yet

this knowledge empire produced its own reversals and reactions.

Richards also looks at the ‘enemy archive’: how a counter-archive,

challenging imperial matrices, extended from this early

example of a knowledge economy. He cites the publication

of the invasion novel, The Riddle of the Sands

(1903) by Erskine Childers as a key juncture in the development

of the enemy archive. It was Childers, of course, who

conspired with Casement in 1914 to run guns into Howth

in County Dublin, thereby arming the Irish Volunteers

and igniting the history of the troubles. The Casement-Childers

collaboration and their jointly hatched ‘invasion plan’

played into the deepest phobias on imperial defence and

started to interfere with the borders separating fiction

and fact.

This

mirroring of fact by fiction is constantly at play within

Casement’s life and interpretation. He deliberately constructs

his own journeys up river into the ‘heart of darkness’

– in both Africa and the Amazon – to investigate the dark

heart of ‘civilisation’ and in the trajectory of his life

there is something of both Marlow and Kurtz. The author,

Arthur Conan Doyle, bases his imperial hero, Lord John

Roxton, in his Professor Challenger novel The Lost

World, on Casement’s investigation of the Putumayo

atrocities. The borders separating fact from fiction are

crossed and re-crossed in the interpretation of Casement’s

life in a way that threatens to distort and destabilise

his facts and the official archive both from within and

without. Mario Vargas Llosa’s observation (in his interview

in this edition of IMSLA) that Casement has ‘a character

whose natural environment is a very great novel, and not

the real world’ partly explains why he remains more attractive

as a character to those who work with the imagination.

Historians, in contrast, are generally cautious of the

Casement story to the point of avoidance, a condition

resulting from the unstable and contrary nature of the

facts relevant to his story.

However,

Casement’s invasion plan to overthrow the empire ran far

deeper than the plot to train and arm the Irish Volunteers.

His lasting act of sabotage lies within the archive itself.

His investigation of King Leopold’s systemic violence

in the Congo Free State and his exposé of the City of

London’s support for Amazon rubber atrocities and, finally,

his condemnation of uncaring administration in the Connemara

district of the West of Ireland, converge into a single

atrocity across time and space. His archival legacy links

up to expose colonial abuse on a worldwide scale and systemic

failure at every turn. His archive produces a counter-knowledge

or counter-history which destabilises the architecture

of imperial knowledge through challenging the racial,

sexual and cultural norms underpinning the knowledge legitimising

imperial control.

What

lies beneath the Black Diaries (the hieroglyph) is a single

and vast trans-temporal and trans-historical atrocity

committed in the name of ‘empires’ and ‘civilisation’.

This is a crime of unspeakable dimensions that, once identified,

demands a re-periodisation of the official history of

slavery and the nineteenth century anti-slavery movement.

Casement was the chronicler of that crime at the moment

of its initiation on the Congo and during a particularly

destructive cycle of devastation defining the history

of Amazon people and their environment. His evidence of

that crime is contained in a paper trail of official reports,

letters and diaries, which become the indivisible unity

of his life leading him through the transformation from

imperialist to rebel to revolutionary. The counter-insurgent

response from the knowledge/power nexus is the deployment

of the Black Diaries, which map the key moments of his

investigations into Leopold’s Congo and British financial

complicity in the local apocalypse ignited by the Amazon

rubber industry. The Black Diaries reverse the sense and

begin the due process of distortion, reduction and confusion

by inverting Casement and turning him into the object

to be investigated: the Edwardian sex tourist preying

on the vulnerable. Thereby they break the coherency of

his transformation and recondition the facts of his life

by imposing an alternative counter-narrative to his counter-archive.

Sexuality

Context

Mrinalini

Sinha, in her work on Colonial Masculinity – The ‘manly

Englishmen’ and the ‘effeminate Bengali’ in the late

nineteenth century, demonstrates how ‘gender was an important

axis along which colonial power was constructed’ in Bengal

of the 1880s and 1890s. (10)

This same axis might be extended into Ireland up until

1916 and studied through a succession of events beginning

with the trials of Charles Stewart Parnell and Oscar Wilde,

peaking in the series of sexual scandals associated with

British administration in Dublin Castle in the Edwardian

age and ending with Casement’s trial. (11)

As the propaganda war between the British Empire and its

Irish critics deepened, so sexuality began to play a more

prominent role in how the conflict was represented for

public consumption. (12)

The power of rumour was also used with great effect as

the propaganda engagement became both more sophisticated

and more ruthless. In the background to the political

drama circulated theories on race, evolution, eugenics

and degeneration. The works of Max Nordau, Sigmund Freud,

Havelock Ellis and Richard von Krafft-Ebbing straddle

the period and helped shape thinking on and around sexuality.

