|

More importantly, a close look at these two countries

serves to dismiss some of the claims of a well-known

globalisation thesis, according to which sustained economic

growth can only be attained through opening spaces for market

competition and removing barriers to the free movement of the

factors of production, including protection of employees. Even

though I will show how the opening of the two economies to

inflows of capital and labour has been critical to achieving

higher growth levels, these processes have been managed,

albeit in different ways and to different extents, through the

mechanism of social dialogue between trade unions, employers,

civil society actors and the state. The Spanish and Irish

experiences hence show that there are benefits to cooperation

and that globalisation cannot necessarily be reduced to a

zero-sum game. In the following paragraphs I will explore the

three ingredients for growth and will discuss their role in

the two countries. Finally, I will discuss some of the

problems that lie ahead and will stress the need to search for

innovative solutions within the consensual framework of

national social dialogue in order to manage the challenges

posed by global competition and migration.

The keys to

success:

1. Social Pacts and Concertation

According to some of the more enthusiastic supporters

of globalisation, this process is changing the shape of the

world as national governments are losing their capacity to

manage their economies autonomously. The increasingly

interconnected character of economic and social activities as

well as the significant role of multinational corporations,

the argument follows, are imposing binding constraints upon

the set of policies available to national actors. As a

consequence, governments are powerless, and are forced to

adopt a market logic in the design of their economic policies

in order to suit the demands and preferences of mobile

capital. The corollary of this trend is the extension of

neo-liberal economic policies that according to the so-called

Washington Consensus developed in the 1980s, deliver higher

economic growth and employment rates, though at the cost of an

increase in social and economic inequalities. More

specifically, by forcing the de-regulation of labour markets

and cuts in social policies, capital will be able to increase

profits at the expense of increasingly lower levels of

protection for employees.

The success stories of the Irish and Spanish economies

in the past fifteen years however show that there are ‘third

ways’ to achieve growth in addition to the neo-liberal one. As

a matter of fact, developments in these two countries portray

a very different picture to the one suggested by the

neo-liberal path and the hyper-globalist thesis. Hence, rather

than simply giving in to the pure market demands of

transnational capital, both the Spanish and Irish government

have engaged during the last twenty years in processes of

tripartite social dialogue with trade unions and employer

organisations whereby they have – rather successfully judging

by their results - managed external pressures through domestic

processes of consultation, concertation and social pacts. The

first objective of these processes has been to achieve

macroeconomic stability through wage moderation and the

negotiation of cuts in the welfare state. The second main

objective has been to introduce structural reforms in the

economy aimed at enhancing their growth and employment

potential. Finally, these agreements have also tried to

re-distribute the benefits derived from economic growth.

|

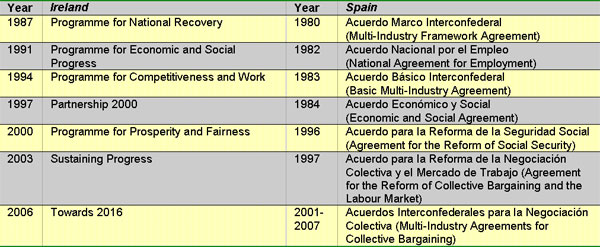

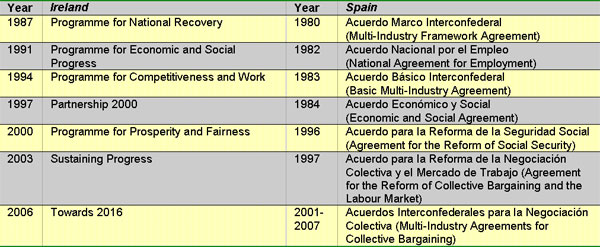

Table 1: Social Pacts and Partnership Agreements in

Ireland and Spain |

Table 1

shows the most important steps in social dialogue in the last

twenty years. The experience of national tripartite social

dialogue was initiated in Spain in the late 1970s and early

1980s in the context of the country’s transition to democracy.

It has been argued that a strategy of consensus with all the

relevant social and political actors became the cornerstone

for a successful political transition. However, social pacts

in these years also had an important economic role, as the

Spanish economy only started to suffer from the full effects

of first oil crisis in the late 1970s. Accordingly, the social

pacts served to find negotiated or consensual solutions to a

situation of political, economic and social emergency. From a

political perspective, social pacts served to show the strong

determination of all social and political forces to

consolidate democracy in Spain after more than three decades

of dictatorship. The political role of social pacts became

particularly clear in 1983 when a new agreement was signed

right after a failed coup d’etat. However, the most

visible contribution of social pacts and tripartite agreements

was to economic stability. Even though these pacts covered a

large number of issues ranging from social policy to union

recognition and the labour market, the central theme to all of

them was the reduction of inflation through wage restraint and

changes in wage setting mechanisms. |