| Wexford

Links with Argentina |

|

Home |

From

Kilrane to the Irish Pampas

The Story of John James Murphy

by Edmundo Murray |

|

Partially

published by The Southern Cross, 127 N° 5860

(Buenos Aires, January 2002)

|

|

| In

a typical summer siesta break in Murphy, virtually everybody

goes home and takes a breather from the heat and from

their rural affairs. But once a year, this peaceful town

with a 4,000 population (1989) is invaded by a crowd of

over 14,000 fans who gather for the Amateur Theatre Festival

(6). With this exception, the region remains quiet

and pastoral, and its people unaware of the intense history

behind the name of their place.

Murphy belongs to the Argentinean Santa

Fe province, 150 km from Rosario and 18 km from Venado

Tuerto. It is located at 33°37’60S and 61°52’W, and

just 99  meters over the sea level. It bears the name

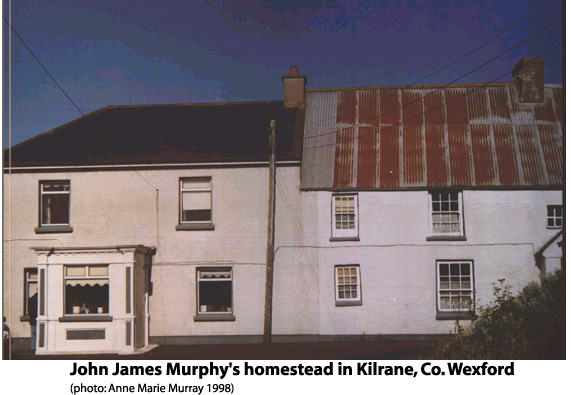

of John James Murphy, born in 1822 in Haysland,

Kilrane parish, Co. Wexford, son of Nicholas Murphy

and Katherine Sinnott (1). When he was 22, 'a very tall, slim and good-looking

youngster' (10), together with his cousins John and Lawrence

Murphy, and friends John O'Connor, Nicholas Kavanagh,

Thomas Saunders, James Pender, Patrick Howlin and others,

he emigrated to Argentina. Before leaving, John 'promised

his mother that when he had £100 he would go back to

see her' (10). meters over the sea level. It bears the name

of John James Murphy, born in 1822 in Haysland,

Kilrane parish, Co. Wexford, son of Nicholas Murphy

and Katherine Sinnott (1). When he was 22, 'a very tall, slim and good-looking

youngster' (10), together with his cousins John and Lawrence

Murphy, and friends John O'Connor, Nicholas Kavanagh,

Thomas Saunders, James Pender, Patrick Howlin and others,

he emigrated to Argentina. Before leaving, John 'promised

his mother that when he had £100 he would go back to

see her' (10).

On 13 April 1844, they left home in

Kilrane, using a cart to reach Wexford town (19 km).

Leaving from Wexford Quay, they sailed directly to Liverpool,

where they invested a small fortune of about £16 each

one to buy their tickets to South America in the brig

William Peile (£16 could be more than their entire

annual income). On 21 April 1844, with 115 Irish emigrants

on board and with the aid of Buenos Aires merchant John

James Pettit, the William Peile weighed anchor

at Liverpool under captain Sprott's command. She called

on 13 May at Saint Jago (Cape Vert islands), and she

was 'becalmed in mid ocean for three weeks' (10). After that, she probably called on Pernambuco, Bahia,

and Rio de Janeiro, and she finally sailed into the

mouth of the River Plate on Tuesday, 25 June 1844. These

splendid lads and their gallant journey inspired a teacher,

Walter MacCormack, to write his epic, characteristically

chauvinist poem 'The Kilrane Boys.' But the situation in the River Plate

was not bright. Rosas was leading his second government,

Montevideo was under Oribe's siege, and the French and

British armies blockaded Buenos Aires.

