|

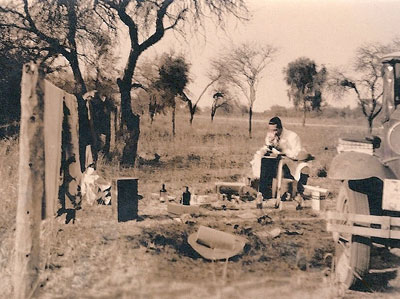

Dr Geoghegan taking

field samples in Catamarca

(Geoghegan family collection)

|

The descendents of Irish people have, in general, maintained a striking level of involvement and participation in community as well as political affairs in Argentina.

Virtually ignored by historians, many have been long forgotten. Arnoldo Jesús Andrés Geoghegan (1898-1978), a man of many talents, is a case in point. He was born in Arrecifes, the grandson of Andrew Geoghegan and Sara Mills, both from Ireland,

who settled in Argentina in 1843. The couple had twelve children. Around the year 1870 they went to live on an

estancia (ranch) in Pergamino which they named ‘Emmett’ in honour of the Irish

patriot, Robert Emmett. The ancestry of the MacGeoghegan clan, as they were originally called, originated from a southern branch of the O’Neills; they even claimed family ties to the legendary Niall of the Nine Hostages of the sixth century. The family home was in the current-day barony of Moycashel, County Westmeath, with the head of the clan’s residence located nearby in the town of Kilbeggan. The family was quite noteworthy in Cromwellian times, suffering severely from the ravages of the wars of that period and the subsequent loss of their wealth (MacLysaght 1957). The family coat of arms bears the motto: ‘always at the ready to serve one’s motherland’ and it can be said that Arnoldo Geoghegan’s life came as a response to that ancestral calling.

Arnoldo studied at the College of San José, Buenos Aires. At the age of twenty-eight he formed part of the first group of Argentine bacteriologists to graduate from the Bacterial Institute of the Department of National Hygiene (present-day Carlos G. Malbrán Institute). Scientific research was the focus of his

life's work, carried out within various public bodies up to 1928, the year he was named Director of the Anti-Malaria Laboratory of the Department of National Hygiene in Catamarca

Province. At first he was only meant to stay for six months, but as he later said to a local newspaper; ‘they wouldn’t let me go’ and it was there in Catamarca where he was to remain for the rest of his days

(El Sol, 5 September 1976). His enthusiasm for the fresh challenges presented in a province in dire need of epidemiological study and research forced him to move his family from the affluent neighbourhood of Belgrano,

in the city of Buenos Aires to the arid reality of Catamarca. In this period he discovered the first cases of

chagas in the province and he had the wisdom to have those suffering from it taken to the National Academy of Medicine in Buenos Aires for treatment. (3)

|

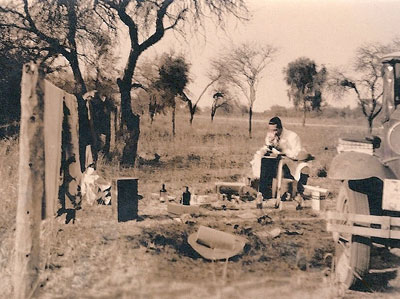

Working against

brucellosis at Tambo Fanor Galindez, August 1937

(Geoghegan family collection)

|

Geoghegan was the sole bacteriologist in the province for a period of over fifteen years. ‘It was an arduous struggle because I was alone. I had nowhere to go for a second opinion nor was there anyone who knew anything about my field’ (El Sol, 5 September 1976). The scope of research that could be done at the time was very limited, due to lack of necessary basic elements and drugs. However he had the energy and professional prowess to overcome these problems, as well as those occasioned by the lack of a national health policy that might support his work. His research was extensive; it covered

brucellosis, chagas disease, typhoid, bubonic plague and malaria amongst other infectious diseases. Further, he actively participated in eradication campaigns and schemes with his camera and ‘mobile laboratory’.

