This

revised English version of the author’s 2004 Devenir

Irlandés offers some advantages over the original

Spanish edition. It abridges some of the documents that make

up the bulk of the volume: two memoirs and two sets of

family letters from Irish immigrants in Argentina, without

losing any substance. The documents are now presented in

their original language. Murray has also added a fuller

discussion of the notion, conveyed in the title of the book,

that social identities represent processes rather than fixed

entities.

In this

becoming or devenir, Murray identifies three stages

that defy linear concepts of assimilation. Early arrivals

were identified generically as English and seem to have done

little to contest the rubric. Murray’s contention that they

came to “an informal colony of the British Empire in which

everything, except probably meat and hide came from the

British Isles” is — perhaps intentionally — exaggerated.

Fashion and elite culture, from architectural styles to

literary forms, were more likely to originate from

continental Europe than from England. Most immigrants came

from Italy and Spain, as did deeper cultural traits ranging

from language and music to pasta and anarchism. Yet beneath

the hyperbole, there is a valid point. The Irish may not

have exactly evolved “from colonized to colonizers,” but

Argentina’s ethno-racial totem pole supplied new material

for identity construction.

|

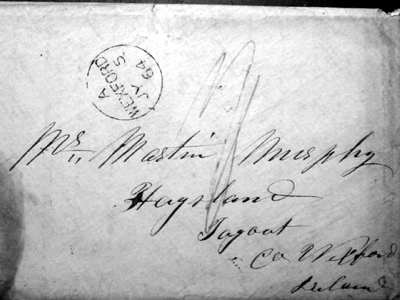

Letter from John Murphy (Salto, Buenos

Aires) to Martin Murphy received 5 July 1864

(Anastasia Joyce Collection) |

Being

white, Northern European, and British provided status

building blocks not available to, say, their compatriots in

Liverpool. The label of “backwardness” was pinned at the

time on the native inhabitants of the Pampas rather than on

the newcomers. Catholicism was not a marker of religious and

moral depravity in Buenos Aires. The second stage in this

process of becoming coincides with a surge of cultural

nationalism, bordering on nativism, among

early-twentieth-century Argentine elites. The former

“ingleses” now accentuated their Argentineness: their

connection to the land, to pastoral activities and to the

gaucho (favoured emblems of nationhood), to military,

patriotic rituals, and apparently to Catholicism. Unlike in

most other Latin American countries, Catholicism was a

particular accoutrement of nationalism in Argentina.

Ultimately, they find themselves “becoming irlandés.”

Argentina’s socio-economic decline and Ireland’s rising

fortunes have promoted a revival of what used to be called

in the 1970s “symbolic ethnicity,” that includes conspicuous

St. Patrick’s Day celebrations, decorative shamrocks, and

the replacement of “mate and bizcochitos” with tea and

scones.

A

demographic portrayal of the Irish community is subsequently

offered. Murray calculates that between forty and fifty

thousand Irish came to the River Plate during the century

following 1830. About half of these returned to Ireland or

moved to other countries, particularly the United States;

and about half of those who stayed in Argentina died in

epidemics — a mortality estimate that seems abnormally high.

The county of Westmeath supplied 43 per cent of the exodus,

and Wexford and Longford some 15 percent each. Like

emigrants almost everywhere else, these were young people,

with an average age of twenty-four. Only 15-17% of them

remained in the Argentine capital, probably the lowest urban

concentration among all immigrant groups in the country. The

majority settled in the province of Buenos Aires, with some

later moving to Santa Fe, and engaged predominantly in

pastoral activities. Men outnumbered women three to one

before 1852. One would imagine that the ratio decreased

later because, in general, the female proportion tends to

increase as migration flows mature, and Irish emigration in

general had a higher female ratio than those of most other

contemporary flows. Whatever their gender, few, if any,

spoke Irish as a first language: there is not a single

Gaelic word in the documents other than place names.

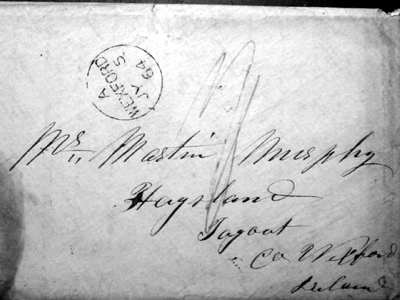

|

John Murphy's estancia La Flor del

Uncalito, Salto |

The

documents, of course, may not be entirely representative. As

Murray notes, the family papers that survive tend to be

those that families consider important, normally meaning

that they present the family’s history in a positive light.