Murphy

landed with £1 in his pocket. According to his daughter,

when he left Ireland, 'it was principally due to the

treatment the Catholics were subjected to by the English

soldiers, all had to swear allegiance to the Throne

of England giving up their religion or they were ousted

out, no farms or business of any kind could prosper

under such a regime' (10). Once in Argentina, John took advantage of his British

citizenship and his Irish origin, which connected him

to the British merchants and the Irish Catholic priests

in Buenos Aires, respectively. In this way, like most

of his fellow countrymen, he stayed a short time in

the city and he immediately went to the 'camp' (8). With a friend, he 'went to work near Chascomús

with a very well known Argentine family, who never paid

them a cent for their work digging ditches; in those

days there were no fences, sheep were kept apart from

neighboring ones with these deep trenches. That was

his first work in the Argentine' (10).

For eleven years, he also worked hard in Chacabuco as

a sharecropper and tenant in the profitable sheep business.

By 1855, he was already an 'estanciero' in Rojas and

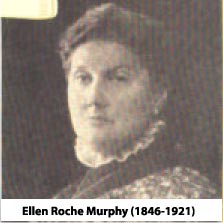

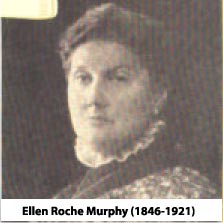

Salto. On 27 May 1867, John got married to Ellen

Roche. Three years earlier, Ellen’s sister Elizabeth

Roche, married to John’s brother William Murphy. And

a third sister, Maggie Roche, married to other pioneer

of Southern Santa Fe, James De Renzi Brett, who would

later buy land for him (1). 'My parents had intended to be married in the

Merced Church. In those days, all the Irish were married

there, always of course by one of their Irish Priests,

but as cholera broke out in Buenos Aires, they were

married in Salto in May, 1867, by Father John Largo

Leahy. My father very wisely thought no one should come

near the city' (10). During Rosas times and afterwards, the men in the

army and the police 'were such savage bruts, the English

Minister of whom Rosas was terrified, ordered all British

residents to fly the English flag over their estancias,

which my father did. He always told us never to forget

he and my mother owed their lives to the English flag'

(10). By 1855, he was already an 'estanciero' in Rojas and

Salto. On 27 May 1867, John got married to Ellen

Roche. Three years earlier, Ellen’s sister Elizabeth

Roche, married to John’s brother William Murphy. And

a third sister, Maggie Roche, married to other pioneer

of Southern Santa Fe, James De Renzi Brett, who would

later buy land for him (1). 'My parents had intended to be married in the

Merced Church. In those days, all the Irish were married

there, always of course by one of their Irish Priests,

but as cholera broke out in Buenos Aires, they were

married in Salto in May, 1867, by Father John Largo

Leahy. My father very wisely thought no one should come

near the city' (10). During Rosas times and afterwards, the men in the

army and the police 'were such savage bruts, the English

Minister of whom Rosas was terrified, ordered all British

residents to fly the English flag over their estancias,

which my father did. He always told us never to forget

he and my mother owed their lives to the English flag'

(10).

In

1869, John Murphy was the owner of two estancias: ‘La

Flor del Uncalito’ in Salto and ‘La Caldera’ in Rojas.

He bought the first one in 1854 from John McKiernan

(topographic survey # 56 of 1855, originally 3/4 leagues,

1,748 hectares). Land in Rojas was purchased in 1864

(survey # 47 of 1864, 4,050 hectares). Later in 1872,

he acquired more land in Rojas (survey # 60 of 1877,

4,050 hectares).

John James (centre) with part of his family

in or before 1895, probably in the house

of Almagro, Buenos Aires city. Left to right:

Isabel, Ellen Murphy (née Roche), J. J.,

Elisa Inés (Cissie), and Jack (or Nicholas).

Photo: Tim Warriner's collection, 2003. |

He

was the first landowner in Northern Buenos Aires to

enclose his holding with wire. When Newton enclosed

his quinta with wire, 'this gave my father the

idea of fencing in all his land. People thought him

mad. After six months they left unpaid, and worked their

way towards Salto' (10). Twenty years later, the ñandubay stakes and bulky

wire he used to prevent sheep loses and to stop the

Indian malón were still noticeable in rural Salto.

