|

Early Irish

physicians were of the priestly or Druidic caste, their

traditions being handed down orally from remote

antiquity. In many Irish and Welsh tales, Druids appear

as healers. The Druid physicians, called liaig

(2) or, if they were women,

banliaig, were greatly skilled in surgery,

trephination (opening the skull to reduce pressure or

remove brain lesions) and amputations. They also healed

through herbs, healing stones, medicated baths, sweat

houses and thousands of secret verbal charms passed

orally down through the ages. Centuries before the

traditional stethoscope was invented, they used a horn

for assessing the heart beat. Every Irish chieftain was

accompanied into battle by his personal liaig,

and not a few owed their lives - following near-fatal

spear or sword injuries - to the skills of their Druid

physicians (Berresford Ellis 1995: 213-214).

In 487

BC, King Nuadr, the leader of the Tuatha de Danaan, lost his hand at the

First Battle of Moytura (Mag Tuired) against the Firbolgs. He

was given a silver replacement made by the silversmith Credne

Ceard under the direction of Dian Cécht, who was believed to be

the Irish god of healing (Fleetwood 1983: 2).

(3) Dian Cécht’s daughter, Airmid,

was equally renowned for her prowess as a physician and is

credited with identifying over three hundred healing herbs. His

son, Miach, was reputed to be a better physician than his

father, so much so that Dian Cécht slew his son in a fit of

jealousy (Berresford Ellis 1995: 213).

In pre-Christian

times little provision was made for the treatment of those who

were sick and poor. Even in ancient Greece, the seat of

democracy, there was no system of medicine and healthcare that

was available to all, regardless of their position in society.

In most European societies at the time the wealthy and powerful

had their own physicians while the sick poor and elderly were

often put to death as the ultimate solution to their ills.

The first

hospital in Europe was founded by the Roman matron Saint Fabiola who died in 399 AD, near

Rome as a hospice for the sick poor (Berresford Ellis 1995:

214). However, according to legend, the first hospital in

Ireland was founded six centuries earlier, when Queen Macha Mong

Ruadh (who died 377 BC) established a hospital called Broin

Bherg (the House of Sorrow) at Emain Macha (Navan).

Certainly, by the Christian period there were hospitals all over

Ireland, many of which were leper houses, often in the

monasteries that sprang up all over the island (Berresford Ellis

1995: 214-215).

Under the Brehon

laws, the code of great antiquity now recognised as the most

advanced system of jurisprudence in the ancient world, medicine

began to be formalised into a sophisticated system. There were

free hospitals for the sick poor, maintained free of taxation,

with compensation for those whose conditions worsened through

medical negligence or ignorance. Medical treatment and

nourishing food was made available for everyone who needed it,

and the dependents of the sick or injured were maintained by

society until he or she recovered. Each physician was required

by law to maintain and train four medical students and

unqualified physicians were prohibited from practicing. It was

also seen to be important that physicians had time to study or

travel so that they might acquaint themselves with new

techniques and knowledge, and that the clans to which they were

attached made provisions for this. Under the Brehon laws, women

were also eligible to be physicians (Bryant 1923).

The period from

the fifth century until the coming of the Normans in the twelfth

century was, in effect, the Golden Age of ancient Gaelic

medicine, as noble Irish families surrounded themselves with

entourages of learned men, including physicians. Every Irish

lord had his own physician. Physicians, like poets, historians

and musicians, had a high status in Gaelic Ireland, the highest

position being ollamh leighis, or official physician to a

king, chieftain or Irish lord. They were awarded hereditary

tenure of lands for the medical services they rendered. Medicine

was the preserve of a select number of families, father passing

his medical knowledge to son and sometimes to daughter or

kinsman, forming renowned families of hereditary physicians (Nic

Dhonnchada 2000: 217-220).

|

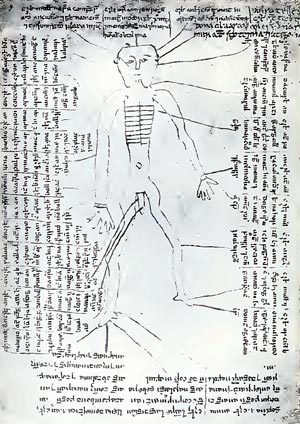

Phlebotomical Chart from an Irish manuscript,

A.D. 1563

(Medicine

in antient Erin,

London: Burroughs Wellcome, 1909)

Special Collections,

Mercer Library,

Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland |

Among the famed

medical families were the Ó Caisides (Cassidys) and Ó Siadhails

(Shiels) of Ulster, Ó hÍceadhas (Hickeys) and the Ó Lees of

Connaught, and the Ó Callanains (Callanans) of

Munster, to name just a few.

