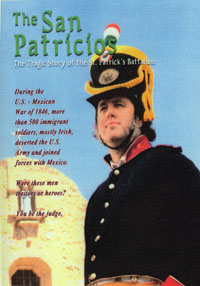

|

When this documentary was first released, the San Patricios

were a much-neglected aspect of Irish American history and the

history of the Americas generally. During the ensuing decade, they

have received a great deal of attention both with the

publication of books and with other documentaries, one of which was

shown at the national meeting of the American Conference for

Irish Studies in St. Louis, Missouri, in April 2006. At least some of the

credit for rescuing the San Patricios from neglect must go to

Mark Day.

The story of the San Patricios is deceptively

straightforward. A group of Irish immigrants who were serving

in the

United States

army deserted and formed a unit in the Mexican army that

fought against the United States during the war with Mexico. Some

had deserted before the war began, - as it turned out, a

salient point - and others after the war began. The generally

harsh treatment of enlisted men in the

US

army at the time and discrimination against Irish Catholics

were factors in their desertion - all accounts agree on this

point. When United States forces captured them, those who had

deserted after the war began were hung in an especially cold

and calculated way. The leader of the San Patricios, John

Riley, was from Galway and had worked on Mackinac Island,

Michigan before enlisting in the army. There is not much

disagreement on any of these issues.

Where things begin to diverge is in how the San Patricios

are viewed. The documentary makes the point that they are

honoured in Mexico as heroes who fought and died for Mexico. A

memorial was unveiled in Ireland honouring them while the

documentary was being made. In the United States, they are often

seen as traitors - when their existence is acknowledged at all.

For many years, the US army apparently denied that the incident had

ever happened. Clearly, the incident happened. We can debate

why the US army would deny it. The motivations of the

individuals in the unit for their decision, especially those

of their

leader John Riley; the motivation behind their harsh

punishment; and what, if anything, the incident tells us about

the position of the Irish in the United States, together with a range of

other historical questions, are less straight forward and are subject to speculation and debate. Like many immigrants, the

individual San Patricios left little behind with which to study their motivations and thoughts.

However, the real question in this review is:

how effectively

does The San Patricios: The Tragic Story of the St.

Patrick's Battalion tell its story? The answer is

neither simple nor straightforward. The production values

generally are first-rate. This is a well-executed, professional

piece of work without question or quibble. It is sharp, clear,

in focus at all times, unlike another documentary on the same topic

that I had seen. There are still too many historical

documentaries that do not have

these basic qualities. There is a nice mix of period graphics,

scholars offering facts and interpretations, and footage of

battle and other reenactments that are quite well done. Visually this

is a successful production. The documentary also has a clear

argument that organises the information presented and

structures the presentation.

With the exception of

Kerby Miller,

the 'expert scholars' are not especially impressive. One,

Rodolfo Acuña, seems to have a political agenda to champion

rather than a historical interpretation to present and

journalist Peter Stevens does not appear to know much about

scholarship on Irish migration to the US, even allowing for

the fact that

the programme is ten years old, or much beyond the handed-down,

popular history of the Irish in America. This raises questions

about the point of the presentation - is it intended to explore a

little-known episode in

US

history or is there a political agenda of accentuating the

racism of United States society and past discrimination against

Irish Americans, and even of supporting Mexican groups seeking to

regain the territory lost in the war between the two countries? Neither Acuña nor Stevens provides much of

historical substance nor shows any evidence of a deep knowledge

of the incident itself, US military history, or the history of

Irish migration to the US. Having an opinion is one thing,

having an opinion based on familiarity with the relevant

primary source materials and scholarship is another.

There are other problems. Riley is an elusive figure and

little can be said about him with certainty. The examination

of his character is probably

handled as well as it might be, although the uncertainties

undermine a solid acceptance of the thesis advanced. More

troubling is the confused way in which the history of Irish

migration to the United States is presented. Many of the

graphics used to illustrate life in Ireland date from after

the period when Riley and the other San Patricios left. They do not

show their Ireland, but a later, post-famine Ireland that was

markedly different. The entire discussion of Irish emigration

to the United States is confused at best, especially as it

relates to the war between Mexico and the United States. Kerby Miller tries to sort it out,

but the other experts do not seem to have the chronology clear

in their own minds. The discussion of the idea of Manifest

Destiny in the United States is weak, especially in relation

to the issue of slavery. Since it was a critical factor in the

war, it should be more fully and clearly developed. There are

other issues, mostly small ones that could be raised.

Despite these problems, the programme succeeds, to a

considerable extent, in achieving its goals. The San Patricios

are portrayed in a sympathetic light and the brutality of

their treatment is clear. It sustains interest throughout

because of its technical excellence. In raising questions

and making the viewer engage with the topic and seriously weigh the

material presented, even if in disagreement, it has accomplished a

great deal. As a testament to the significance of the

documentary, I will be using it in my military history course

because its perspective needs to be considered seriously and

the issues it raises discussed.

William H. Mulligan, Jr.

* Ph.D., Professor of History, Murray State University, Murray,

Kentucky, USA

Author's Reply

I would

like to thank Dr. Mulligan for his kind remarks about the

San Patricios documentary, especially his reference to the

film's production values as first rate.