George Bernard Shaw later remembered how Casement’s ‘trial

happened at a time when the writings of Sigmund Freud

had made psychopathy grotesquely fashionable. Everybody

was expected to have a secret history.’ (13)

Echoing in the background of his conviction is the humiliation

and tragedy of Oscar Wilde. Recently, Wilde and Casement

have been coupled as the sexual enfants terribles

of the Victorian and Edwardian eras.

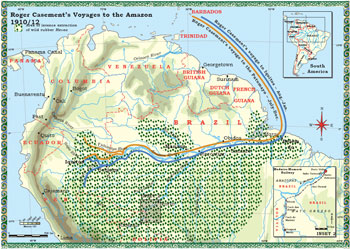

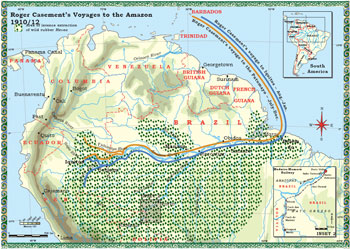

|

Roger Casement’s Voyages to the Amazon

(Matthew Stout / Sir Roger Casement's Heart

of Darkness)

|

In

the run of recent work analysing the interface between

sexuality, empire, race and gender, the Black Diaries

have been treated with some level of caution and circumspection.

Casement’s ‘gay’ status has been invoked more often as

a symbol of Irish ‘modernity’, or as a means of humiliating

intolerant attitudes amongst Irish nationalists, than

as a blueprint for ‘gay’ lifestyles. Flimsy consideration

has been given to the internal meanings of the diaries

as documents and the interpretative shadow they cast over

his investigations. Some of the reason may lie in the

often tedious style of the daily descriptions, describing

a life where mosquitoes are more visible than emotions.

To argue, therefore, that the diaries are essentially

homophobic may be unfashionable, but it is not unreasonable.

They impose various homophobic stereotypes of the ‘diseased

mind’ type and situate sexual difference in a marginal

and alienated world bereft of either love or sympathy.

Equally problematic is the treatment of the willing ‘native’

as silent and willing victim of the diarist’s predatory

instincts.

Furthermore,

the sense evident from the diaries is wildly contradictory

to how Casement made use of sexual imagery in his own

activism to build his case against colonial systems and

to provoke reaction to the plight of the colonised. What

the diaries obscure is the innovative strategy that he

adopted to challenge the gender stereotypes of his own

time and, most obviously, the hyper-masculinity so prevalent

in his era. In 1906, his colleague in the Congo Reform

Association, E. D. Morel, made a noteworthy reference

to the use of sexual abuse by the coloniser in his exposé

of the horrors wrought by the rubber industry. (14)

The comment quite probably extends from Morel’s lengthy

discussions with Casement: the source for much of his

local knowledge on Africa. He wrote how the African had

to endure:

violation

of the sanctuaries of sex, against the rape of the newly

married wife, against bestialities foul and nameless,

exotics introduced by the white man’s “civilization”

and copied by his servants in the general, purposeful

satanic crushing of body, soul and spirit in a people.

(15)

In

the explicit and vivid language used here, the linguistic

fingerprint of Casement is apparent. The general tone

of the comment, linking sexuality and colonial invasion,

is later on mirrored in his 1912 report on the Putumayo

atrocities describing horrendous abuses against Amazonian

women and children where the ‘white’ coloniser is blamed

for destroying healthy sexual lifestyles:

The

very conditions of Indian life, open and above board,

and every act of every day known to well nigh every

neighbour, precluded, I should say, very widespread

sexual immorality before the coming of the white man.

(16)

Also

integral to Casement’s subtle subversion and proto-‘queering’

of imperial gender politics was his experimentation with

new types of masculinity, which disrupted the colonial

explorer stereotype. This was a masculinity achieved without

dominance over the native and the use of the gun. Conrad

captured it when he remembered Casement in the Congo ’start[ing]

off into an unspeakable wilderness, swinging a crookhandled

stick for all weapons, with two bull-dogs: Paddy (white)

and Biddy (brindle) at his heels and a Loanda boy carrying

a bundle for all company. (17)

’ Casement’s skills at resolving conflicts in highly sensitive

situations without recourse to violence and using non-violent

and peaceful methods is contrary to his image as ‘gun-runner’

in 1914. His recruiting speeches make persistent reference

to ‘manhood’ and ‘manliness’, but idealise and encourage

the defensive and the protective use of martial force

as opposed to aggressive colonial violence.

