|

Ireland, England and Africa

Thomas

Joseph Hutchinson (1802-1885) was born on 18 January 1802 in

Stonyford, Kilscoran parish of County Wexford.

(2) His father, Alfred Hutchinson,

was a petty landowner from an Anglo-Irish family with a

Protestant background. Although it was reported that Thomas

Hutchinson studied on the European continent and graduated as a

medical doctor from the University of Göttingen in 1833, there

are no surviving records in this institution that could confirm

this. He graduated on 2 January 1836 from the Apothecaries’

Hall, Dublin. By May 1843, Hutchinson was practicing as a

physician and surgeon at Saint Vincent's Hospital in Dublin, a

training ground for doctors and nurses. Six years later he

worked in the Poor Law Union of Wigan, Lancashire (England).

Between 1851

and 1855, Hutchinson was the senior surgeon on board the

Pleiad, for the expedition to the rivers Niger, Tshadda and

Binue, led by John Beecroft. On 29 September 1855, Thomas

Hutchinson was appointed British consul for the Bight of Biafra.

That year he married Mary, his lifelong wife, with whom he

arrived on 29 December 1855 in Port Clarence (later Santa Isabel

and present-day Malabo, capital of Equatorial Guinea), formerly

a Spanish dominion. Most of the business managed by Hutchinson

in Fernando Po was related to British affairs in the region,

which included chiefly the production and transport of palm oil

and occasionally other products. He also represented, albeit

unsuccessfully, a group of freed slaves and their families who

wished to be recognised as British citizens, and was a constant

arbiter between the ship masters and the local producers of raw

materials. (3)

A pioneer of

African cotton production, Hutchinson obtained in 1858 a tonne

of seeds from the Manchester Cotton Supply Associations to

undertake experiments on the continental coast of West Africa.

In his affairs, he was frequently partial to the interests of

certain Liverpool merchants, a practice for which he was

reprimanded by the Foreign Office. Hutchinson remained in Africa

until June 1860, when he and his wife returned to England for

health reasons, together with Fanny Hutchinson, an African girl

they had adopted. On 9 July 1861 he was replaced by Richard

Francis Burton (1821-1890), the celebrated explorer and

translator of The Book of One Thousand Nights and a Night.

(4)

Malaria

During the

journey of the Pleiad, Hutchinson conducted research on

the use of quinine as a preventative measure against the effects

of malaria. He insisted that, in small doses, quinine had a

favourable effect in preventing fever.

The benefits

of quinine were originally discovered by the indigenous peoples

of Peru, who extracted it from the bark of the cinchona tree (quina

quina in Quechua). An effective muscle relaxant, quinine was

used to halt shivering brought on by cold temperatures in the

Andes, and was brought to Europe by the Spanish in the early

seventeenth century. The bark was first dried, ground to a fine

powder and then mixed with wine. It was first used to treat

malaria in Rome in 1631. Large scale use of quinine as a

prophylaxis started around 1850, when it played a significant

role in the European colonisation of Africa. It was the prime

reason Africa ceased to be known as ‘the white man's grave’.

Hutchinson

explained that

My first experience there having been in a

Medical capacity, I made the subject of African malaria and

fever my continuous and attentive study. The truth of the old

maxim that “prevention is better than cure,” with which I

commenced my professional duties at Old Kalabar in the year

1850, which I followed up in the Niger Expedition of 1854, and

which I still practise as well as preach, has been abundantly

confirmed in my experience

(Hutchinson 1858: v).

|

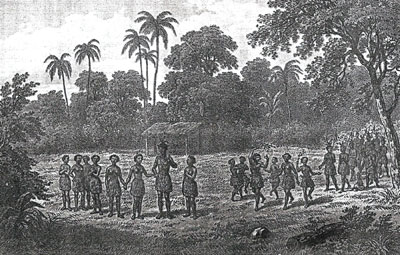

Aboriginal wedding at

Fernando Po

(Hutchinson, Ten Years' Wanderings Among the

Ethiopians, 1861)

|

He ‘was

puzzled to understand how malaria could be generated. […]

Malaria and fever are cause and effect in Africa […] Endemic

fever attacks a large proportion of the crews of nearly every

ship sent out for the purpose of trading’ (Hutchinson 1855:

192). Therefore Hutchinson dedicated his efforts to

understanding how and when quinine should be administrated to

the crew members. ‘As soon as the expedition crosses the bar of

the river, [Niger] they should commence taking quinine, in the

proportion of six to eight grains per diem, one half in the

morning and one half in the evening’ (211).