'He worked, or slaved rather, day and night and when

he had a little money saved, he rented a small piece

of land on the border of civilization; land there was

cheaper as the indians were practically on top of him.

During those years, he fell ill with small-pox, alone

in a shanty built by himself; an old criolla

neighbour went over every morning to leave him a jug

of fresh water, and empty out what had to be emptied.

This is all the care he had during that awful illness.'

Years later, when he went to Kilrane to visit his mother,

she 'thought he was a stranger when he arrived; it was

only when he spoke she recognised him as her handsome

John, and could only cry and cry. He had been so disfigured

with the small-pox' (10). John worked and worked and deserved his good luck.

He cared for his sheep day and night, 'sleeping little

as he had to go out at any hour when he heard the sheep

bleating, which they were mixing with the neighbouring

ones, and he could not afford to lose even one small

lamb. In 1859, they had a bad year, no rain for months

and months. [...] My father saved his sheep by constantly

throwing buckets and buckets of water over the parched

land and the sheep were able to eat the roots of grass

or weeds they found; they survived on that and water.

He did this day and night and the sheep would rush towards

him as soon as they saw him coming' (10).

'La Flor del Uncalito' in Salto, Buenos Aires.

Compared to the mansions of other estancieros,

mid-19th century Irish sheep-farmer houses

were sober and functional, suggesting

their Protestant work ethic. A 'mirador' was

regularly built on top of the roof to survey

flocks and to anticipate uninvited visits

(i.e., gauchos and Indians). At the turn of

the century, the first generation of

Irish-Argentines was not so sober, and built

expensive houses, frequently on English country

house style, complete with landscape gardens,

tennis lawns, and other amenities. |

'Those

years in the camp were hard for women. It was safer

to have your babies at home, even if you lost some of

them. Doctors did not exist, not one beyond the centre

of Buenos Aires, and most of those with no medical certificate.

When shopping had to be done, John would ride or drive

in to the town of Salto and shop for my mother and their

neighbours, as they all said he had much better taste,

and better memory than their husbands. My mother made

all their clothes, shirts, trousers, everything. If

he spent more money than he had taken with him, he would

say to the criollo shopman, "I will sign for

these things", the criollo would answer "no necesitamos

su firma Don Juan, basta con la palabra del Inglés"

[no need for your signature, Don Juan, enough with a

word of the English]. He was very proud of that' (10).

