|

Life

changes

Then my

life changed greatly. For a long time I had questioned the

whole concept of celibacy in the priesthood. It all came to a

head for me in 1981 when I decided to opt out of the ministry.

With a heavy heart I left the South Andes and settled in Lima

where I commenced work with a Peruvian NGO called Servicios

Educativos Rurales (Rural Educational Services), an NGO

dedicated to the rural population of Peru, the campesinos,

the very kind of people I had ministered to previously. Now I

would be working with them on a national level, obviously in a

different role. This NGO had various areas of work; I began

work in the Communications Area where we edited a magazine

called 'Andenes' in order to help the campesinos

at a national level to be informed on the political, agrarian,

social/economic and the cultural and ecclesiastical realities

of Peru. I was responsible for a section of the magazine we

called Nuestras Costumbres (Our Customs). In that section over

the years we published the campesinos' own accounts of

their customs, their fiestas, their agrarian rituals,

their poetry, their stories and their legends. We also held

annual competitions to invite them to paint and draw the

reality in which they were living.

|

With Eamon de Valera and Fr. Killian Healy in

the Carmelite Theologate, Rome 1961 |

I remember

1992, the year Spain celebrated what they called the 500th

anniversary of the 'discovery' of South America. I think later

they changed the wording of 'discovery' to 'el encuentro de

dos culturas' (the meeting of two cultures) because of

protests from South America against the use of the term

'discovery'. Not that a 'meeting of two cultures' pleased

South Americans either, for they saw it more as an invasion or

even as a genocide. On that occasion we invited the

campesinos of Peru to paint or draw what they felt about

the arrival of the Spaniards to their country and the

consequences for themselves. I could safely say that it was

the first time that native Peruvians had been asked to express

their opinions on a topic that had such devastating

consequences for them over the centuries. And express it they

did, portraying graphically the many forms in which the

indigenous population have suffered exploitation and

injustices to this very day.

Governments come and go

In the

thirty years that I lived in Peru, I saw several governments

come and go. When I arrived in Peru in 1964, Fernando Belaúnde

Terry was the democratically elected president. Four years

later I was back in Ireland on my first holiday back home when

one morning after breakfast a fellow Carmelite asked me, 'Des,

did you hear, your president had been deported from Peru?' In

the early hours of 3 October 1968, a bloodless military coup

led by General Juan Velasco Alvarado surrounded the

presidential palace. Belaúnde was taken out in his pyjamas and

later that day sent on a plane to Buenos Aires. So began

twelve years of military dictatorship.

The armed

forces have always played a decisive role in Peru's political

history. Since 1930 there have been four periods of military

rule lasting a total of thirty years. For most of this century

the military's political interventions were in support of the

right, but during the Velasco government (1968-1975) a new

current of reformist nationalism became dominant within the

armed forces. The Velasco government implemented a radical

programme which marked the first decisive break with the

economic model imposed by the Spanish conquest. This involved

ending the political domination and economic power of the

oligarchy; the modernisation of the Peruvian state and a major

expansion of its role in the economy; the search for a more

equitable relationship with foreign capital; and major changes

in land and property ownership.

Twelve

years later, Belaúnde made a comeback when a more moderate

General Morales Bermudez moved towards restoring democracy and

allowed new elections, permitting Belaúnde to return again to

popular acclaim. Belaúnde thus commenced his second term as

president in July 1980 in a Peru that differed in fundamental

ways from the Peru that he had left abruptly in 1968. The

final years of his presidency were marked by the rise of

Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) in 1980.

|

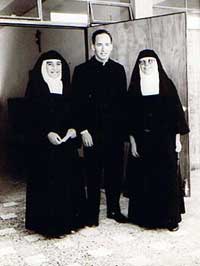

With Carmelite nuns at the

Cieneguilla language institute, 1964 |

The return

to constitutional rule was accompanied by the restoration of

formal democratic freedoms but this in itself could not create

a democratic society. The government showed no inclination to

reform powerful institutions which were suffused with

undemocratic practices and a traditional bias towards the rich

and powerful. Current affairs programmes on television that

were critical of the government had a checkered career,

several being removed from the screen by the television

companies themselves. During this period the radical

subversive group Sendero Luminoso, whose

ideological roots lay in a fundamentalist version of Maoism,

developed their guerrilla war.