Ireland

has no blood to give to any land, to any cause but that

of Ireland. Our duty as a Christian people is to abstain

from bloodshed …Let Irishmen and Irish boys stay in

Ireland. Their duty is clear – before God and before

man. We, as a people, have no quarrel with the German

people. (18)

Intimately

related to this recasting of Irishmen as passive and local,

as opposed to active and global, was his progressive position

on the place of women in Ireland’s move towards independence.

Women, more than men, were the enduring influence in his

life. The historian and founder of the African Society,

Alice Stopford Green, was his predominant intellectual

mentor, closely followed by the poet-activist, Alice Milligan,

the public educator, Agnes O’Farrelly, and his cousin

Gertrude Bannister. The inclusive Ireland envisaged by

Casement was one that gave equal status to all women.

In December 1907 he wrote to Agnes O’Farrelly during the

debate over the teaching of Irish at the National University:

Why

not also try to get some female representation? The

Gaelic League is largely inspired and partially directed

by women. Women played a great part in Old Ireland in

training the youthful mind and chivalry of the Gael.

(19)

When

he co-drafted the Manifesto of the Irish Volunteers,

the founding document for the movement, he deliberately

inscribed women with a role. (20)

During his trial, several newspapers commented on the

large number of women in the public gallery. But this

progressive and empathetic attitude is reconfigured and

silenced within the sexualised narrative.

A

further point of academic confusion is apparent from how

his utilisation of different gender identities has been

misinterpreted. (21)

Writing in Irish Freedom, he adopts the pseudonym Shan

van Vocht ‘Poor Old Woman’ and in some of his encoded

correspondence with the Clan na Gael he signs himself

‘Mary’. (22) When he

dies, one priest recorded how he went to the gallows with

the ‘faith & piety of an Irish peasant woman.’ (23)

Descriptions of Casement often refer to his ‘beauty’ and

his fine features using a language to portray him as if

he were a woman. (24)

In how he disrupts the colonial stereotypes of gender,

there is something of the ‘womanly man’ about Casement.

Richard Kirkland, in a comparison of Casement, Fanon and

Gandhi, acknowledged his ‘sacrifice’ as ‘part of a coherent

resistance to colonialism’ necessary in order to recreate

himself as a ‘new man.’ (25)

However, his experimentation with his own gender left

him vulnerable to interpretative control. On 17 July 1916,

the day of Casement’s appeal, the memoranda read to the

Coalition War Cabinet, which indelibly placed the diaries

on the official record, stated:

of

late years he seems to have completed the full cycle

of sexual degeneracy and from a pervert has become an

invert – a woman or pathic who derives his satisfaction

from attracting men and inducing them to use him. (26)

Few

official statements better codify the confusion over sexuality

that permeated the Coalition War Cabinet in 1916. Casement’s

treason is constructed not merely as a betrayal of his

country and his class but, above all, his gender. If there

is a single word which stands out from the transcript

of his trial it is the word ‘seduce’. Casement’s efforts

to recruit Irishmen to join his brigade in Germany, or

enlist with the Irish volunteers, are not considered as

recruitment but condemned as ‘seduction’. He is denied

the status of ‘recruiter’ and instead damned as a ‘seducer’

– a seducer of men from their loyalty to king and empire.

Obviously, the word has explicit sexual connotations.

The

Cabinet memo of 17 July can be identified as the first

queered reading of Casement in a genealogy of queer readings,

which reveal different shifts in sexual practice and politics

in both Britain and Ireland since 1916. (27)

Nevertheless, this first queered reading has required

constant renovation, restoration and sexual replastering.

In his aptly named Queer People, Basil Thomson,

the historian-policeman who discovered the diaries, spins

forgery, espionage and sexual deviancy into the world

where Casement survives as an arch protagonist. (28)

The first published edition of the Black Diaries (1959)

splices the diaries into the overarching chronicle of

the Irish independence movement between 1904 and 1922.

(29) The encrypted

message implies that Casement’s investigation of colonial

savagery was a key to achieving Irish independence, and

helps explain the presence of a photograph of Casement’s

prosecutor, the Lord Chancellor, F. E. Smith, as the frontispiece

to the volume. More recently, Jeff Dudgeon uses the Black

Diaries to update the queer geographies of Ulster and

to re-imagine Northern Protestant nationalism as some

high camp drama driven by a cabal of queer crusaders.