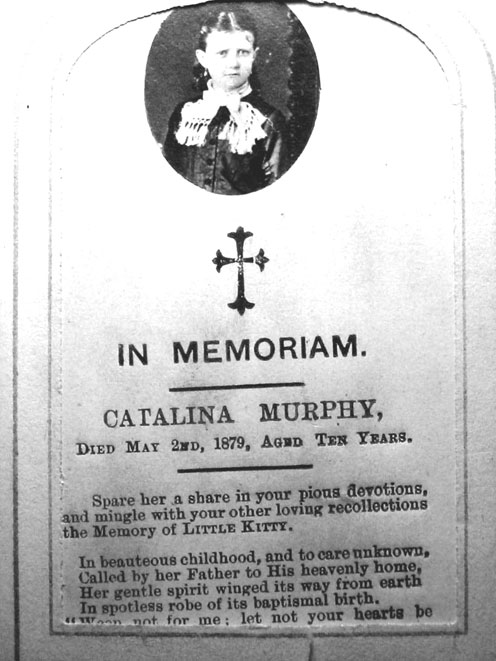

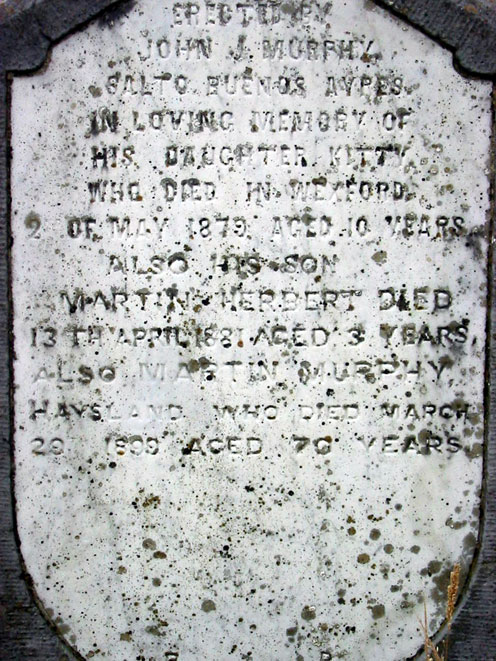

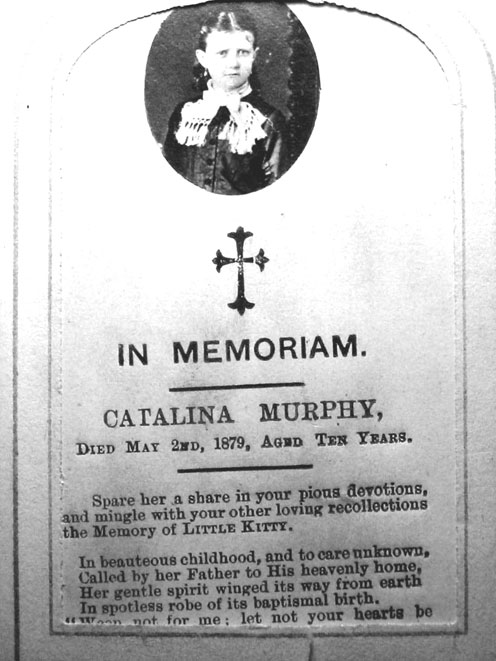

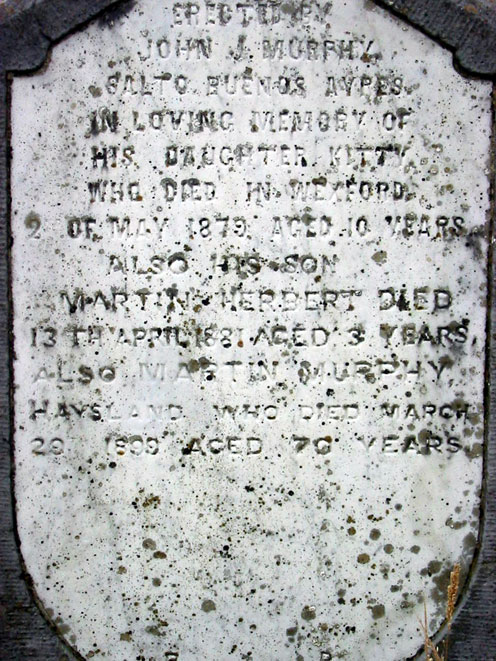

In 1878, John travelled with his family back to Ireland.

Being the elder brother, he had the idea of returning

definitively to Ireland to take care of the family farm.

However, two of his children, Catalina (Kitty) and Martin,

died there, and one son, Nicolás, was born in Mount

Julia, Co. Wexford. Kitty, 'a lovely fair haired

happy child of ten' died of scarlatina. 'In those years,

scarlatina was fatal. No one dared to go near

them for fear of contagion. The other children had been

sent In 1878, John travelled with his family back to Ireland.

Being the elder brother, he had the idea of returning

definitively to Ireland to take care of the family farm.