Their medical schools, such as that of Tuaim Brecain (Tomregain

in County Cavan) founded in the sixth

century, Aghmacart (in County

Laois), and the medical schools

at Clonmacnoise, Cashel, Portumna, Clonard and Armagh were famed throughout

Europe. (4) Famed

hereditary physicians in Scotland, like the MacBeathas, or

Beatons, who provided medical services to generations of

Scottish kings, originated in Ireland, and Scottish students

studied at the medical school at Aghmacart (Mitchell: 2008).

One of main

functions of the ancient Irish medical schools was the writing

and translation of medical texts into Irish, such as Galen’s

commentary on the Aphorisms of Hippocrates translated

into Irish in 1403 by the Munster medical scholars, Aonghus Ó

Callanáin and Niocól Ó hÍceadha. (5)

A vast body of medical texts exists, written in Irish or

translated from Latin into Irish. Some were of Arabic origin,

thus making available to Irish physicians a wealth of new

medical knowledge and techniques influential in new schools of

Arabic medicine in Europe. These works, together with the books

of the old medical families written in Irish and handed down to

succeeding generations, such as the Book of the O’Lees,

compiled in 1443; The Lily of Irish Medicine, compiled by

the O’Hickeys, physicians to the O’Briens of Thomond, compiled

in 1352; (6) Book of the O’Shiels,

hereditary physicians to the MacMahons of Oriel, and the many

manuscripts written by the O’Cassidys, physicians to the

chieftains of Fermanagh, constitute the largest collection of

medical manuscript literature, prior to 1800, existing in any

one language (Nic Dhonnchadha 2000: 217-220).

Irish physicians

were famed throughout Europe and had connections to the great

European medical schools of the time, such as those of Louvain,

Paris, Montpelier,

Bologna and Padua, forging links

between Continental Europe and Ireland (Dunlevy 1952: 15). The

ancient Irish medical schools existed from before the tenth

century to the end of the sixteenth, when an Irish medical

education and a continental one were regarded as equal. The

Flight of the Earls in 1607 after the Battle of Kinsale marked

the decline of the old Gaelic tradition. Along with the Brehon

laws and the Irish intelligentsia, the medical schools of the

ancient medical families of Ireland were abolished under English

rule, and many of the Gaelic-speaking Irish physicians were

forced to migrate to Europe where they were held in high regard.

Formal Medical and Surgical Education in Ireland to 1900

From the Middle

Ages, medical practitioners in Europe organised themselves

professionally in a pyramid with physicians at the top and

surgeons and apothecaries nearer the base, with

non-medically-trained healers, vilified as ‘quacks’, on the

periphery (Porter 1998: 11). The sick, especially the sick poor,

were treated in monasteries. Surgery, or ‘surgerie’,

bloodletting and the extraction of teeth was delegated to the

monastery lay servants, the barbitonsores, who attended

to the tonsures, involving as it did the shedding of blood.

Thus, surgeons became part of the medieval guild of

barber-surgeons, whose emblem was the red and white pole still

seen outside barber shops today. Only surgeons belonging to the

guild had a right to practice (Widdess 1989: 3).