(30) But in each of

these re-queerings, the dismissal of the internal politics

of the diaries and how they represent the African, Amerindian,

Irish nationalist, Jew or Jamaican as willing victims

of the diarist’s desire, ignores the supremacist politics

implicit in the Black Diaries.

Casement’s

interrogation of imperial systems helped articulate unspeakable

aspects of power and inaugurated the postcolonial negotiation

of the relationship between fact and fiction, slave and

master, ‘civilization’ and the ‘primitive’. (31)

He also exposed systemic deceptions and lies controlling

the dominance of the periphery by the metropolitan centre.

His archive upturns the embedded racial and gender prejudices

inherent within colonial authority and assembles an alternative

version of events that radically transforms in the wake

of his revolutionary evolution. The defence of Casement’s

narrative remains integral to postcolonial resistance.

Conversely, the repackaging of the Black Diaries is vital

to maintaining the integrity of the archive and the historical

structures it both produces and protects.

Historian

Lynn Hunt has analysed the relationship of eroticism to

the body politic during the French revolution and shows

how the ‘sexualized body of Marie Antoinette can be read

for what it reveals about power and the connections between

public and private, revolutionary and counter-revolutionary'.

(32) If a similar approach

is taken to Casement’s archival body, then his sexuality

serves as an exceptional insight into colonial sexuality.

Beyond and beneath the hieroglyph is revealed a new man

hell-bent on overthrowing the system on multiple levels.

The response to this systemic attack is a rewriting of

his narrative in a manner designed to restore sexual normativity

and preserve imperial hierarchies while superimposing

a counter-narrative of seduction, deviancy, anti-humanism,

isolation and tropical disease to thwart accusations of

systemic violence, colonial corruption and establishment

vice. What the Black Diaries achieved through innuendo

in 1916 has been re-asserted through the authority of

‘fact’ since 1959, revealing a narrative that has succeeded

in saving both Ireland and the global South from the revolutionary

deviant.

Political

Context

In

order to understand the ‘presence’ of the Black Diaries

it is important to remember that discussion of foreign

policy was always deemed to lie beyond the control of

any potentially devolved Irish parliament. Even if Ireland

had been granted Home Rule in either 1886 or 1893, foreign

affairs would have remained within British parliamentary

jurisdiction. Nevertheless, this did not prevent the Irish

Parliamentary Party from developing a coherent critical

policy towards empire from the 1870s, which had considerable

influence on altering the wider discussion on empire and

in shaping other nationalist discourses. Irish parliamentarians

such as F. H. O’Donnell and Michael Davitt were advocates

of an international dimension to the Home Rule discussion.

What makes Casement different, however, was his acceptance

by and work for the imperial system. He was considered

part of the inner circle of the establishment and was

recognised for his services in 1911 with a knighthood.

Both of his investigations into crimes against humanity

contributed enormously to the philanthropic image of the

British Empire and to the belief in its self-regulating

capabilities.

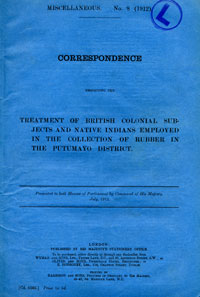

|

Putumayo Blue Book

(Angus Mitchell - Anaconda Editions - 2000)

|

The

complex political nature of those investigations reveals

both public and secret aspects of how imperial government

operated. The Congo inquiry gave Britain significant diplomatic

leverage with Belgium and also helped divert attention

away from deepening concerns about British imperial administration

in South Africa after the Boer War. In the Amazon, the

strategic publication of his reports in July 1912 persuaded

investment away from the extractive rubber economy in

the Atlantic region to the plantation rubber economy in

South-East Asia. The relevance of Casement’s 1912 Blue

Book commands greater interest in South America for

how it altered the political economy of the region than

for its validity as a document exposing the abuses carried

out against Amazonian communities. Recent global events

have disclosed once more how humanitarian intention is

often the publicly stated reason for motivating intervention,

but it often cloaks wider economic interests. The historian

Eric Hobsbawn has identified how ‘the abolition of the

slave trade was used to justify British naval power, as

human rights today are often used to justify US military

power.’ (33) The idealism

of altruism often serves as a mask for aggressive hegemonic

expansion.