In this

period, some believed that malaria was caused either by

submarine volcanic action or the action of vegetable matter upon

the sulphates. It was not until 1898 that Ronald Ross in India

proved that malaria was caused by mosquitoes carrying the

protozoan Plasmodium sp. Without knowing the cause of the

sickness, Hutchinson recommended prevention and a hygienic

environment.

Reflecting

Hutchinson’s entrepreneurial spirit, in the late 1850s Bailey &

Wills of Horsley Fields produced ‘Dr. Hutchinson's Quinine

Wine’, marketing it to ship owners and crews.

(5)

Argentina and Uruguay

With friends

and connections in the Foreign Office and various scientific and

business associations, among them George William Frederick, Earl

of Clarendon, and William Bingham Baring, Lord Ashburton, Thomas

Hutchinson managed to balance his consular work and medical

practice with exploration, travel writing and scientific

research. From 1858 to 1867 he was appointed Fellow of some

important institutions, including the Royal Geographical

Society, the Ethnological Society, the Royal Society of

Literature and the Anthropological Society. During his long

life, he was also elected honorary vice-president of the African

Institute of Paris, an honorary member of the Liverpool Literary

and Philosophical Society, foreign member of the Paleontological

Society of Buenos Aires, and founding member of the Society of

Fine Arts in Peru.

|

El Deber (the Paraguayan

Sentinel at his post)

(Hutchinson, The Paraná, with incidents

of the Paraguayan War, 1868)

|

Hutchinson's

next appointment was as consul in Rosario in the Argentine

province of Santa Fe. On 12 July 1861, he arrived with his

family to this city - at that time a small provincial town -

where he also acted as agent for Lloyds. According to Thomas

Murray there were rumours in Buenos Aires 'that Hutchinson got

his appointment and preference from the English Government for

betraying his friends. He was an Irishman and was, it is said,

one of O'Connell's secretaries' (Murray 1919: 310).

Hutchinson’s

ideological platform was quite distinct from Catholic

emancipation and Irish home rule. Therefore it is unlikely that

he had worked as O’Connell’s secretary. Hutchinson's connections

and friends, and his own record of service, were the principal

cause of his appointments in the consular service. This suggests

that the ‘rumours’ were probably the product of Murray’s marked

dislike of anything English.

Between 25

November 1862 and 10 March 1863, with the merchant Esteban Rams

and official support, Thomas Hutchinson organised an exploration

from Rosario to the River Salado in search of wild cotton. As a

result of this journey, he wrote Buenos Ayres and Argentine

Gleanings: with extracts from a diary of the

Salado

exploration in 1862 and 1863,

published in London in 1865.

In 1864 and

until 4 June 1865, Hutchinson was also Acting Consul for

Uruguay. In Montevideo, he owned the Farmacia Británica

at the corner of 25 de Mayo and Ituzaingo. On Hutchinson's

initiative, the governor of Santiago del Estero, Gaspar Taboada,

began testing to produce cotton in his province. In October of

1870 the family left Rosario for England.

Cholera and Native Diseases

Two cholera

epidemics broke out in Rosario in from March to May 1867 and

from December 1867 to February 1868. Cholera was a frequent

visitor during the summer heat and the rainy season. This time

the outbreak was out of control. In April 1867 alone there were

462 victims buried in the church cemetery. Hutchinson was

assisted by his wife and the Sisters of Mercy. They established

a sanatorium in their own house and rendered a great service to

the poor of the city by administering free medicines and

clothing. According to Richard Burton, Thomas and Mary

Hutchinson were scorned in the press by the local doctors. They

used bleeding as the basic treatment and sent dozens to the

grave, but Hutchinson cured his patients by administering

chloroform, chlorodyne, brandy, and turpentine (Burton 1870:

324).

Hutchinson

observed that ‘in some cases, the process just described

occurred in a period of five or six hours from the appearance of

the first signs of symptoms’ of the disease (Hutchinson 1867:

110). He added that the cause was unknown, as ‘it has been since

cholera broke out in 1665 in London or in 1807 in Jessore,

Hindustan, when it extended to Asia and took millions of lives’

(115). (6) He insisted on the use of

quinine as the only prophylactic medicine.

For his

great services during the epidemic, the governor of Santa Fe

province Nicasio Oroño gratefully mentioned Hutchinson in his

message to the provincial parliament. Furthermore, in July 1867

Hutchinson was presented with a gold medal by the Union Masonic

Lodge of Rosario.

