A

wandering dog, ash trees and Don Martín. He is in his seventies,

and lives in Villa Piaggio, San Martín, one of the most popular

neighbourhoods of great Buenos Aires. Don Martín, a retired

worker from the metallurgic industry, still remembers Maestra

Catalina. When he was about eight years old, his parents

wished to enrol him in the ‘English School of San Martín’,

the school founded by Kathleen Milton Boyle. They wanted to

give him the best possible education, but the tuition was

too high for them, so Ms Boyle waived it. At 76, Don Martín,

originally from Spain, still reads out loud his English copy

of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver's Travels. He is one of

the more or less 3,000 students who were educated by Maestra

Catalina, a pioneer of teaching English in South America. A

wandering dog, ash trees and Don Martín. He is in his seventies,

and lives in Villa Piaggio, San Martín, one of the most popular

neighbourhoods of great Buenos Aires. Don Martín, a retired

worker from the metallurgic industry, still remembers Maestra

Catalina. When he was about eight years old, his parents

wished to enrol him in the ‘English School of San Martín’,

the school founded by Kathleen Milton Boyle. They wanted to

give him the best possible education, but the tuition was

too high for them, so Ms Boyle waived it. At 76, Don Martín,

originally from Spain, still reads out loud his English copy

of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver's Travels. He is one of

the more or less 3,000 students who were educated by Maestra

Catalina, a pioneer of teaching English in South America.

It

is a suburban landscape, with many industries who are today

in poor economic conditions. Lower middle class population.

It is also the place where in the late 1970’s and early 80’s,

shameful events occurred during the Dirty War. One of the

clandestine prisons used by the military forces was located

in the nearby neighbourhood. Torture and slaughtering are

still on the memory of the people. Most of the neighbours

wish to forget the ominous presence of the soldiers and the

absence of their victims. However, they are willing to remember

Maestra Catalina. It

is a suburban landscape, with many industries who are today

in poor economic conditions. Lower middle class population.

It is also the place where in the late 1970’s and early 80’s,

shameful events occurred during the Dirty War. One of the

clandestine prisons used by the military forces was located

in the nearby neighbourhood. Torture and slaughtering are

still on the memory of the people. Most of the neighbours

wish to forget the ominous presence of the soldiers and the

absence of their victims. However, they are willing to remember

Maestra Catalina.

We read

in a 1931 letter to the editor of a Socialist newspaper: ‘I

am a member of a poor workers’ family, and I worked since

I was twelve years old. I am indebted to the generous heart

of my dear teacher Missis Boyle, who helped me to learn

some English. This high-minded and honest lady, whom I admire

and respect, even got me my first job’ (Trabajo, 2

October 1931, letter from Manuel Ramírez). 'Thanks to her

personal recommendations', according to other newspaper, 'many

of her students managed to get very good jobs in the British

companies', many of which had offices in Buenos Aires (El

Noticioso, San Martín, 25 October 1962). Now Catalina

is remembered by a street in Villa Piaggio and a bronze bust

in the entrance of San Martín cemetery.

On

18 October 1869, Kathleen Milton Jones was born in a house

of N° 54 Rathgar Road, Dublin. She was a member of a Church

of Ireland family, who later sent her to England to study

literature in the University of Cambridge. Her mother was

Elizabeth Dowling, and her grandfather, James Dowling, was

a Surveyor in his Majesty’s Customs. Kathleen's father, Francis

P. Jones, was a Civil Engineer. He was employed in the Government

Office of the General Valuation, and died in 1886. Three years

later, when she was twenty, her family emigrated to Rio de

Janeiro following the late nineteenth-century stream of emigration

from Ireland to almost every part of the world. In Rio, she

taught English, Music and Arts in the ‘Colegio Americano Brasileiro’,

but a yellow fever outbreak forced the family to travel southwards.

Two cousins, John and Robert Hallahan, sons of the Rev. John

Hallahan from Castletown, Berehaven (Co. Cork), were working

as medical doctors in the British Hospital at Buenos Aires.

They received Kathleen’s mother and her four children in Buenos

Aires. On

18 October 1869, Kathleen Milton Jones was born in a house

of N° 54 Rathgar Road, Dublin. She was a member of a Church

of Ireland family, who later sent her to England to study

literature in the University of Cambridge. Her mother was

Elizabeth Dowling, and her grandfather, James Dowling, was

a Surveyor in his Majesty’s Customs. Kathleen's father, Francis

P. Jones, was a Civil Engineer. He was employed in the Government

Office of the General Valuation, and died in 1886. Three years

later, when she was twenty, her family emigrated to Rio de

Janeiro following the late nineteenth-century stream of emigration

from Ireland to almost every part of the world. In Rio, she

taught English, Music and Arts in the ‘Colegio Americano Brasileiro’,

but a yellow fever outbreak forced the family to travel southwards.