This

partly explains why Casement’s official work has been

contained within layers of legislation protecting state

secrecy and security beginning with the Official Secrets

Act of 1911. As part of the inner circle at the Foreign

Office, Casement himself was bound by both the restrictions

and machinations of secrecy. Partly through that proximity

he became a stalwart opponent of ‘secret diplomacy’, a

position expressed forthrightly in his essay, The Keeper

of the Seas, written in August 1911, at the very moment

the Official Secrets Act was passing through the British

parliament. (34) His

writings published in Germany in 1915 in the Continental

Times made persistent attacks on the use and abuse

of secrecy. Casement became the most vocal and informed

critic of the secret negotiations which led to the First

World War and which he continued to condemn as undemocratic

and criminal until the noose silenced him.

|

Sir Roger Casement's Heart of

Darkness (cover)

Irish Manuscripts Commission

|

Rumours,

secrecy, silence and lies have thrived at the heart of

the Casement story and the Black Diaries have both driven

and fuelled these dynamics. Rumour was particularly destructive

at the time of his trial and helped confuse the groundswell

of support for Ireland which arose in the wake of the

execution of the leaders in early May 1916. Aspects of

secrecy are clearly at play in the negotiations of the

Irish Free State Treaty in 1921, when Casement’s solicitor,

George Gavan Duffy (the most reluctant signatory of the

treaty), faced Casement’s prosecutor, F. E. Smith, across

the negotiating table. Why Michael Collins was shown the

Black Diaries so deliberately by Smith at the House of

Lords in early 1922 and why he felt it necessary to make

a public statement about their authenticity and to open

a file on ‘Alleged Casement Diaries’ suggests that Casement

was a significant factor in the secret diplomatic negotiations

between Britain and Ireland. This may also explain why

Gavan Duffy refused to comment on the issue later in life,

when his word might have tied up so many loose ends in

the story. In 1965 Casement’s body (or, rather, a few

lime-bleached bones) were returned to Ireland at a moment

when the public discussion of the Black Diaries had reached

boiling point. After the state funeral and reburial ritual

in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin, the matter was silenced

in the corridors of Anglo-Irish diplomacy and

was judged at a political, press and academic level to

be ‘out of bounds’. By situating the story within the

confines of secret diplomacy, there is strong evidence

to suggest that the Black Diaries are part of ‘the agreed

lie’ binding British and Irish diplomatic histories of

the twentieth century.

The

critic David Lloyd has written about ‘nationalisms against

the state’ – forms of nationalism which are deemed anti-statist

and therefore unacceptable. (35)

This is why Casement remains problematic for both Irish

and British histories. He understood that Ulster was the

intrinsic keystone to Irish unity – without Ulster, Ireland

would always be compromised and truncated. His identification

with Northern Protestant Republicanism constrains him

within an historical location unacceptable to both traditions.

While being part of the consciousness of the state, he

has not been part of its written history, partly due to

the fact that he has not been contiguous with the Irish

Republic’s vision of itself. Only amongst nationalists

in the troubled north of Ireland does his name still invoke

sympathy. Furthermore, the Black Diaries have suited the

growth of a divided and modernised Ireland and a resurgent

imperial historiography. However, as documents of world

history relevant to the Congo and Amazon, they are ignored

for their own internal contradictions and prejudices and

sustained symbolically as a way of ‘discrediting the rising’

by intimating ‘that its leaders were an odd lot, psychologically

unstable, given to Anglophobia and dread homoerotic tendencies.’

(36) In Britain, they

help filter the trauma and maintain the sanctity of the

imperial image and archive.

Luke

Gibbons has commented that what the historian has to fear

is ‘history itself particularly when it is not easily

incorporated into the controlling, seamless narratives

that allow communities to smooth over, or even to deny,

their own pasts.’ (37)

Certainly, the retrieval of Roger Casement in recent years

has exposed prejudices, silences and methodological shortfalls

among Irish ‘revisionist’ historians. Where the diaries

once succeeded in closing Casement down to a point of

sexual oblivion, the situation is now reversed. They are

facilitating a flow of new critical interpretations which

conventional history is incapable of stemming. The efforts

to settle the matter of the Black Diaries ‘conclusively’,

through the flight of the academy into the safe arms of

‘science’ and the nature of these scientific conclusions

which ‘prove unequivocally...’, says more about the dilemma

in the relationship between politics and history than

it reveals anything new about the Black Diaries. (38)

The question of Casement’s sexuality is no longer at issue.

He has an essential ‘gay’ dimension which will always

be part of his own story and the meta-narrative of gay

liberation. The question now hinges on textual authenticity

which requires us to ask deeper and unsettling questions

about the authority of the archive and the role of state

secrecy in authorising knowledge. The value of the Black

Diaries as propaganda tools in the war against Irish republicanism

is over. Academics and public alike are now watching the

disintegration of an official secret or agreed lie, which

has been carried for too long through the corridors of

diplomatic negotiation. It is now up to historians and

scholars from Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa to

spearhead the next generation of Casement’s interpretation

and decipher the hieroglyph in search of their own postcolonial

past and present.

