The Irish Road to South America Nineteenth-Century Travel Patterns from Ireland to the River Plate |

|||||||||||

Page

8 |

|||||||||||

|

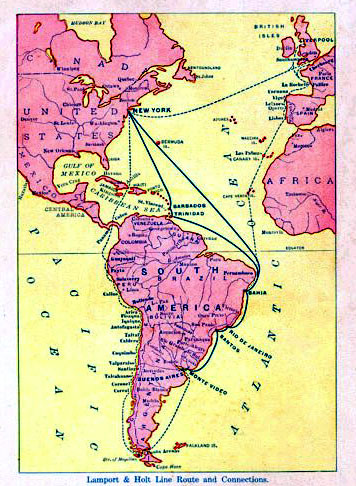

Before the 1880s, the most important ship in terms

of quantity of Irish emigrants was La Zingara, the smallest vessel

of Thomas B. Royden & Co fleet. She was built in 1860, in Liverpool,

and was registered in the Lloyd’s Register of British and

Foreign Shipping in 1861. The rigging was a barque, sheathed in

yellow metal in 1860, fastened with copper bolts (287 tons). The

captain was George Sanders. John Murphy remarks that 'passages on

La Zingara are cheaper than other vessels like the Raymond from

Dublin (Captain Lenders)' [Murphy to Murphy 1864].

The SS Dresden was the ship that carried ‘the largest number of passengers ever to arrive in Argentina from any one destination on any one vessel’ [Geraghty 1999]. This event was the outcome of a deceitful immigration scheme managed by the Argentine government agents in Ireland Buckley O’Meara and John Stephen Dillon, a brother of Fr. Patrick J. Dillon, founder The Southern Cross, National Deputy for Buenos Aires, and notorious leader of the Irish-Argentine community. The affair ‘became infamous and was denounced in Parliament, press and pulpit’ [Geraghty 1999]. These emigrants came from poor urban areas of Dublin, Cork and Limerick and most of the adults were city labourers and servants. Upon arrival, some were assisted by Irish-Argentine families well established in the country or found jobs in Buenos Aires, but most of them were deceived by unscrupulous agents and were abandoned in remote areas. Paradoxically, some of the emigrants (especially children) died in Argentina of hunger and related illnesses, which were typical of the miserable situation they left in Ireland. The bad press got by this sad events was enough to stop the Irish emigration to Argentina almost completely for some decades The

SS Dresden arrived at Buenos Aires from Queenstown (now Cobh)

and Southampton on 15 February 1889, with 1,772 passengers on board.

According to their only friend, Fr. Gaughran, they |

|||||||||||

were

allowed to land on Saturday when the authorities well knew there

was no accommodation for them. Many hundreds of these poor people

had not received orders for the [Immigrants] hotel before leaving

the ship, and weary hours were spent in the struggle to get to the

table where these orders were issued. Then, the orders obtained,

strong men could fight their way through the throng of Italians

[who arrived the same day in the Duchesa di Genova] into the dining

hall, but the weak, the women and children were left supperless.

It was soon evident that unless some special arrangements were made

even the shelter of a roof could not be obtained […]. Men,

women and children, hungry and exhausted after the fatigues of the

day, had to sleep at best they might on the flags of the court-yard.

To say they were treated like cattle would at least provide them

with food and drink, but these poor people were left to live or

die unaided by the officials who are paid to look after them, and

without the slightest sign of sympathy from these officials. I am

told that as a result a child died during the night of exhaustion.

In England those responsible would be prosecuted for manslaughter,

but in this land of liberty no one minds’ [Murray 1919: 443-444].

|

|

||||||||||

| The

British chargé d'affairs in Buenos Aires, George Jenner,

reported that ‘the Argentine officers are mainly responsible

for the mismanagement of the Irish immigration. Their offices in

Ireland have, in more than one instance, allowed the propaganda

for emigrants to fall into the hands of totally untrustworthy persons,

who have recruited numbers of worthless characters, including prostitutes

and beggars, and many shiftless individuals and families utterly

unfit to carry on the struggle for existence in the Argentine Republic’

[Jenner to Salisbury, 21 February 1889].

Due to bad press created by the Dresden Affair and to the financial crisis of 1890, during the last decades of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth century, relatively few Irish emigrants selected Argentina as their final destination. In the 1920s, there was yet a new peak of arrivals from Ireland (76% of 1900-1929 Ireland-born passengers arrived in the 20s), in which the majority of immigrants were educated urban professionals, with a high proportion of Church of Ireland religion. This increase may have been a consequence of political, social, and economic turmoil in Ireland. However, it ended in late 1929, as a consequence of the global financial crisis that seriously affected economic growth and employment rates of Argentina and other countries. By this time, the sheep-farming opportunities of the 1840-80s decreased due to changes in the international markets, in which cattle and cereal became the increasingly dominant agriculture export. Irish-Argentine estancieros began hiring immigrants of other origins, particularly from Italy, as tenants to till their land. At the same time, Irish-Argentine families joined the urban bourgeoisie of Buenos Aires and other cities in an unique acculturation process that would last until the 1982 Falklands/Malvinas War between England and Argentina. As a result of social and economic factors, migration flow changed its direction and is today increasingly growing from Argentina to Europe and the United States. At the present time, it is reported that some of the Argentine descendants of Irish immigrants are re-emigrating to Ireland. However, with the remarkable changes in the intercontinental journey after the World War II, their major struggle will be to obtain work permits in Ireland. Conclusion |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

This

article explored some material aspects of the transportation used

by the emigrants. Other findings await the researcher of the Irish

emigration to Argentina. For instance, the pioneering work done

by Coghlan (1982) in establishing a data base of almost five thousand

passengers for genealogical purposes has not been exhaustively integrated

into any further cultural-historical study. Other passenger lists,

for instance, CEMLA database (Centro de Estudios Migratorios Latinoamericanos),

add up to seven thousand passengers. These lists could be explored

with a focus on relations among passengers, including kinship, friendship,

class, gender, and religion. I would suggest that we should attend

to the material and social nexus that supported the traffic in immigration

in order to disclose a few of the pertinent experiential features

of the emigrant’s world. |

|||||||||||

| The Society for Irish Latin American Studies |

Copyright Information |

|