|

The most significant reason for the minister's reluctance,

however, is revealed in the same letter, where Cooney stated

that most or all of the group were refugees because they were

Marxists, and that a significant proportion were 'activists.'

He feared that they would engage in political agitation soon

after their arrival in Ireland; 'they will not change their outlook on arrival in this

country.' [15] He suggested that such left-wing activists

would pose a far greater problem for Ireland

than for other Western European countries because of the

existence in Ireland of 'a relatively large and well-organised subversive group

towards whom such persons could be expected to gravitate.'

[16] Cooney proposed some form of screening programme to vet

potential refugees. [17] This forced migration of refugees

from Chile

to Ireland

was further complicated by Cooney's suggestion that some of

the refugees were in fact non-Chileans who had sought refuge

in Chile because it had a communist president. [18]

The Irish state played a minimal role in facilitating their

settlement in the country, and for security reasons, the event

received muted publicity due to the danger of releasing their

names to the Chilean media. The resettlement was privately

financed by the Committee for Chilean Refugees in Ireland and by religious groups.

[19] The Chileans who had arrived

seeking refuge in Ireland

were housed in local authority houses in Shannon, County Clare, and in Galway and

Waterford, and were allocated places on AnCo training schemes.

[20]

Many received training in metalwork. [21] After two

years, the Committee for Chilean Refugees in Ireland ceased to provide direct aid to the community, ostensibly to

promote personal autonomy. [22] It was only in 1977, three

years after the arrival of the group in Ireland, that

provisions were made for teaching the English language to

adult refugees, and even at that stage, only two hours'

tuition per week were provided. [23]

|

Protest against deportation by

Chilean refugees in Canada, 1998

(Gunther Gamper)

|

In response to a parliamentary question in early 1977, a

representative for the then Minister for Foreign Affairs,

Garret FitzGerald, stated that the minister 'maintained an

active interest in the welfare of the Chilean refugees in Ireland

and the efforts made on their behalf.' [24] At that time,

there were twenty-three Chilean heads of family living in Ireland; a total of ninety-four people. However, the representative

underlined the fact that the Department of Foreign Affairs was

not directly involved in providing assistance to the Chileans.

Local and national authorities were providing assistance to

the group and 'considerable progress has been made towards

their integration here.' Nevertheless, three years after their

arrival in Ireland, the Chileans who had settled in Galway

were reported to be experiencing continuing difficulties in

finding suitable employment. [25]

Little is known about the daily lives and achievements of the

group during their residence in Ireland. Some are known to have continued third-level studies at

Trinity College

in Dublin. [26] One Chilean refugee, Maite Deiber, whose husband had

been arrested and 'disappeared' during the unrest in Chile, went on to become conductor of the Trinity College Singers

in Dublin in 1978. [27] Very few of the 120 or so Chilean refugees who

arrived in Ireland in the early 1970s remain in the country. They experienced

serious difficulties in finding employment in Ireland due to a lack of targeted language or training programmes to

facilitate their integration into the labour market. [28] In

the late 1980s, the Chilean government announced an amnesty

for Chileans abroad who had been exiled by the coup, and many

of the refugees returned.

|

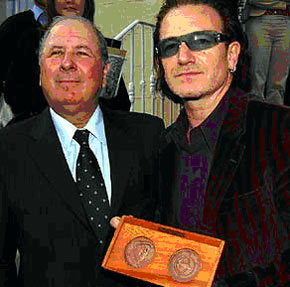

Chilean

Ambassador Alberto Yoacham presents the 'Pablo Neruda Medal

of Honour' to the Irish rock star Bono, for his contribution to music and humanitarian

causes,

23 September 2004

(AP photo/ John Cogill) |

Relations between Ireland

and Chile are naturally influenced by the activities of Irish migrants

in the region during the nineteenth century. While the most

significant migration of the twentieth century between the two

countries was the small-scale movement of programme refugees

between Santiago and Dublin during the 1970s, during the

twenty-first century Ireland is likely to be the destination

for many more Chilean immigrants. On being awarded an Honoris

Causa Doctorate by the University

of Chile

in 2004, the Irish President Mary McAleese commented on the

continuing potential for cooperation between the Republics of

Ireland and Chile:

No

es casual que Bernardo O'Higgins sea conocido como El Libertador. Estuvo entregado al espíritu de la libertad

iluminada. Es mi convencimiento que Irlanda [...] cuenta con

un socio legítimo en la República de Chile, con el cual

estamos destinados a trabajar más estrechamente a fin de

propagar aún más los frutos de ese espíritu de libertad a

lo largo de América Latina y el mundo. [29]

However, aside from the resettlement project in 1974, from

the 1960s to date, Irish governments have remained remarkably

silent in relation to dirty wars and 'disappearances' in Latin America, in contrast to many of the country's European neighbours.

Although many victims of forced disappearances in Chile

and Argentina had Irish names, - and therefore obvious Irish ancestry -

diplomatic and consular services consistently refused to get

involved. [30]

Most of the Chileans living in Ireland today are on short-term work permits or have married Irish

people and settled here. In 2002, there were a total of eight

Chileans working in Ireland on work permits and one Chilean architect on a work

authorisation issued by the Department of Enterprise, Trade

and Employment. By 2004, this number had increased to twenty

Chileans on permits and two professionals on authorisations,

and further increased to twenty-four Chileans working in Ireland

on work permits and one engineer on an authorisation in 2005.

In 2006, however, just five work permits for Chileans were

renewed, and six new permits and one authorisation were issued.

[31]

Trade between Ireland

and Chile has been growing significantly, and was valued at just under

€74 million in 2002, a fourfold increase since 1990.

Ireland

is represented in Chile

by an honorary consul, and general diplomatic representation

is handled by the Irish embassy in Argentina. The Embassy of Chile in

Ireland

opened on 1 July 2002, and in October of the same year, the first ever resident

Chilean ambassador in Dublin, Alberto Yoacham, presented his credentials to the President

of Ireland.

|

Romanian

refugees in Ireland, 2001

(http://www.cnn.com/SPECIALS/2001)

|

In the years that followed the settlement of the Chilean

refugees, many more people arrived in Ireland seeking refuge under UNHCR programmes, including Vietnamese

(1979-2000), Iranian (1985), Bosnian (1992-2000) and Kosovar

(1999) people in search of safety and freedom from

persecution. Ireland is one of only seventeen countries in the world with a

programme of refugee resettlement. In mid-2005, the Irish

Minister for Justice announced that Ireland was to significantly increase its annual refugee resettlement

quota from 10 cases - equating to about forty people - to 200

people per year. In light of the fact that Ireland recognised 966 asylum seekers as refugees and received about

70,000 immigrants during 2005 alone, [32] the resettlement

quota remains modest. The implementation of further increases,

however, seem likely, as Ireland continues to adapt and

develop its policies for the settlement of those who seek

refuge on the island.

The twentieth-century settlement of refugees, and indeed

other immigrants, in Ireland is a topic that has thus far received little attention in the

field of academic research. This is despite the implications

of Ireland's history of immigration for the future of the country. The

examination of the small-scale settlement of these South

Americans seeking refuge in the country may prove informative

with regard to future resettlement projects, and sheds light

on a little known connection between Ireland

and Chile.

Claire Healy

|