Notes

1

Angus Mitchell has lectured

on campuses in the US and Ireland and continues to publish

on the life and afterlife of Roger Casement. He lives

in Limerick.

2

Held in the National Archives

(Kew, London) as HO 161/1-5, the authenticity of the Black

Diaries has been disputed since they were first ‘discovered’

by the British authorities in 1916. They configure with

the daily movement of the British consul Roger Casement

as he made his investigation of crimes against humanity

in the Congo in 1903 and in the Amazon in 1910 and 1911.

For an account of the dispute, see Angus Mitchell (ed.)

The Amazon Journal of Roger Casement (Dublin & London,

1997) and Sir Roger Casement’s Heart of Darkness:

the 1911 Documents (Dublin, 2003). The diaries were

published in a comprehensive (and eccentric) edition by

Jeff Dudgeon (ed.), Roger Casement: The Black Diaries

with a study of his background, sexuality and Irish political

life (Belfast, 2002).

3

The most complete bibliography

is included in the biography by Seamás Ó Síochain, Roger

Casement: Imperialist Rebel, Revolutionary (Dublin,

2007) and for a brief introductory biography see Angus

Mitchell, Casement (London, 2003). The narrative

of the Putumayo atrocities is dealt with by Ovidio Lagos,

Arana rey del Caucho: Terror y Atrocidades en el Alto

Amazonas (Buenos Aires, 2005) and Jordan Goodman,

The Devil and Mr Casement (London, 2009). For

proceedings from a Roger Casement conference, held at

Royal Irish Academy in May 2000, including contributions

by various academics and independent scholars working

on different areas of Casement’s life, see Mary E. Daly

(ed.), Roger Casement in Irish and World History

(Dublin, 2005).

4

Hansard Parliamentary Debates,

3 May 1956 Vol 552 no. 174 col. 749-760. Casement’s name

was raised again during the course of the second reading

of the Public Records Bill (26 June 1967), reducing the

period for which public records are closed from fifty

to thirty years. An exception was made in the case of

papers relating to Ireland. Gerard Fitt (West Belfast)

felt it ‘of paramount importance that every consideration

should be given to the publication of all facts and circumstances

relating to the arrest, imprisonment and subsequent execution

of Sir Roger Casement.’

5

KV 2/6 – KV 2/10 – are the reference

numbers for the largely unrevealing intelligence files

declassified in 2000.

6

On issues arising from the release

of documents and the Casement debate see Angus Mitchell,

‘The Casement ‘Black Diaries’ debate, the story so far’

in History Ireland, Summer 2001.

7

On 1 December 2000 a number

of academics and archivists concerned with the Casement

debate were convened at the Public Record Office in London

where this list was circulated. It is an incomplete compilation

of files relevant to Roger Casement held at the PRO.

8

Nicholas B. Dirks (ed.), Colonialism

and Culture (Michigan, 1992) quoted by Catherine

Hall (ed.) ‘Thinking the postcolonial, thinking the empire’

in Cultures of Empire (Manchester, 2000).

9

Thomas Richards, The Imperial

Archive: Knowledge and the Fantasy of Empire (London,

1993).

10

Mrinalini Sinha, Colonial

Masculinity: The ‘manly Englishmen’ and the ‘effeminate

Bengali’ in the late nineteenth century (Manchester,

1995), p. 11.

11

The most notable of these were

the rumours circulating around the involvement of the

explorer Ernest Shackleton’s brother, Francis, in the

theft of the Crown jewels, a celebrated case used by the

advanced nationalist press against the Dublin Castle administration.

See Bulmer Hobson, Ireland Yesterday and Tomorrow

(Kerry, 1968), pp. 85-90. A recent popular biography,

John Cafferky and Kevin Hannafin, Scandal and Betrayal:

Shackleton and the Irish Crown Jewels (Dublin, 2001),

is another valuable insight.

12

See Philip Hoare, Wilde’s

Last Stand: Decadence and conspiracy and the First World

War (London, 1997). Hoare argues that war brought

into focus the threat of homosexuality and that British

intelligence was populated by men who imagined sexual

perverts and German spies going literally hand in hand.

13

Irish Press, 11 February 1937.

14

E.D. Morel, Red Rubber,

The story of the rubber slave trade flourishing on the

Congo in the year of Grace 1906 (London, 1907), p. 93-4.

15

Ibid, p. 94.