Formal medical

education in Ireland dates from 18 October 1446 when the Guild

of St Mary Magdalene, to which the Dublin barber-surgeons

belonged, was established by charter of Henry VI, and was the

first medical corporation in Great Britain and Ireland to

receive a royal charter. (7) The

second charter of the barber-surgeons guild in Ireland was

granted by Elizabeth I in 1577. In 1687 the third charter of the

Dublin barber-surgeons was granted by James II, in which

barbers, surgeons, apothecaries and wig-makers were united. Many

surgeons in Dublin, however, did not wish to associate

themselves with barbers. Finally, in 1704, surgeons who were

independent of the barber-surgeons guild called upon the Irish

parliament to separate surgeons from barbers, and apothecaries

from wig-makers. In 1721 the independent surgeons of Dublin

formed a society of their own. The apothecaries were

incorporated separately as the Guild of St Luke by charter of

George II in 1745 (Widdess 1984: 4-5).

In the

eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, physicians and

surgeons were educated separately, surgeons being considered of

lower medical and social status than physicians who belonged not

to a guild, but to a fraternity. The Fraternity of Physicians

was formed in Dublin in 1654, and later incorporated into the

College of

Physicians of Ireland.

The Dublin

University medical school was established in 1711. However, few

medical degrees were conferred for the first thirty years of its

existence and only medicine, or ‘physick’, was taught, no

provision being made for the study of surgery.

In 1745 the

Dublin

Lying-in Hospital (now called

the Rotunda Hospital) was opened. At the time midwifery was regarded by physicians as a

degrading occupation which was practiced by surgeons who bore

the title ‘surgeon and man-midwife’. The same year, a hospital

was founded for the mentally ill, St. Patrick’s Hospital, by the

will of Jonathan Swift, Dean of the St. Patrick’s Cathedral in

Dublin and author of Gulliver’s Travels, who left his

entire estate for that purpose (Widdess 1984:158).

(8) Among the hospitals to emerge in

Dublin in the nineteenth

century were the Fever Hospital

in 1804, Sir Patrick Dun’s and St. Vincent’s in 1834 and the

Misericordiae founded by Catholic nuns in 1861. Also established

were a number of new maternity and children’s hospitals, small

hospitals for the diseases of the skin, and the Adelaide

Hospital with its Protestant charter (Lyons 2000: 63).

Before 1765

there was no systematic training of surgeons except by

apprenticeship. This was a form of indenture for an agreed

number of years, normally from five to seven, the quality of

which depended on the knowledge of the master, the degree to

which he was willing to impart his knowledge and the degree to

which the apprentice was willing to apply himself. There were no

examinations or curricula of required courses. The apprentice

was not paid during the years of his apprenticeship, but was

required to pay a fee to his master who, in turn, provided him

with lodging, usually in his own house, food and clothing.

Sometimes sons were apprenticed to their own fathers, as was the

renowned Dublin ophthalmologist of the nineteenth century,

Arthur Jacob. (9)

Training in

anatomy and other allied subjects in this period was haphazard

or non-existent. Anaesthetics were unknown. If a patient

survived a surgical procedure, his or her wound was in danger of

becoming infected, and death from septicaemia often resulted.

Surgery was confined to amputations, removing exterior tumours,

extracting teeth and blood-letting. Little invasive surgery,

except the extraction of bullets and kidney stones, was

attempted, since death from septicaemia was almost always

inevitable.

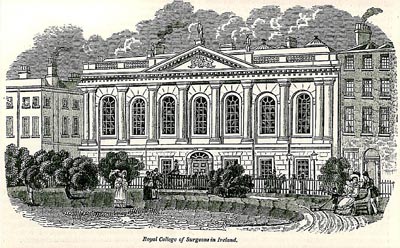

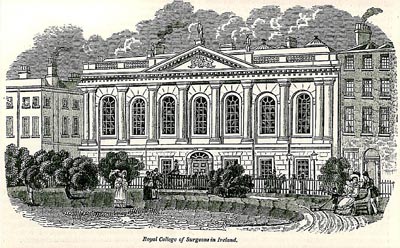

|

Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland circa

1830, by W. H. Bartlett

(Wright, G. N., Ireland Illustrated, London: Fisher,

Son & Jackson, 1833) |

In 1780 the

Dublin Society of Surgeons was formed, having finally broken

away from the barber-surgeons guild to which Catholic Irish had

been refused membership (Widdess 1989: 2). On 11 February 1784,

it received its royal charter, and the Royal College of Surgeons

in Ireland was founded under its first president, Sylvester

O’Halloran. (10)