I would

also like to thank him for his scholarly analysis of the

documentary's treatment of Irish immigrants, the unjust US

intervention in Mexico of 1847 and the doctrine of Manifest

Destiny that to this day influences US foreign policy. This is

exactly the kind of discussion that I hoped this documentary

would spark. The purpose of all historical texts should be

reflection on times past and how they speak to us in the

present. In that spirit, I would like to share some of my

thoughts regarding the ideas expressed in his review.

Mulligan

asks: 'Is it intended [my documentary] to explore a little

known episode in US history, or is there a political agenda of

accentuating the racism of US society and past discrimination

against Irish Americans, and even of supporting Mexican groups

seeking to regain the territory lost in the war between the

two countries?' In other words, does Mark Day have a political

agenda, a specific point of view, a bias? Yes, of course.

Everyone operates from his/her particular bias. To deny bias

becomes an agenda in itself. There is no such thing as 'pure'

history. Historical facts are interpreted. And those

interpretations are themselves historically contingent.

The most

commonly recounted history of the US, from the genocidal

treatment of Native Americans through slavery and on to the

military conquest of Mexico, has been the grand narrative

written by the victors, not the losers. One of the chief

spoils of conquest and colonisation is the power to tell the

stories of history. Traditionally, these storytellers are, for

the most part, white, conservative and middle-aged men who

believe the lens through which they interpret the world is

pure and unbiased. In other words, the normalising gaze of

power hides the reality that history is always told through an

ideological lens. The question that I believe to be most

important is: Who benefits from this interpretation of

historical facts? Not to do so belies a cultural blind spot, a

blind spot born of the privilege of power.

So instead

of stories about resistance from Native Americans and the

rebellions of slaves, we learn about the exploits of

presidents and generals. Instead of life and death struggles

of workers and trade unions, we are told about wealthy bankers

and the golden ages of industry and commerce. And instead of

learning about the humiliation of Mexico with the Treaty of

Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, we are regaled with stories about

the rugged individuals who tamed the West. We learn about

History with a capital 'H,' but very little about the

histories of the people who shaped and were affected by the

onward rush of events. We seldom learn about history told from

the bottom up.

Historian

Howard Zinn points out some examples of this historical

amnesia. He writes about the glorification of Christopher

Columbus as a man of skill and courage, but the omission of

criticisms from contemporaries such as Fray Bartolomé de las

Casas. The latter writes of Columbus: 'The admiral was so

anxious to please the King that he committed irreparable

crimes against the Indians' (Zinn 1990: 57).

Zinn also

mentions historians' omission of the Ludlow massacre of

miners' wives and children by the Colorado National Guard in

1913. He suggests that it might be considered 'bold, radical,

or even communist' to talk about these class struggles in a

nation that prides itself on the oneness of its people. And

where, he wonders, are the stories about the abolitionists,

labour leaders, radicals and feminists? Zinn writes that the

'pollution of history' happens not by design, but when

scholars are afraid to stick their necks out, and instead play

it safe (Zinn 1990: 62; Zinn 2003). This provides strong

evidence that the project of history itself is inherently

political.

This is

why the story of the San Patricios always intrigued me. I

first learned about this motley band of mostly Irish renegades

from César Chávez when I worked as an organiser with the

United Farm Workers Union in the late sixties. But it was due

to the scholarly work of Robert Ryal Miller and his book,

Shamrock and Sword (University of Oklahoma Press, 1989),

that I discovered the story behind the battalion, formed by

Irish immigrants in the Mexican army. Later, working on the

film put me in contact with several Mexican scholars and

ordinary citizens who saw the story from a totally different

angle, from the viewpoint of the conquered, the vanquished. I

also spoke with experts on nativism in mid-nineteenth century

America.

This leads

to another question. Are there parallels in the nativist

attacks against the Irish in US history and the resurgence of

nativism against Mexican and Latin American immigrants today?

I would suggest that parallels are to be found in the tendency

to exploit and scapegoat newcomers, the shared colonial

experience and Catholic faith, the crude stereotypes applied

to both groups, and the perceived threats of immigrants to the

job market and American culture, to name a few. The

similarities in nativist rhetoric from that period are so

closely related to the current situation that you can simply

remove the word 'Irish' and replace it with 'Mexican'. Few

people today would recognise the difference. But I did not

make this documentary to accentuate nativism and racism. These

realities come forth because they were endemic to that period,

much to the dismay of those who would like to downplay them

for ideological reasons.

Lastly,

was the intent of the San Patricios documentary to support

those who wish to regain the territory that Mexico lost with

the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo? Hardly. Aside from

commentator Lou Dobbs of CNN and his nightly nativism, the

only people talking about the so called reconquista or

re-conquest of the Southwest are fringe groups like the

Minutemen vigilantes and Pat Buchanan, who attract a miniscule

following among ordinary US Americans. Most Mexican-Americans

and Mexican immigrants, like their nineteenth-century Irish

counterparts, simply want what most US Americans seek - to

live in peace, to work hard and to be accepted, like everyone

else. In short, they are seeking the US American dream. It has

been gratifying to witness the lively discussions at the

screenings of the San Patricios, to watch the interchanges

between disparate groups of people, and to get feedback from

students and professors who have benefited from the film. If

it advances understanding about Irish immigrants in the

nineteenth century and the situation in Mexico, then and

today, I am more than satisfied.

Mark R.

Day

Vista,

California

References

- Zinn,

Howard. Declarations of

Independence

(New York: Harper Collins, 1990), 57.

- Ibid.,

62. See also Howard Zinn's People's History of the

United

States

(New York:

Harper Collins, 2003). |