By 1984

real income per capita had fallen back to the level of twenty

years before. While all but the small elite became poorer,

impoverishment was concentrated in the sierra and coastal

shanty towns. This has been a constant reality in Peruvian

history. Sendero Luminoso believed that the

conditions for revolution existed and that the road to

communism in Peru lay through 'a prolonged popular war'.

Another subversive but less radical group called the Tupac

Amaru Movement also initiated their military campaign in this

period. The government's initial response to Sendero

and to the Tupac Amaru Movement was to minimise the guerrilla

threat, but their counter-insurgency policy soon hardened as a

state of emergency was declared in five provinces, later to be

extended to many more, and the infamous island prison El

Frontón was reopened to hold Sendero suspects.

Sendero extended their campaign over a much wider area,

including the capital Lima. They destroyed pylons causing

regular blackouts in the entire city.

We were

living in Lima at that time. It was the first time I

experienced collective fear in the city in the midst of

blackouts, car bombs and selective assassinations. As popular

unrest and social upheaval increased, so did government

repression. Eventually Belaúnde handed over total

responsibility for counter-insurgency to the armed forces

chiefs-of-staff. This internal war was to continue until 2000,

throughout the governments of Fernando Belaúnde (1980-1985),

Alan Garcia (1985-1990) and Alberto Fujimori (1990-2000). More

than 69,000 people died or disappeared at the hands of

guerrilla groups, paramilitaries and the armed forces during

that internal war.

|

The author with his family

in

Bon Aire enroute to Peru, July 2006 |

A

family man

In the

midst of all these changes and upheavals my own life continued

to change. In 1990 I married a human rights lawyer called

Patricia Abozaglo from Lima. We met at my workplace. Our two

children Fiona and Patrick were born in Lima, Fiona in 1992

and Patrick in 1994. My work contract was coming to an end in

1995, so we decided to return to Ireland. Initially I was to

study for a year in post-graduate development studies in

Kimmage Manor, Dublin and at the same time to look around for

job options. Fortunately my wife got a job with Tróocaire right

away and I got a teaching job in a secondary school in Dublin

teaching Spanish, Irish and Religion. We had been in Dublin

for four years when we went searching for a house which

brought us to our present home in Maynooth, County Kildare,

just a forty- minute drive from my birthplace, Kilbeggan,

County Westmeath. So indeed I have come full circle. I am back

here, from where I set out for Peru some forty years ago.

Somewhat wiser I do believe. I am still teaching Spanish which

I enjoy greatly. I love introducing people to a new language

and opening up to them a whole new world of discovery.

Latin American connections

Since we

came back from Peru we have always kept in contact with

Peruvians and other Latin Americans who live in Ireland - and

there are quite a few. Over the years we have got together for

many parties, and now each July we have quite a gathering in

Dublin in Terenure College to celebrate Peru's national

holiday on 28 July. I suppose it is something like the

Westmeath/Longford Association that celebrates their

connection with Argentina every year.

Many years

ago I visited Argentina and spent a few days in Buenos Aires.

I stayed at the Passionist priests' house. I remember at meal

time hearing them switch back and forth in their conversation

between Spanish and English. There was an elderly priest

beside me and when he talked to me in English I could clearly

hear his Westmeath accent. He told me that his father - or was

it his grandfather - was from Moyvore in Westmeath. Another

memory I have with an Argentinean connection is meeting an

Argentinean priest in Cuzco years ago. He told me that his

parish was in the south of Argentina and that most of his

parishioners were of Irish descent. He told me how good they

were to him. He invited me to go and visit him and I must say

it is one of the regrets I have that I never did get to visit

him and meet all those Irish Argentineans and hear their

stories. So now you have my story, or at least a good part of

it.

Desmond

Kelleher |