Two cousins, John and Robert Hallahan, sons of the Rev. John

Hallahan from Castletown, Berehaven (Co. Cork), were working

as medical doctors in the British Hospital at Buenos Aires.

They received Kathleen’s mother and her four children in Buenos

Aires.

Once

in the River Plate, where they arrived in 1891, Kathleen resumed

her teaching profession. In 1894, the Colegio Inglés

(later renamed San Patricio), was founded in San Martín,

open to students of any origin. Once

in the River Plate, where they arrived in 1891, Kathleen resumed

her teaching profession. In 1894, the Colegio Inglés

(later renamed San Patricio), was founded in San Martín,

open to students of any origin.

Five

years later, Kathleen married Andrew T. S. Boyle, a former

Major in the British Army and an engineer, who founded the

San Martín Boy Scouts group. Maj. Boyle was born in 1844 on

a war ship near the shores of north-west India. He went to

the school in England and then entered the Royal Military

School at Sand Hutton. In 1888, serving under the celebrated

Connaught Rangers 88th Regiment – The Devil's

Own – he was promoted to Major. During his appointment

in India, he received eight proud wounds, which he would carry

during the rest of his life. Andrew Boyle, who was also Church

of Ireland religion, became Catholic after a cholera break

in India. As a family member recalls, ‘all the ministers left

with their families and the Catholic priests remained. That

made him change.’ He retired from the Army and was engaged

by a British company with businesses in Argentina. Andrew

Boyle worked in several Argentine cities and his last executive

position was in the Ferrocarril Buenos Aires al Pacífico.

Kathleen and Andrew married in the Anglican

Church in Buenos Aires. She later converted to the Roman Catholic

church and they both remarried and re-baptised their children

in the new faith.

From the time of its opening, the Colegio

Inglés was a laboratory to test modern educational techniques.

Kathleen managed to implement new methods to teach English

as a foreign language and, according to the examination results,

there was a significant improvement of the students’ knowledge

and enthusiasm. Her motivation schemes, including awards to

the best students, prompted the children to work harder. When

the number of students grew and she was not able to teach

to everybody, she hired qualified teachers with diplomas from

prestigious Argentine schools. A newspaper of the 1930’s argues

that ‘the awards should be given to Mrs. Boyle, whose commitment,

effort and determination have been proven during long years

of full-time dedication to her worthy service.’

However,

Kathleen works were not limited to education. Many Sundays,

the Major of San Martín received her request to visit the

prisoners in order to take them cigarettes and magazines.

The three Boyle girls, Catalina, Agatha and Ruth, wandered

several times with her mother through the poor streets distributing

supplies to destitute families. One day, when Kathleen learnt

that a Chinese person had died from an infectious disease

and in appalling circumstances, she was the only one with

the courage to get into his room, wash the corpse, and prepare

it for the burial. These examples chosen among those cited

by newspapers in her obituary are an expression of her qualities.

I wonder if these simple and concrete actions are not a little

outdated today. Does it look unfashionable to spend our Sunday

time on aiding hungry kids or poor immigrants? Nevertheless,

solidarity is a primary duty for individuals like you and

me, and like Kathleen. However,

Kathleen works were not limited to education. Many Sundays,

the Major of San Martín received her request to visit the

prisoners in order to take them cigarettes and magazines.

The three Boyle girls, Catalina, Agatha and Ruth, wandered

several times with her mother through the poor streets distributing

supplies to destitute families. One day, when Kathleen learnt

that a Chinese person had died from an infectious disease

and in appalling circumstances, she was the only one with

the courage to get into his room, wash the corpse, and prepare

it for the burial. These examples chosen among those cited

by newspapers in her obituary are an expression of her qualities.

I wonder if these simple and concrete actions are not a little

outdated today. Does it look unfashionable to spend our Sunday

time on aiding hungry kids or poor immigrants? Nevertheless,

solidarity is a primary duty for individuals like you and

me, and like Kathleen.

As a citizen, the works of Catalina

were exemplar. As a woman, her role in her developing society

was precursory. At that time, Argentina was a country whose

the society was growing dramatically. Its post-colonial bourgeois

structure was changing to an ethnic melting pot of immigrants

from disparate cultures in Europe and the Middle East. On

4 August 1932, an unknown reader sent a letter to the Editor

of The Standard, the newspaper founded in 1861 by the Irish

estanciero Edward Thomas Mulhall and targeted at the

English-speaking community. Signed by Miss Justice,

the letter argued against the quite chauvinistic perspective

that in order to relieve unemployment, working women should

give up their jobs in favour of men. In her letter, Miss

Justice managed to re-focus a gender issue on its actual

social context: a proposed 10% cut on salaries should be applied

only to those with higher income, not to low-paid workers

with large families. ‘Why have they any business to have large

families? I have heard this question discussed by men with

large salaries and only one or two children at most. Who is

more to blame, the rich man with his only son or the poor

man with his 8 or 9 children?’ She ended her appeal to ‘big

salaried men: sacrifice half of your salaries or more if necessary

and see that those working under you earn a living wage, and that their miserable little pittance is no further

encroached upon’ (The Standard, 4 August 1932). The mystery

writer, Miss Justice, was indeed Kathleen Boyle. Shouldn’t

contemporary executives and professionals accept her appeal

to generosity and solidarity?

wage, and that their miserable little pittance is no further

encroached upon’ (The Standard, 4 August 1932). The mystery

writer, Miss Justice, was indeed Kathleen Boyle. Shouldn’t

contemporary executives and professionals accept her appeal

to generosity and solidarity?