16

Sir Roger Casement’s Heart

of Darkness: the 1911 documents (Dublin, 2003), pp.

182-3.

17

C.T. Watts (ed.) Joseph Conrad’s letters to Cunninghame

Graham (Cambridge, 1969), p. 149.

18

Irish Independent, 5 October

1914.

19

Roger McHugh Papers, National

Library of Ireland MS 31723, Roger Casement to Agnes O’Farrelly.

19 December 1907.

20

Bulmer Hobson, A Short History

of the Irish Volunteers (Dublin, 1918), p. 23: ‘There

will also be work for women to do, and there are signs

that the women of Ireland, true to their record, are especially

enthusiastic for the success of the Irish Volunteers.’

21

See Lucy McDiarmid, ‘The Posthumous

Life of Roger Casement’ in A. Bradley and M. Gialanella

Valiulis (eds.) Gender and Sexuality in modern Ireland

(Amherst, 1997). McDiarmid argues that Casement’s

‘camp locutions’ in his letter of 28 October 1914 might

be compared to ‘deliberately girlish utterances of a faux-homosexual

voice.’ The fact that Casement was leading a revolution

and was under close surveillance does not strike McDiarmid

as a valid alternative explanation for his encoded communications.

22

Reinhard R. Doerries, Prelude

to the Easter Rising: Sir Roger Casement in Imperial Germany

(London, 2000) 49. Casement addresses a letter to Joseph

McGarrity ‘Dear Sister’ and signs it ‘Your fond sister,

Mary’.

23

Archives of the Irish College,

Rome. Papers of Monsignor Michael O’Riordan Box 17. Thomas

Casey to O’Riordan, 3 August 1916.

24

Stephen Gwynn, Experiences

of a Literary Man (London, 1926) 260, refers to Casement’s

‘personal charm and beauty … Figure and face, he seemed

to me then one of the finest-looking creatures I have

ever seen.’

25

Richard Kirkland, ‘Frantz Fanon,

Roger Casement and Colonial Commitment’, in Glenn Hooper

& Colin Graham (eds.) Irish and Postcolonial Writing;

History, Theory Practice (London, 2002).

26

TNA, HO 144/1636/311643/52 and

53

27

Efforts to place his meaning

and that of the diaries into the narrative of gay history

was recently undertaken by Brian Lewis, ‘The Queer Life

and Afterlife of Roger Casement’, Journal of the History

of Sexuality, vol. 14, No. 4, October 2005, 363-382.

However, the analysis avoids any deep reading of the documents,

or reference to the recent discussions on the relationship

between propaganda and intelligence.

28

Basil Thomson, Queer People

(London, 1922), p. 91: ‘Casement struck me as one of those

men who are born with a strong strain of the feminine

in their character. He was greedy for approbation, and

he had the quick intuition of a woman as to the effect

he was making on the people around him.’

29

Peter Singleton-Gates and Maurice

Girodias (eds.) The Black Diaries, An account of Roger

Casement’s life and times with a collection of his diaries

and public writings (Paris, 1959).

30

Jeff Dudgeon (ed.), Roger Casement: The Black Diaries with a study of his background,

sexuality and Irish political life (Belfast, 2002)

31

It is interesting to note that

Robert J.C. Young begins his study of Postcolonialism:

an historical introduction (Oxford, 2001) with Casement

emerging from the Amazon in 1910.

32

Lynn Hunt (ed.), Eroticism

and the Body Politic (Baltimore, 1990).

33

Eric Hobsbawm, ‘America’s imperial

delusion’, in The Guardian 14 June 2003 reprinted

from Le Monde Diplomatique (June 2003).

34

Sir Roger Casement’s Heart

of Darkness, pp. 556-66. Casement’s other important

essay The Secret Diplomacy of England, published

posthumously in The Irishman (9/3/1918) and reprinted

in the Royal Irish Academy, Roger Casement in Irish

and World History (Dublin, 2000) programme for the

symposium. Among recent accounts on secrecy and the British

state, see David Vincent, The Culture of Secrecy –

Britain 1832-1998 (Oxford, 1998).

35

David Lloyd, Ireland after

History (Cork, 1999), pp. 19-36.

36

Seamus Deane, ‘Wherever Green

is read’ in Máirín Ní Dhonnchadha and Theo Dorgan (eds)

Revising the Rising (Dublin, 1991), p. 100.

37

Luke Gibbons, Transformations

in Irish Culture (Dublin, 1996), p. 17.