However, two of his children, Catalina (Kitty) and Martin,

died there, and one son, Nicolás, was born in Mount

Julia, Co. Wexford. Kitty, 'a lovely fair haired

happy child of ten' died of scarlatina. 'In those years,

scarlatina was fatal. No one dared to go near

them for fear of contagion. The other children had been

sent  down to Haysland,

my father's old home, where his sister and invalid brother

lived. She and the children went to see the funeral

passing towards Kilrane churchyard. My mother said it

nearly broke her heart to see the three small ones on

the side of the road watching the funeral pass, not

realising it was their little sister. This was too much

for my parents. My father said "I am leaving and not

coming back: the Argentine has never treated me like

this." He never left the Argentine again.' (10). These sad events, and the relatively poor economic

situation in Ireland, convinced the family to go back

to the River Plate. down to Haysland,

my father's old home, where his sister and invalid brother

lived. She and the children went to see the funeral

passing towards Kilrane churchyard. My mother said it

nearly broke her heart to see the three small ones on

the side of the road watching the funeral pass, not

realising it was their little sister. This was too much

for my parents. My father said "I am leaving and not

coming back: the Argentine has never treated me like

this." He never left the Argentine again.' (10). These sad events, and the relatively poor economic

situation in Ireland, convinced the family to go back

to the River Plate.

They

returned to Argentina on January 1882. Under the favourable

conditions for settlers created after the war against

the Indians, on 15 March 1883, Murphy bought from Eduardo

Casey eight leagues (18,600 hectares, 46,000 acres)

of campo flor in Southern Santa Fe, one of the

best regions of the pampas (4).

With

the help of his family and others, he immediately settled

the area and began wire fencing, building puestos

and planting trees in his new estancia ‘San Juan' (2). He paid off the last of the debt on San Juan the

year before his death. 'His ambition was to die free

of debt [...]. His place in Rojas had been paid off

long before, also the land he bought in Salto from Pacheco

(10).

| By

the end of the century, the prosperous sheep business

was declining, and was replaced by cattle, and later

by grain. Murphy started to let his land to Italian

settlers, who dedicated mostly to corn and wheat.

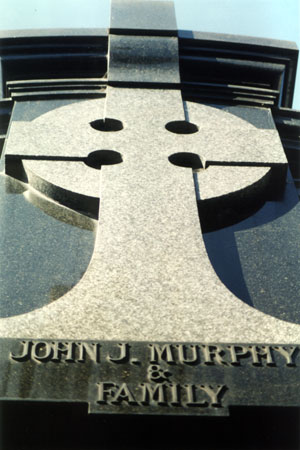

On 13 July 1909, John Murphy died in a house in

Almagro (Rivadavia 4191) at 87 years old, leaving

a large family and quite a serious fortune. 'He

caught cold that developed into bronchitis, bronchopneumonia

followed, and he died in five days without suffering

thank God. He had spent 65 years working and lived

to see his ambition come true, to leave us with

no debts' (10). He was buried in Recoleta cemetery, in the heart

of Buenos Aires city, in an austere monument with

a Celtic Cross. |

|

Most of his land in Santa Fe was sold to 'colonos,'

some of them being ejected by his daughter Elisa Murphy

de Gahan (3), who was living in England, in a way that makes

us think about the evictions of destitute cottiers just

before the 19th century Irish Famine. However, her descendants

argue that 'when she died in 1964, she left her state

to be divided among her eight children or their heirs,

which naturally meant that it had to be sold so that

it could be divided. Unfortunately, it had been mostly

rented out [...] to some French immigrants, and had

been completely neglected - for example, all the windmills

had been allowed to collapse, so that the land could

no longer be farmed - and this meant that it could

only be sold about six years after her death, and at

a very low price. She lived in England only in the years

between the two wars [...]. When he [her husband] died

she returned to Argentina, living mainly in the Alvear

Palace Hotel in Buenos Aires. It is gross misrepresentation

to describe her as responsible for any ejections that

happened years after her death, and were in any case

only what the tenants deserved in the circumstances.