During a

journey through the northern part of Argentina, Hutchinson also

studied an intermittent fever, locally known as ‘chuchu’.

(7) ‘Muleteers going from either of

the latter [La Rioja] to one of the former provinces

[Catamarca], and having already suffered from the mild species

of this disease are most predisposed to take it on coming within

its sphere of germination. In such cases it proves fatal to a

large per-centage’ (Hutchinson 1865: 182-183).

His

observations on the South American flora were significant and

completed his medical practice. Yerba mate (Ilex

paraguarensis), a highly-caffeinated tea regularly drunk in

Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, Uruguay, and other countries, has

been the object of frequent commercial enterprises to export it

to Europe. Hutchinson wrote that

there are two qualities of this herb of the

Paraguaya, styled respectively the caa-guazu (large herb) and

caa-mi (small herb). […] When the leaves are fit to be pulled,

they are gathered, toasted, and pulverized. This is done under a

shed, made of posts and covered with the branches of trees. […]

The quantity of yerba exported from Paraguay in a year is

incalculable

(Hutchinson 1865: 142).

|

Ravine on Oroya Railroad

Track

(Hutchinson, Two Years in Peru, 1873)

|

Peru

In 1870

Thomas J. Hutchinson was appointed British consul at Callao, the

port of Lima, where he arrived with his family on the

Cordillera on 22 April 1871. Most of his work in Peru had to

do with shipping, in particular with the problems of crimping by

British and other ship captains. (8)

He also dedicated time to travel and to exploring vestiges and

the burial grounds of the indigenous peoples previous to the

Spanish conquest, an experience he recorded in the two volumes

of Two Years in

Peru, with

Exploration of its Antiquities

(1873).

In his book,

Hutchinson focused on the shipping trade and also on his new

archaeological interests. He regarded the Andean nation as ‘a

mine of archaeological lore, as inexhaustible as her treasures

of silver and gold’ (Hutchinson 1873, I: vii). A good portion of

the first volume includes extracts of his consular reports about

the trade in Callao, with details of agriculture and mining in

Peru. Most of the second volume is dedicated to the archaeology

of ancient cultures in the Andes.

Permeated by

the spirit of illustration and progress, and influenced by the

typical British perception of Latin America in that period,

Hutchinson presented an enthusiastic vision of Peru as a leading

country that

has entered a

new era. […] With these we have the daily-increasing commercial

spirit, chiefly called into life by the Pacific Steam Navigation

Company […]. Peru has a greater length of railways than any

other South American Republic, or even than Brazil. She has

reformed municipalities - made grants for bringing out

schoolmasters from Europe - is putting forth educational and

scientific schemes - proposes outlay for immigration purposes -

and through Congress, as well as the Executive, is presenting to

the world the tout-ensemble of a regenerating progress - needing

only the security of permanent tranquillity to make her hold a

primary position amongst the nations of the world

(I: xiv).

|

(Hutchinson, The

Paraná, 1868)

|

Barbarous Fashions and Civilised Houses

Scarce in medical descriptions,

Hutchinson’s

Two Years in Peru abounds with archaeological descriptions

and commercial reports, as well as in observations and remarks

about the people that are enriched by his medical experiences in

Africa and the Río de la Plata region. ‘The Conibos […] have the

barbarous fashion of flattening the heads of their children with

two small pieces of thin board - one of which is applied to the

forehead, and another behind - in such a manner that the front

of the head is pushed down, and the head enlarged posteriorly,

resembling the skulls that are sometimes turned out of the

burial-grounds (huacas) in the sierras’ (II: 83). Opposite to

this ‘barbarous fashion’ were the works of European residents,

like the

hospital of

Pacasmayo,

in the northern part of the country. Hutchinson visited Dr.

Heath’s ‘excellent institution, like all those built by Mr.

Meiggs, with capacity for accommodating forty to fifty patients’

(II: 167).

The description of houses reflects the same contrast between

the ‘houses at

San José

[…] are most miserable and uncomfortable of residences. […] Not

whitewash, and no arches, no comfortable promenade, excepting

what is built by the foreigners (II: 216).