38

Mary E. Daly (ed.), Roger

Casement in Irish and World History (Dublin, 2005)

contains a selection of the internal handwriting comparisons

carried out on the diaries.

References

- Cafferky, John and Kevin Hannafin, Scandal and Betrayal: Shackleton and the Irish Crown Jewels (Dublin: The Collins Press, 2001).

- Casement, Roger, ‘The Secret Diplomacy of England’ in Royal Irish Academy, Roger Casement in Irish and World History (Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 2000).

- Daly, Mary E. (ed.), Roger Casement in Irish and World History (Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 2005).

- Deane, Seamus, ‘Wherever Green is read’ in Máirín Ní Dhonnchadha and Theo Dorgan (eds) Revising the Rising (Dublin: Field Day, 1991), pp.95-105.

- Doerries, Reinhard R., Prelude to the Easter Rising: Sir Roger Casement in Imperial Germany (London: Irish Academic Press, 2000).

- Dudgeon, Jeff (ed.), Roger Casement: The Black Diaries with a study of his background, sexuality and Irish political life (Belfast: Belfast Press, 2002).

- Gibbons, Luke, Transformations in Irish Culture (Dublin: Cork University Press 1996), p. 17.

- Goodman, Jordan, The Devil and Mr Casement (London: Verso, 2009).

-

Gwynn, Stephen, Experiences of a Literary Man

(London: Thornton Butterworth, 1926), p. 260.

- Hall, Catherine (ed.), ‘Thinking the postcolonial, thinking the empire’ in Cultures of Empire (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000)

- Hansard Parliamentary Debates, 3 May 1956 Vol 552 no. 174.

- Hoare, Philip, Wilde’s Last Stand: Decadence and conspiracy and the First World War (London: Arcade Publishing,1997)

- Hobsbawm, Eric, ‘America’s imperial delusion’, in The Guardian (London) 14 June 2003, p. 16.

- Hobson, Bulmer, Ireland Yesterday and Tomorrow (Kerry: Anvil Books, 1968), pp. 85-90.

- Hunt, Lynn (ed.), Eroticism and the Body Politic (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1990).

- Kirkland, Richard, ‘Frantz Fanon, Roger Casement and Colonial Commitment’, in Glenn Hooper & Colin Graham (eds.), Irish and Postcolonial Writing; History, Theory, Practice (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2002)

- Lagos, Ovidio, Arana Rey del Caucho: Terror y Atrocidades en el Alto Amazonas (Buenos Aires: Emecé, 2005).

- Lewis, Brian, ‘The Queer Life and Afterlife of Roger Casement’, Journal of the History of Sexuality, (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press) 14: 4 (October 2005), pp. 363-382.

- Lloyd, David, Ireland after History (Cork: Cork University Press, 1999).

- McDiarmid, Lucy, ‘The Posthumous Life of Roger Casement’ in A. Bradley and M. Gialanella Valiulis (eds.), Gender and Sexuality in Modern Ireland (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press,1997).

- Mitchell, Angus (ed.) The Amazon Journal of Roger Casement (Dublin: Lilliput Press & London: Anaconda Editions, 1997).

- __________, Sir Roger Casement’s Heart of Darkness: the 1911 Documents (Dublin: Irish Manuscripts Commission, 2003).

- ___________. Casement. (London: Haus, 2003).

- ¬¬___________, ‘The Casement “Black Diaries” debate, the story so far’, History Ireland, Summer 2001: 42-45 http://www.historyireland.com//volumes/volume9/issue2/features/?id=113555

- Morel, E.D., Red Rubber, The story of the rubber slave trade flourishing on the Congo in the year of Grace 1906 (London: Fisher Unwin,1907), pp. 93-4.

- Singleton-Gates, Peter and Maurice Girodias (eds.), The Black Diaries, An account of Roger Casement’s life and times with a collection of his diaries and public writings (Paris: Olympia Press, 1959).

- Sinha, Mrinalini, Colonial Masculinity: The ‘manly Englishmen’ and the ‘effeminate Bengali’ in the late nineteenth century (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995).

- Ó Síochain, Seamás, Roger Casement: Imperialist Rebel, Revolutionary (Dublin: Lilliput Press, 2007).

Richards, Thomas, The Imperial Archive: Knowledge and the Fantasy of Empire (London: Verso, 1993).

- Thomson, Basil, Queer People (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1922).

- Vincent, David, The Culture of Secrecy: Britain 1832-1998 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).

- Watts, C.T. (ed.), Joseph Conrad’s letters to Cunninghame Graham (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969).

- Young, Robert J.C., Postcolonialism: an historical introduction (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2001).

|