Positive or not, the documents here shed much light on the

process of migration from the bottom up. Edward Robbins’

memoirs basically list, chronologically, family events: an

uncle’s military campaign with Simón Bolívar in 1819 and his

death soon after in Bolivia, the building of a farm house

back home, the birth of children and death of parents, the

emigration of thirteen family members to Argentina in 1849,

rural work, business deals and so on. The letters to the

Murphy family in Wexford start from Liverpool in 1844 with

the promise that others would arrive as soon as the ship

docked in Buenos Aires. However the first letter from

Argentina in the volume comes nine years later, perhaps

because early correspondence was not preserved. This

collection is particularly illuminating of the immigrant

experience. It includes requests for pre-paid passages and

remittances, observations about foreigners’ lack of

involvement in local politics, descriptions of the workings

of a sheep farm, news of the Paraguayan War, details about

family feuds and duties, and the assertion that Argentina is

not “a half civilized, half savage desert wilderness such as

we read in Sin-Bad the Sailor and other like fairy tales,”

but a sophisticated country with greater opportunities than

Ireland. The third collection includes letters from three

young women in Buenos Aires to their relative John James

Pettit, who had been born there in 1841, ten years after his

parents had arrived from Ireland, but moved to Australia

with his son in 1852. The last document, as the first, is a

memoir but written much later (in the 1920s), and in a more

literary style, by a third-generation Irish-Argentine who

remembered, among many other delightful tidbits, a creole

gaucho who “spoke English with as good a brogue as any

Irishman." That this writer was born in 1864 and was the

grandson of immigrants highlights the pioneering role that

the Irish - along with the Basques - played in Argentine

immigration and the settling of the Pampas.

This,

however, is not a book written in the hagiographic genre of

“immigrant contributions.” It does not celebrate great deeds

and exceptional accomplishments. It does something more

difficult and intellectually satisfying. It rescues from

obscurity the stories of people who toiled, lived, loved,

and dreamt beyond the spotlight of official histories. These

are stories of everyday life, of home, as Murray’s

interesting discourse analysis demonstrates, rather than

nation. Yet these seemingly mundane narratives are often

more captivating than national epics and, in their

simplicity, at times poetic. Murray’s introduction,

epilogue, and notes place these stories in their broader

historical context and over fifty photographs and

illustrations offer a complimentary visual component to the

text.

José C.

Moya

Barnard College

Department of History

Director, Forum on Migration

Authors'

Reply

I would

like to thank Professor Moya for his thoughtful reading of

my book and for a generous review. When I started working

with the documents of an obscure group of rural settlers in

Argentina, I did not imagine that a leading historian of

migrations in Latin America would be interested in drawing

connections between the cases included in my book and those

of other migrations. There is little with which I disagree

in this review, and I will therefore deliberate further on

some of José's thoughts.

On the

issue of hyperbole, I would like to quote Five Years in

Buenos Ayres 1820-1825 (generally attributed to George

Thomas Love, the editor of the British Packet

newspaper): 'en la ropa del gaucho

- salvo el cuero - todo viene de Inglaterra. Los vestidos de

las chinas salen de los telares de

Manchester. La olla de la comida, las espuelas, los

cuchillos.'

Indeed

this book was published in London in 1825, so the author

refers to that specific period after independence, when

pioneering Irish (and Scottish) sheep farmers were exploring

the southern districts of Buenos Aires province. Perhaps the

metonymy can be extended to the second phase, when the Irish

moved their flocks to the western and northern partidos,

probably up to the fall of Juan Manuel de Rosas in 1852. At

that time, the dominant presence of English-manufactured

products in Argentine every-day life, particularly in the

cities, is unquestionable. Even if overstated, my assertion

points to the remarkable Anglophile society that received

the Irish, especially in the early stages of migration.

The other point is about mortality. I based my estimation on

the number of settlers provided by the thesis (1994) and

articles of Patrick McKenna, who elaborates on Sabato and

Korol's study of 1981. Not only was mortality unusually high

during the 1860s and 1870s due to outbreaks of epidemics -

the letters to John J. Pettit provide tragic examples of the

cholera epidemic of 1868 - but it is also important to note

that numbers of male Irish settlers remained unmarried.

Therefore, the size of the Irish community decreased

significantly owing to return migration, mortality and lack

of offspring.

I would

also like to add here that some of my thinking changed after

the first edition of this book in Spanish was published by

Eudeba. This was not totally unrelated to the human nature

of devenir, but it was also part of my own learning

process in the study of emigrants' identities. Some rather

personal aspects changed radically. For instance, nowadays I

do not seek an Irish passport as I once did, in a somewhat

Romantic fashion, a few years ago. I must acknowledge the

significant influence of the referendum of 11 June 2004,

when an overwhelming majority of the Irish voters denied

jus soli to children born in Ireland of foreign parents.

In contrast, I am currently trying to obtain Colombian

nationality (if the consulates in Bern and Buenos Aires

agree on a less bureaucratic method)! My interest in the

larger, and richer, aspects of the Irish in Latin America

was prompted by a myriad of stories that I found in rare

books or other sources, and that are leading my present

writing.

I wish

to thank Prof. Moya for what is, in overall

terms, a very generous review. To him I am truly indebted.

Edmundo Murray