The management of the land and its sales were handled

by the firm of Bullrich' (9). Sources agree on the fact that there were tenant

evictions. Whether they were justified or not, and the

responsibility was of Murphy's descendants or their

administrators, this unfortunate events contributed

to develop the negative perception of the ingleses

(i.e., Irish settlers) and their Pampa Gringa

among some of the newly arrived immigrants in the region. Most of his land in Santa Fe was sold to 'colonos,'

some of them being ejected by his daughter Elisa Murphy

de Gahan (3), who was living in England, in a way that makes

us think about the evictions of destitute cottiers just

before the 19th century Irish Famine. However, her descendants

argue that 'when she died in 1964, she left her state

to be divided among her eight children or their heirs,

which naturally meant that it had to be sold so that

it could be divided. Unfortunately, it had been mostly

rented out [...] to some French immigrants, and had

been completely neglected - for example, all the windmills

had been allowed to collapse, so that the land could

no longer be farmed - and this meant that it could

only be sold about six years after her death, and at

a very low price. She lived in England only in the years

between the two wars [...]. When he [her husband] died

she returned to Argentina, living mainly in the Alvear

Palace Hotel in Buenos Aires. It is gross misrepresentation

to describe her as responsible for any ejections that

happened years after her death, and were in any case

only what the tenants deserved in the circumstances.

The management of the land and its sales were handled

by the firm of Bullrich' (9). Sources agree on the fact that there were tenant

evictions. Whether they were justified or not, and the

responsibility was of Murphy's descendants or their

administrators, this unfortunate events contributed

to develop the negative perception of the ingleses

(i.e., Irish settlers) and their Pampa Gringa

among some of the newly arrived immigrants in the region.

|

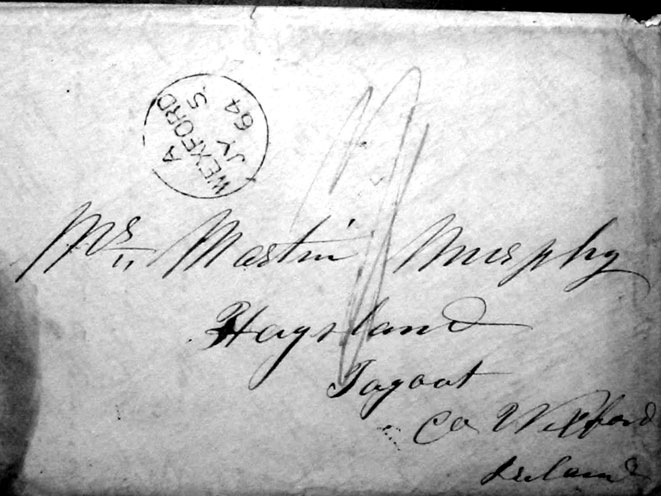

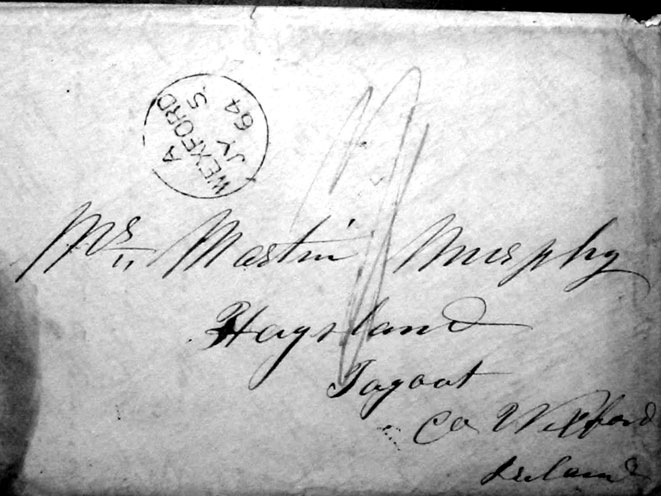

Letter sent by John James Murphy on 27 May

1864 from Buenos Aires, and received

by his brother Martin on 5 July 1864

in Haysland, Co. Wexford.

|

On

22 January 1911, the railway arrived and Estación

Murphy was officially opened in the 86 hectares

compulsory purchased by the Ferrocarril Central

Argentino to John Murphy heirs. The first settler

was the Spanish 'pulpero' Francisco Sisteré.