In its early

years the Royal College of Surgeons granted two kinds of

diplomas: the Letters Testimonial or Licence, and surgeoncies to

the army, of which there were two grades: surgeons and surgeons’

assistants. Later, in 1797, examinations for naval surgeons were

instituted. It can be claimed that one of the chief motives for

the foundation of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland was

to provide surgeons for the British army or navy, a purpose

which was, in fact, expressed in the original Charter (Widdess

1989: 50). Apprenticeship, by which a student was apprenticed to

a member of the College, was a requirement until 1828, after

which it became optional, and ultimately was abolished in 1844 (Widdess

1989: 3).

A licentiate

from the Royal College of Surgeons who wished to further his

medical education had to take a post-graduate diploma in

Medicine by going abroad to Europe or to

Edinburgh or London, for it was not until 1886 that a joint

diploma of the Irish Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons was

established.

From 1804 on, in

the time of the Napoleonic Wars, some seventeen privately-owned

medical schools in Ireland were founded to meet the demand for

medically-trained men. At most of these establishments

facilities for teaching were minimal and in the absence of

conventional dissecting and lecture rooms, stables were used.

Many of the schools existed only for a short time, the need for

surgeons for Wellington’s army diminishing at the end of the

Napoleonic Wars (Widdess 1989: 101).

For all students

of medicine or surgery, knowledge of anatomy was deemed the font

of medical knowledge and this knowledge was acquired through

dissection of human corpses. Following hangings, bodies of

criminals would be carted straight to the dissecting rooms of

medical schools, normally by a back entrance. Despite the high

crime rate in Dublin, there were not sufficient bodies to

satisfy the demand, and a brisk trade in grave-robbing emerged.

The grave-robbers, or ‘resurrection men’, working at night at

burial grounds of the poor and destitute, dragged the

recently-buried corpses from smashed coffins, removed the grave

clothes which they replaced in the empty coffin and put the body

in a sack for delivery to the designated medical school.

(11) Soon the ‘resurrection men’

were supplying the medical schools in London and Edinburgh with

bodies illegally exported in crates as ‘Pianos’ or ‘Books’ (Widdess

1989: 34-38). With the passing of the Anatomy Act in Britain in

1832, permitting the medical profession access to ‘unclaimed

bodies’ - in effect, the poor and destitute without families who

died in workhouses -, grave-robbing came to an end (Porter 1998:

318).

The Académie Royale de Chirurgie, Paris

Medical

education in Ireland was influenced by medical institutions in

France, one of which, the famed Académie Royale de Chirurgie

in Paris, was founded by the son of an Irishman. Georges

Mareschal was born in

Calais in

1658. His father, John Marshall, was an Irish émigré who arrived

in France in the mid-seventeenth century serving as an officer

in a cavalry regiment until his sword arm was amputated

following a serious wound. Orphaned at twelve years of age,

Georges Mareschal was befriended by a local barber-surgeon which

decided his future career. In 1677 he entered the Collège de

St. Cosmé in Paris, the first College of Surgeons in Europe,

which had been in existence since 1255. His skill as a surgeon

was quickly recognised and he became first surgeon to Louis XIV.

Under Louis XV, the Académie Royale de Chirurgie was

founded, becoming the prototype for all future surgical

colleges, including the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland,

with Georges Mareschal as its first President (Widdess 1989:

12-13). One of its future graduates was Michael O’Gorman who

became the one and only protomédico of the Viceroyalty of

the Río de la Plata and the father of modern medicine in

Argentina.

The

Catholic University Medical School

In 1845, under

the administration of Robert Peel during the reign of Queen

Victoria, the Queen’s colleges were founded in Cork, Galway and

Belfast with view to placing higher education on a secular

basis. They were known throughout Ireland as ‘the Godless

colleges’. The Catholic hierarchy viewed such a system as

dangerous to faith and morals and held that Ireland’s future

doctors should have access to a medical education in a Catholic

medical school and not be compelled to enter non-denominational

schools or study abroad. Despite the fact that the founder of

the Royal College of Surgeons, Sylvester O’Hallaran, was

Catholic, as well as eleven of its presidents, by far the

majority of the licentiates, judging by their names, were

Protestant. The only way to obtain a medical degree in Ireland

was from Trinity

College which until 1793 discriminated against Catholics. When

Catholics were admitted in 1845, they were not eligible for

scholarships.