His efforts soon earned him acclaim and it was not long before he was made a member of the National Commission for the

Study of Brucellosis. In addition, he received recognition from the management of the Malbrán Institute and the National Commission for Scientific and Technical Research. Perhaps the most notable accolade he received was from federal senator Alfredo Palacios, who praised Geoghegan as a ‘wise young man’, while at the same time denouncing the fact that although the government paid tribute to him for his work ‘this wise young man is still alone, left without resources in his noble scientific quest, without any government aid, doing the best he can with the scant means at his disposal.’ After detailing all Geoghegan’s achievements and the deficiencies of the government in withholding from him the few materials he had requested during ten long years of solitary research, Palacios concluded by saying that ‘we

legislators see things from the viewpoint of the capital city, not from a national or Argentine perspective. We have thought we could pay our debts to the

Northern provinces by now and then voting to build a ditch or a road or a railway or to regulate an industry.

But when have we cared about the people?’ (Argentine Senate, 28 August 1941). Senator Palacio’s remarks were so accurate that as Geoghegan continued with his research, he was forced to provide for his wife and three daughters by working as a Laboratory Supervisor in the San Juan Bautista Hospital as well as teaching physics and chemistry

at several schools in Catamarca.

Even though research was the main focus of his career, Geoghegan also had other concerns and worries which prompted his involvement in a number of other pursuits not directly associated with his profession. In 1930 he accepted the offer made by Monsignor Ramón Rosa to streamline the Catholic church-owned newspaper

El Porvenir. He completely reorganised operational practices in order to transform it into a daily newspaper. His endeavours to

harmonise various visions within the Church itself prompted him to change the name of the broadsheet to one which was a little more suggestive:

La Unión. Once the dust had settled on the sweeping changes instigated by Geoghegan, in 1931 he left the paper in the hands of a journalist so that he could get back to his beloved research and embark on other new ‘adventures’.

|

Dr Geoghegan (left)

at the malaria laboratory, 1928

(Geoghegan family collection)

|

These included the promotion of tourism in the city of Catamarca as well as his acting as local regional correspondent for the Buenos Aires daily

La Razón. He set up a tourist office at his workplace as well as collaborating intensively with the Eucharistic Congress in Catamarca. The undertaking led to the edition of a tourist guide for the region in 1937. Once retired, he went on editing a monthly magazine entitled

Tierras Norteñas (1958), the administration of which was carried out at

his own residence ‘La Florida’. In 1944 he founded the Catamarca Horse Club, which even participated in several parades in Buenos

Aires. This was in addition to his organising the National Poncho Festival. To support

urban progress he donated lands to the Municipality of Catamarca and to the Provincial Roads Authority, contributing greatly to the urban development of streets and avenues for the area. He also gave the waterworks authority some land to dig a well to supply the zone with water.

As we can expect from such an ambitious and multi-talented man, politics was never

off his personal agenda. According to his daughter Nelly, her Peronist father was an idealist, who from the very beginning supported Juan Domingo Perón and Perón’s close friend Vicente Leónidas Saadi. (4) Together with his employees he even made a contribution to the Eva Perón Foundation. His backing of Perón’s radical government earned him the position of Director of Catamarca Mining Authority and Director of the School of Mining of the province, posts which he held until 1948, when he was named Head of the Central Regional Laboratory of the Argentine Ministry of Public Health. This position, more in keeping with his field of expertise, allowed him to form part of a technical team

that worked alongside the first national Minister of Health, Ramón Carillo. (5) The group’s work included both day-to-day functions as well as the development of long-term strategies of government, such as the Second Five-Year Plan.

It is important to place the situation in context. Infectious and contagious diseases constantly reappeared throughout the second half of the twentieth century, while new pathogens presented themselves to challenge the optimism of modern science. Although many of these illnesses did not affect the public on a huge scale, it is interesting that a number did indeed garner public attention. They had the further effect of making the authorities take political action or create specific institutions for combating them, or alternatively leading to the authorities’ covering them up, since the existence of certain diseases and illnesses had repercussions for the legitimacy of whichever government was in power at the time (Ramacciotti 2006: 115-138).

|

Geoghegan (left)

marching in a gaucho parade at the

First National Poncho Festival, 9 July 1967

(Geoghegan family collection)

|

Although many of the projects developed by Geoghegan had been previously debated by the politicians, they had in reality done little, due both to the small size of the health budget as well as to the many and varied regional obstacles that Geoghegan had to surmount. It is likely that the fear of the possible social and political consequences of a natural event such as an epidemic persisted in the minds of government officials. The San Juan earthquake of 1944, for which Perón oversaw relief and medical aid, had become a milestone in his acquisition of political power (Ramacciotti 2006: 115-138).