Others came afterwards to live around the railway

station. In 1931, the name of the town was changed

to Presidente Uriburu, and in 1948, to

Pueblo Chateaubriand, Estación Murphy.

Finally, in 1966, it was officially named just

like that: Murphy, the town of soft siestas

and amateur theatre (2).

|

|

|

|

| Sources |

Top |

| 1)

Coghlan, Eduardo, Los Irlandeses en Argentina: su Actuación

y Descendencia (Buenos Aires, 1987) |

| 2)

Ortigüela, Raúl, Murphy, en Tierras Benditas (Venado

Tuerto, 1991) |

| 3)

Ortigüela, Raúl,,Raíces Celtas (Córdoba, 1998) |

| 4)

Landaburu, Roberto, Irlandeses: Eduardo Casey, Vida

y Obra (Fondo Editor Mutual Venado Tuerto, 1995) |

| 5)

Patrick McKenna, The Formation of the Hiberno-Argentine

Society in: "English Speaking Communities in Latin

America", ed. Oliver Marshall (London: Macmillan, 2000) |

| 6)

Private communications with Agustín Di Mella (Cooperativa

de Electricidad y Servicios Públicos de Murphy) |

| 7)

Website http://www.irlandeses.com.ar/ |

| 8)

Sábato, Hilda, Juan Carlos Korol, Cómo fue la Inmigración

Irlandesa en Argentina (Buenos Aires: Plus Ultra,

1981) |

| 9)

Warriner Gahan, Timothy - private correspondence (30 July

2002) |

| 10)

Murphy, Emily (?), Memoirs of my Father John James

Murphy, Private Collection of the Murphy family -

Mary Anglim (Kilmore, Co. Wexford, August 2002) |

|

Acknowledgements:

many thanks to Mary Anglim, from Kilmore, Co. Wexford, who generously

shared with me her family collection, to Timothy Warriner, London,

for his accurate comments about John J. Murphy's properties, and

to the late Statia Joyce, who during her last days helped me to

identify many characters in old photographs.

| The

Kilrane Boys, by Walter McCormack |

| (ed.

Joseph Ranson, C.C., Songs of the Wexford Coast,

Wexford: John English & Co., 1975, first ed. 1948.),

p. 74. |

|

On

the thirteen day of April in the year of Forty-four

With the bloom of Spring the birds did sing around green

Erin's shore

The feathered train in concert their tuneful notes did

strain,

To resound with acclamations that echoed through Kilrane. |

Twelve

matchless youths I see approach, most splendid they appear.

They leave farewell with all their friends, their neighbours

and parents dear.

As usual to their bosoms flew some mirth for to display;

They cried "Adieu, God be with you; we're bound for Amerikay. |

My

darling boys, what is the cause or the reason you must

go,

To leave your native country for a shore you do not know,

Where you'll profess the holy Faith from which you ne'er

did stray;

Ah, what dull news have you induced to wild Amerikay? |

Foul

British laws are the whole cause of our going far away;

From the fruits of our hard labour they defraud us here

each day.

To see our friends in slavery tied with taxes for to pay.

Ere we'll be bound to such bloodhounds we'll plough the

raging sea. |

There's

Billy Whitty and his bride, their names I will first sound,

John Connors and John Murphy from Ballygeary town.

Mick Kavanagh and Tom Saunders, two youths that none can

blame,

James Pender, Patrick Howlin and four from Ballygillane. |

Larry

Murphy from Kilrane joined them in unity:

They're bound for Buenos Aires, the land of liberty. |

On

Wexford's Quay the thirteenth day were many go bid farewell;

They stayed conversing with their friends till sound of

the last bell.

Then they gave three cheers for Ireland that echoed with

hurray,

And with one for Dan O'Connell they boldly sailed away. |

Oh,

now they're on the ocean, may the angels be their guide

And send them safe through angry wave, o'er rock and welling

tide;

That we may live to meet again in health and wealth and

store.