In 1854 the

medical school of the Apothecaries’ Hall in

Dublin was purchased in the name

of Andrew Ellis, a licentiate and fellow of the Royal College of

Surgeons - and a Catholic. Thus, the Catholic

University Medical

School was founded with John Henry Newman, an Englishman and a recent convert

to Catholicism, as rector. Smaller than the medical faculties of

each of the Queen’s Colleges in 1880, by 1900 the

Catholic

University Medical

School outperformed all other Irish medical schools, even

Trinity

College and the Royal College of Surgeons, to become the largest medical school

in Ireland. It was

eventually incorporated into University College Dublin when the

National University was founded in 1909 (Froggatt 1999: 60-90).

The

Golden Age

Dublin was

reputed to be the second city of medical importance in the then

British Empire, second only to Edinburgh. The reign of Victoria

marked the Golden Age of medicine in Ireland. Physicians and

surgeons such as Abraham Colles (1773-1840), Robert Adams

(1791-1875), Arthur Jacob (1790-1874), John Cheyne (1777-1836),

William Stokes (1763-1845), Robert Graves (1796-1853) and Sir

William Wilde (1815-1876) were pioneers in their fields, giving

their names to symptoms and diseases such as Stokes-Adams

syndrome, Graves’ disease, Jacob’s membrane, Colles’ fascia and

Cheyne-Stokes respiration (Lyons 2000: 63-7).

|

The Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland

(Susan Wilkinson, 2000) |

Conclusion

There were, until

the latter years of the twentieth century, Catholic hospitals

and Protestant hospitals where the medical and nursing staffs

were of one religion or the other, just as schools and

universities were separated along religious lines. Happily, that

situation has ended as Ireland has moved towards secularisation

in medicine and education. In recent years Ireland has been

enriched by the mingling of many diverse cultures, philosophies

and religions. Nowhere is this internationalism more strongly

reflected than in its medical schools where more than half the

student body is from abroad, both from developing and developed

countries. These schools have formed links with many countries

of the world in medical training.

Many of the

graduates from the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland and

Trinity

College were surgeons of renown in the armies that fought for South American

Independence. In their own way they contributed to the birth of

the new republics now forming

Latin America. Still more,

throughout the nineteenth century, offered their expertise to

the new republics of Latin America, some preferring to practice

in small towns and communities where doctors were desperately

needed, while others attained renown in cities. Many of the

early boticas, or pharmacies, were established by men

such as the Carlow-born brothers Edmund and William Cranwell,

who had studied at the famed Apothecaries’ Hall in Dublin.

Others, like the nineteenth-century physician Robert S.D. Lyons,

who obtained his medical education at the Catholic

University Medical

School, also in Dublin, risked their

lives in the study of epidemics like yellow fever that

periodically ravaged Iberia, Latin America and the Caribbean. All formed a valued and respected part of the medical community at

large, giving their knowledge gained in

Ireland, Britain

or Continental Europe to the benefit of their adopted countries.

Because of

the Irish doctors and pharmacists who, for various reasons, went

to Latin America and the Caribbean in the eighteenth and

nineteenth centuries, present-day physicians in the region and

the hospitals and academies that Irish physicians helped to

found can rank with their counterparts all over the world.

Susan Wilkinson

Notes

1 Without the help of Mary O’Doherty,

Medical Essayist and Senior Librarian (Special Collections and

Archives), of the Mercer Library at the Royal College of

Surgeons in Ireland, much of the research for this article could

not have been easily obtained, if at all. I wish to thank her

for her help and suggestions in writing this article and for the

insight she gave me into many of the Irish physicians and

surgeons, past and present, whose names are forever linked with

Ireland’s medical schools.

2 The word liaig means

‘leech’, an archaic term for a doctor or healer. The term is

often used for a Druidic doctor in ancient texts.

3 This is the earliest reference to

the fitting of an artificial limb in Western European

literature.