Within this framework and in response to Carillo’s expressed appeal, Geoghegan postponed his retirement in order to draw up the Second Five-Year Plan: ‘I am more willing than ever, in as much as I can, to collaborate fully and enthusiastically with the execution of the said Plan, one for which Your Excellency serves as an example of the achievements of the Government’ (Geoghegan to Carrillo, 9 August 1953). The available documentation shows that Geoghegan had more interest in carrying on with his research than with executive duties. On several occasions he asked to be designated a Researcher and to be assigned the economic resources and freedom of action he needed to ‘encourage and carry out research of fundamental interest for Public Health and to be allowed to do so in any part of the province.’ These requests went unheeded.

Although it may be assumed that Geoghegan’s life gave him much satisfaction, some of his letters and requests reveal the anxiety that many Argentine researchers still experience today. In 1958, he presented a plan to contribute to the study and eradication of

brucellosis. He pointed out that since 1931 he had been researching the development and spread of the disease, inspired only by the desire and satisfaction brought by the pursuit of knowledge. He had received no official support whatsoever, and in consequence his research had not attained the importance he felt it merited. He complained that health in the

northeast of Argentina had been ignored, and that no action had yet organised.

Official indifference left a man such as Geoghegan, so full of ideas and concerns, to his own devices. Yet Geoghegan’s wide-ranging and disinterested research single-handedly resulted in important advances in the field of bacteriology in Argentina. Arnoldo Geoghegan left his mark and showed his deep level of commitment to the community where he lived.

Carolina Barry

Notes

1 University of Tres de Febrero (Buenos Aires). An earlier version of this article was published in

The Southern Cross, 133: 5934 (February 2008). I am thankful to the Geoghegan family for their contribution to Arnoldo Geoghegan’s biography.

2 National University of Ireland, Maynooth.

3 Chagas disease (in Spanish: mal de Chagas-Mazza, also called American trypanosomiasis) is a tropical parasitic disease caused by the flagellate protozoan

Trypanosoma cruzi. Brazilian physician Carlos Chagas was the first to describe the disease cycle in 1909, while the Argentine researcher Salvador Mazza studied the complete process in 1926.

4 A number of Irish Argentines played roles in Argentine Peronism. See Barry, Carolina, 'Politically Incorrect: Irish Argentines in the Early Peronist Period' in

Irish Migration Studies in Latin America, 3:6 (November 2005), pp. 69-76.

5 Many historians highlight the achievements of Ramón Carillo during his time in office. Without a shadow of doubt the span of his administration had been unrivalled up to that point in terms of the number of projects carried out.

References

- Argentine Senate,

Diario de sesiones, 28 August 1941.

- Barry, Carolina, 'Politically Incorrect: Irish Argentines in the Early Peronist Period' in

Irish Migration Studies in Latin America, 3:6 (November 2005), pp. 69-76.

-

El Sol (Catamarca), 5 September 1976.

- Geoghegan Family Collection, including letter from Arnoldo Geoghegan to Ramón Carrillo, Minister of Health, 9 August 1953, and ‘El bocio y zonas bocigenas, nicrofotografías, triatomas infectors, disenteria bacilar tipo shiga, enterovirus vermicularis, epizootias, fiebre ondulante, tifus, helmintiasis, etc.’,

in: Investigaciones efectuadas en la provincia de Catamarca por Arnoldo

Geoghegan.

- Karina Ramacciotti, ‘Política y enfermedades en Buenos Aires 1946-1953’ in

Asclepio. Revista de la medicina y de la Ciencia, 58:2 (July 2006), pp.115-138.

- MacLysaght, Edward.

Irish Families: Their Names, Arms and Origins (New York: Crown Publishers, 1957).

|