God send them safely to their friends the blooming Kilrane

corps. |

The

editor Joseph Ranson remembers that he 'got this song from Nick

Corish, St. John's Road, Wexford, Feb., 1943. Nick got the song

from Paddy O'Brien, ex-N.T. (National Teacher), Rosslare. The author

was Walter McCormack of the Bing, Kilrane. A centenary celebration

was held in Kilrane on April 11th, 1944, to honour the memory of

the emigrants, when the cart, which brought some of the emigrants

into Wexford, was drawn in the procession' (p. 75). Mgr. Joseph

Ranson was ordained in 1930 in Salamanca, and was parish priest

of St. Aidan. In 1949, the Irish Archbishop appointed him

to the Directorship of the Irish College in Salamanca. In 1955,

he was Administrator of the Enniscorthy Cathedral. Ranson, a distinguished

historian and literary critic, died on 27 November 1964 (Coghlan

1987: 151).

|

Edmundo

Murray, Irish Argentine Historical Society © 2003 |

Last

Update: 20 April 2004 |

|

|

meters over the sea level. It bears the name

of John James Murphy, born in 1822 in Haysland,

Kilrane parish, Co. Wexford, son of Nicholas Murphy

and Katherine Sinnott (

meters over the sea level. It bears the name

of John James Murphy, born in 1822 in Haysland,

Kilrane parish, Co. Wexford, son of Nicholas Murphy

and Katherine Sinnott (

By 1855, he was already an 'estanciero' in Rojas and

Salto. On 27 May 1867, John got married to Ellen

Roche. Three years earlier, Ellen’s sister Elizabeth

Roche, married to John’s brother William Murphy. And

a third sister, Maggie Roche, married to other pioneer

of Southern Santa Fe, James De Renzi Brett, who would

later buy land for him (

By 1855, he was already an 'estanciero' in Rojas and

Salto. On 27 May 1867, John got married to Ellen

Roche. Three years earlier, Ellen’s sister Elizabeth

Roche, married to John’s brother William Murphy. And

a third sister, Maggie Roche, married to other pioneer

of Southern Santa Fe, James De Renzi Brett, who would

later buy land for him (

In 1878, John travelled with his family back to Ireland.

Being the elder brother, he had the idea of returning

definitively to Ireland to take care of the family farm.

However, two of his children, Catalina (Kitty) and Martin,

died there, and one son, Nicolás, was born in Mount

Julia, Co. Wexford. Kitty, 'a lovely fair haired

happy child of ten' died of scarlatina. 'In those years,

scarlatina was fatal. No one dared to go near

them for fear of contagion. The other children had been

sent

In 1878, John travelled with his family back to Ireland.

Being the elder brother, he had the idea of returning

definitively to Ireland to take care of the family farm.

However, two of his children, Catalina (Kitty) and Martin,

died there, and one son, Nicolás, was born in Mount

Julia, Co. Wexford. Kitty, 'a lovely fair haired

happy child of ten' died of scarlatina. 'In those years,

scarlatina was fatal. No one dared to go near

them for fear of contagion. The other children had been

sent  down to Haysland,

my father's old home, where his sister and invalid brother

lived. She and the children went to see the funeral

passing towards Kilrane churchyard. My mother said it

nearly broke her heart to see the three small ones on

the side of the road watching the funeral pass, not

realising it was their little sister. This was too much

for my parents. My father said "I am leaving and not

coming back: the Argentine has never treated me like

this." He never left the Argentine again.' (

down to Haysland,

my father's old home, where his sister and invalid brother

lived. She and the children went to see the funeral

passing towards Kilrane churchyard. My mother said it

nearly broke her heart to see the three small ones on

the side of the road watching the funeral pass, not

realising it was their little sister. This was too much

for my parents. My father said "I am leaving and not

coming back: the Argentine has never treated me like

this." He never left the Argentine again.' (

Most of his land in Santa Fe was sold to 'colonos,'

some of them being ejected by his daughter Elisa Murphy

de Gahan (

Most of his land in Santa Fe was sold to 'colonos,'

some of them being ejected by his daughter Elisa Murphy

de Gahan (