4 For a list of hereditary medical

families and the ancient Irish medical schools, see ‘Medical

Writing in Irish, 1400-1700’ by Aoibheann Nic Dhonnchadha,

Irish Journal of Medical Science, 169 (2000), pp. 217-20.

5 Trinity College Dublin MS 1318,

cols 487.1-499a24.

6 Practica seu Lilium medicinae,

comprising seven volumes of diseases of the body, was written by

the French physician Bernard of Gordon in 1305, and was one of

the best-known medical texts of the Middle Ages.

7 The barber-surgeons of London and

Edinburgh were not incorporated until some years later.

8 This was an entirely enlightened

approach to treating mental illness, as the norm at that time

was to incarcerate the mentally ill in lunatic asylums.

9 The Jacobs were a famous medical

Quaker family in Ireland for four generations. After his

apprenticeship, Dr Arthur Jacob, born in 1790, studied in

Edinburgh,

London and

Paris before returning to Ireland where he eventually taught at

the Royal College of Surgeons.

10 Sylvester O’Halloran

(1728-1807), was a distinguished

Limerick

surgeon and a Catholic, who studied at the Universities of

Leiden and Paris. He was one of the few Irish Catholics to reach

the top of the medical profession in eighteenth-century Ireland.

11 To steal a body was a

misdemeanour, while the theft of garments was a felony,

punishment for which was transportation or hanging.

References

- Berresford

Ellis, Peter. The Druids (Grand Rapids, Minnesota:

Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1995).

- Bryant, Sophie.

Liberty and Law Under Native Irish Rule

(London: Harding & More Ltd., 1923).

- Coakley, Davis

and Mary O’Doherty (eds.). Borderlands: Essays in Literature

and Medicine in honour of J.B. Lyons (Dublin: Royal College

of Surgeons in Ireland, 2000).

- Doran, Beatrice

M. ‘Reflections on Irish medical writing (1600-1900)’ in Davis

Coakley and Mary O’Doherty (eds.) Borderlands: Essays on

Literature and Medicine in honour of J.B. Lyons (Dublin:

Royal College of Surgeons, 2002).

- Dunlevy, M.

‘The Medical Families of Mediaeval Ireland’ in Doolin, William

and Oliver Fitzgerald (eds.) What’s Past is Prologue: A

Retrospect of Irish Medicine (Dublin: Monument Press, 1952).

- Fleetwood, John

F. The History of Medicine in

Ireland

(Dublin: The Skellig Press, 1983).

- Froggatt, Sir

Peter. ‘Competing Philosophies: The ‘reparatory’ Medical Schools

of the Royal Belfast Academical Institution and the Catholic

University of Ireland, 1835-1909’ in Greta Jones and Elizabeth

Malcolm (eds.) Medicine, Disease and the State in

Ireland

1650-1940

(Cork: Cork University Press, 1999).

- Lyons, J. B.

(ed.). 2000 Years of Irish Medicine (Dublin: Eirinn

Healthcare Publications, 2000).

- Lyons, J. B.

Brief Lives of Irish Doctors (Dublin: The Blackwater Press,

1978).

- Medicine in Ancient

Erin

(London: Burroughs Wellcome & Co., 1909). Royal College of

Surgeons in Ireland archives.

- Mitchell, Dr

Ross, Celtic Medicine in Scotland, available online

(http://www.rcpe.ac.uk/library/history/celtic_medicine_medicine_3.php),

accessed

9 September 2008.

- Nic Donnchadha,

Aoibheann. ‘Medical Writing in Irish, 1400-1700’ in Irish

Journal of Medical Science, Vol. 169 (2000).

- Nic Donnchadha,

Aoibheann. ‘Medical Writing in Irish’ in J. B. Lyons (ed.)

2000 Years of Irish Medicine (Dublin: Eirinn Healthcare

Publications, 2000).

- Porter, Roy.

The Greatest Benefit to Mankind (New York: W. W. Norton,

1998).

- Widdess,

J. D. H. The

Royal

College of Surgeons in Ireland and its Medical School, 1784-1984

(Dublin: Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Publications

Department, 1984). 3rd Ed. |