Retirement and Travel Writing

Hutchinson

resigned from the Consular Service in 1874, though he had been

on leave and off-duty since November 1872. On 21 April 1874 he

was granted a life pension. The family went to live in

Ballinescar Lodge in Curracloe, St. Margaret's parish, County

Wexford, where Hutchinson dedicated himself to writing about his

travel experiences. He travelled through Germany and France, and

in 1876 he published Summer Holidays in Brittany. Then he

moved to Chimoo Cottage Mill Hill near Hendon in the English

county of Middlesex, and finally to northern Italy. Hutchinson

died on 23 March 1885 in his apartment at 2 Via Maragliano,

Florence. He was survived by his wife Mary Hutchinson and their

adopted daughter Fanny Hutchinson.

Edmundo Murray

Notes

1 I am thankful to SILAS Treasurer

Edward Walsh (London)

for his generous hospitality and expert guidance through the

intricacy and formalities of the city's various libraries and

archives. I am also grateful to Roberto Landaburu of Venado

Tuerto for sharing with me interesting information about

Hutchinson, and to genealogist Helen Kelly of Dublin for her

research on the Hutchinson family in Wexford archives.

2 Although

1820 is

mentioned in some sources as the year of birth.

3 The former slaves were liberated

by a British battleship and wished to become British citizens.

They bore English names and spoke pidgin, a mix of

African languages, English and Spanish. They were labelled

Fernandinos by the local population. Some of their names are

visible on the abandoned graves at the old cemetery of

Barrio Ela Nguema,

Malabo.

4 Later in 1865, Captain Burton

followed Hutchinson to South America as the British consul in

Santos,

Brazil. In 1868 he visited Hutchinson

in Rosario.

5 Some other quinine wine brands

were Waters’, Goodall's and Lyman’s. By the end of the

nineteenth century the quinine wines started to be marketed as

tonic waters (eg. Canada Dry, Schweppes). The bitter taste of

anti-malarial quinine tonic led officers and employees of the

British East India Company to mix it with gin, thus creating the

gin and tonic cocktail.

6 In 1866, the British

epidemiologist William Farr identified contaminated drinking

water as the likely source of the disease. However, only in 1883

Robert Koch identified Vibrio cholerae as the bacillus

responsible for the disease.

7 Chucho. Hutchinson’s

writing includes frequent and startling misspellings of common

nouns, toponyms and other proper names in Spanish and French

languages.

8 ‘Crimping’ (‘Shanghaiing’ in

American English), was the practise of conscripting men as

sailors by coercive techniques such as trickery, intimidation,

or violence.

References

- Burton,

Richard F. Letters from the battlefields of

Paraguay

(London: Tinsley, 1870).

- Hutchinson

T. J. ‘El cólera en el Rosario. Informe sobre la epidemia en el

Rosario, durante el mes de abril de 1867’ in Revista

Médico-Quirúrgica (Buenos Aires), 4:7 (8 July 1867), pp.

106-12.

- Hutchinson

T. J. Buenos Ayres and Argentine Gleanings: with extracts

from a diary of the

Salado

exploration in 1862 and 1863

(London: Edward Stanford, 1865).

-

Hutchinson T. J. Impressions of Western Africa, with remarks

on the Diseases of the Climate and a Report on the Peculiarities

of Trade Up the Rivers in the Bight of Biafra (London:

Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans and Roberts, 1858).

-

Hutchinson T. J. Narrative of the Niger, Tshadda, & Binuë

Exploration, including a Report on the Position and Prospects of

Trade up those Rivers, with Remarks on the Malaria and Rivers of

West Africa (London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans,

1855).

- Hutchinson

T. J. Our Meat Supply from Abroad: A paper read before the

Liverpool

Literary and Philosophical Society, January 9th 1871

(Liverpool: David Marples, 1871).

- Hutchinson

T. J. Summer Holidays in

Brittany

(London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Riwigton, 1876).

- Hutchinson

T. J. Ten Years' Wanderings among the Ethiopians; with

sketches of the Manners and Customs of the Civilized and

Uncivilized Tribes, from

Senegal to

Gabon

(London: Hurst and Blackett, 1861).

- Hutchinson

T. J. The Paraná; With Incidents of the Paraguayan War, and

South American Recollections from 1861 to 1868 (London:

Edward Standford, 1868).

- Hutchinson

T. J. Two Years in

Peru, with

Exploration of its Antiquities

(London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low & Searle, 1873). Two volumes.

- Hutchinson

T. J. Up the Rivers and Through Some Territories of the Rio

de la Plata Districts in South America [Read at the 38th

Meeting, 1868, of the British Association for the Advancement of

Science, in Norwich, on the 21st of August, Section

E, Geography and Ethnology] (London: Bates Hendy & Co.,

1868).

|