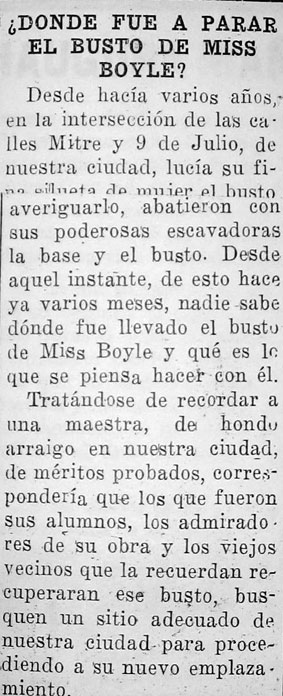

Catalina's

bronze bust in San Martín has a peripatetic history itself.

To honour her memory, a memorial committee submitted a proposal

to the City Hall to place Catalina’s sculpture - a

work of the artist Francis de la Perutta - in a grass island

in 9 de Julio at Mitre, in the heart of the city. On 20 April

1944, the bust was unveiled before a crowd, and many of Catalina’s

acts of charity and her 48 years dedicated to the education

were recalled. However, in 1952 the image of the Irish English

teacher vanished: the grass island was torn up to build a

new approach road to the suburb. The workers placed it on

a municipal storehouse under the bandstand in San Martín’s

main square. Catalina's former students rallied again

and obtained a new location for the bust. In 1956, it was

placed at the San Martín cemetery… though people thought it

was Evita and would either shower flowers or throw rocks at

it! Catalina's

bronze bust in San Martín has a peripatetic history itself.

To honour her memory, a memorial committee submitted a proposal

to the City Hall to place Catalina’s sculpture - a

work of the artist Francis de la Perutta - in a grass island

in 9 de Julio at Mitre, in the heart of the city. On 20 April

1944, the bust was unveiled before a crowd, and many of Catalina’s

acts of charity and her 48 years dedicated to the education

were recalled. However, in 1952 the image of the Irish English

teacher vanished: the grass island was torn up to build a

new approach road to the suburb. The workers placed it on

a municipal storehouse under the bandstand in San Martín’s

main square. Catalina's former students rallied again

and obtained a new location for the bust. In 1956, it was

placed at the San Martín cemetery… though people thought it

was Evita and would either shower flowers or throw rocks at

it!

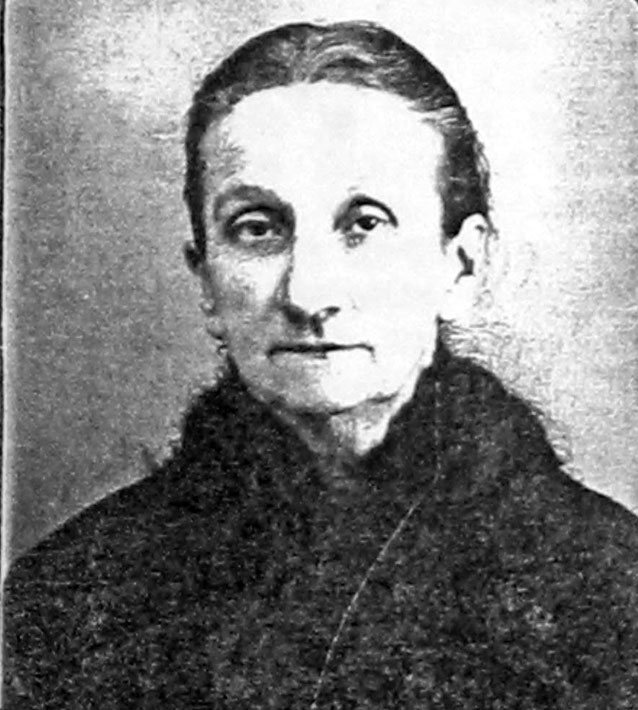

Catalina

remains an example to all of us. Being originally Church of

Ireland and coming from an urban middle-class family from

Dublin, she was not the typical Irish girl who emigrated to

Argentina. The street in Villa Piaggio and the bronze portrait

of a rather stern-looking woman are, as a Buenos Aires Herald

reporter wrote in 1961, the remainders of 'who was, perhaps,

the kindliest woman the city of San Martín has ever commemorated.'

She died

at 72, on 27 October 1941.

|