|

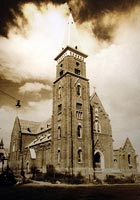

The Fourth of July is a date synonymous with freedom and the Declaration of Independence in the United States, but it also marks the little-known story of one of the most brutal repressions of Argentina’s so-called dirty war from 1976 to 1983, the most bloody dictatorship in the nation’s history. On that day in 1976, six members of the Argentine Navy entered the St. Patrick’s parish house in Belgrano, Buenos Aires, and assassinated five religious: the priests Pedro Eduardo Dufau, Alfredo Leaden and Alfie Kelly and the seminarians Salvador Barbeito and Emilio Barletti. Their bodies were left in place, arranged execution style, while the walls were graffittied

with slogans accusing the priests and seminarians of being

communists and confirming that their deaths were a warning to

those who 'poisoned the minds of the young.'

Young and Zubizarreta’s documentary questions why this group was targeted when the hierarchy of the Catholic Church at the time closely allied itself with the military dictatorship. The answer to this question is provided by contemporary television and newspaper archival footage, which presents a deeply divided Argentine society racked by violence and insecurity. The church was not exempt from these divisions and was essentially torn between conservatism and a deep commitment to social reform inspired by Vatican II and liberation theology. The deaths of the members of St. Patrick’s crystallised this schism, as the murdered men had been accused of being

'zurdos' - left-wing and even communist revolutionaries. The fact that the church seemed to have had little interest in investigating the killings parallels the efforts of the government to cover up its use of the mechanisms of the state to rule by terror.

Young and Zubizarreta spent six years accumulating the archival footage that is used to powerful effect to re-create the climate of fear and paranoia that the early part of the film evokes. Significantly, they were forced to look outside Argentina for a great deal of this material, which they eventually located in CBS studio archives in the United States. This footage is intertwined with equally powerful and often emotional testimonies from other members of the congregation; the journalist and historian Eduardo Kimel, whose book

La masacre de San Patricio (The St. Patrick’s Massacre) inspired much of the film; excerpts from Alfie Kelly’s diary; and interviews with the mothers of the seminarians. Despite the fact that the title refers to the particular events of 1976, the film has a two-part structure, with the first section concentrating on the massacre and the second following the story of Bob Kilmeate, a former Pallotine priest.

The first section of the film deals with the massacre, placing it within a historical context of a politically and socially fragmented society and the ambivalent attitude of the institutional church in Latin America to liberation theology. Kimel’s persuasive and eloquent account of these events does much to provide this part of the film with a clear structure. Interviews with Fr Kevin O’Neill, the mentor of the members of the congregation dedicated to the tenets of Liberation theology, form a moving tribute to the murdered men. The excerpts from Kelly’s diary and the interviews with the mothers of the seminarians vividly communicate the atmosphere of fear and suspicion that pervaded Argentina at the time, as Kelly writes of death threats against him while both mothers dreamt that their sons would be killed. The film also effectively chronicles the church’s collusion with the regime and the paradox that the junta leader Admiral Videla was profoundly religious and even attended the funerals of the men his henchmen had murdered. The only questionable decision in this part of the film is the reenactment of the moment when the assassins enter the parish house through the church, during which one faceless killer blesses himself. Presumably the intention here was to underline the connection between the church and the military, but this has already been persuasively established and the use of this brief scene opens the directors to charges of dramatising rather than reporting the events portrayed.

The second section of the film deals with Kilmeate’s difficulties as a result of his friendship with his former colleagues. He too is suspected of being a communist and possibly a terrorist. After his ordination, only O’Neill supported him, insisting that he stay in the parish though he was sidelined into youth ministry. Kilmeate’s determination to continue to help the poor led him to be transferred to Patagonia, where he was finally forced to leave the order as a result of a smear campaign roundly condemned as slander by O’Neill. His tale has a surprisingly hopeful conclusion, however, as he and other former St. Patrick’s seminarians continue to work to help the disadvantaged by defending the land rights of small farmers in Patagonia and forming collectives to help farmers secure fair prices for their goods. At first, the decision to continue the film to the present day through Kilmeate’s story seems rather puzzling, yet this is perhaps the greatest tribute that the film makes to the murdered men: the work of Kilmeate and others shows that the ideals they upheld have not died and that change is possible, albeit, in this case, outside the church.

Although many fictional and documentary films have dealt with the dirty war, remarkably few have addressed the relationship between the Catholic Church and the dictatorship. Luis Puenzo’s

La historia official (1985), the only Argentine film to win an Oscar, features a brief scene where the protagonist is shocked to learn that her parish priest supports the military’s repression. Another key feature

film made after the return to democracy, Jeanine Meerapfel’s

La amiga (1988), contains a similar sequence. These films and a number of recent documentaries, such as Pablo Milstein and Norberto Ludin’s

Sol de noche (2002) and Albertina Carri’s Los rubios (2003), differ greatly in style and form, but all concentrate on the plight of the disappeared.

4 de julio is therefore a remarkable documenting of the collusion between church and state during the dictatorship that contributes to a greater understanding of the ideological confusion of the regime. In terms of its contribution to filmmaking about the period, it seems to me that the film more than lives up to Aldofo Perez Esquivel’s prescription that contemporary Argentine documentary makers must make it clear, through their presentation of events and testimonies, that the past is part of the present (cited in Campo and Dodaro eds., 2007, p.8). Through their skillful use of documentary evidence, interviews and the continuation of the legacy of liberation theology in the second half of the film, Young and Zubizarreta succeed thoroughly in making the events of the 1970s and 1980s relevant to today’s Argentina. This film also has deep resonances for Irish audiences, as the lively debate following its premiere on April 28 at the National University of Ireland, Maynooth, organised by the Department of Spanish, illustrated. Not only is

4 de julio a singularly moving tribute to the members of St. Patrick’s, but it has much to teach Irish audiences about the history of the Irish clergy in Latin America.

Catherine Leen

(1) Dr Catherine Leen, Lecturer in the Department of Spanish, National University of Ireland, Maynooth

References

Javier Campo and Christian Dodaro, (eds.),

Cine documental, memoria y derechos humanos (Buenos Aires:

Ediciones del movimiento, 2007).

Author's Reply

I would first like to thank and

congratulate Dr Catherine Leen for having achieved a

precise and profound synthesis of the complex story that

the film seeks to narrate. It is interesting to observe

that she takes issue only with the scene in which we

reconstructed the crime in fictional form, and

particularly the moment in which one of the murderers,

before entering the parish to massacre the priests and

seminarians, makes the sign of the cross.

Never before had I questioned myself on

the validity or otherwise of that action. This is

interesting as I can understand that it is an emphasis

that probably is rendered redundant. Both for me and for

the co-director Pablo Zubizarreta, it was essential to

demonstrate that the murderers of the Pallotine priests

were not only Catholics but also had the conviction that

they were doing something good in relation to their

Christian faith in eliminating the impostors and

heretics of St. Patrick’s. This issue is even more

controversial for Argentinean Catholics and it has been

so difficult to talk about this topic that, perhaps

because of this (I am not justifying myself but rather

seeking to understand our decision), we have never

doubted the necessity of including this action.

Once again thank you to Dr Leen for her

fully constructive criticism and to Edmundo Murray for

the possibility that he has given us to disseminate this

story.

Juan Pablo Young

Translated by Claire Healy |